July 2016. I was back in southern Malawi as team leader for a small, biodiversity-related component of the Shire River Basin Management Program, a large project funded by the World Bank and implemented by the Government of Malawi’s Ministry of Water Development and Irrigation. Our work is supported by funds from the Global Environment Facility, and the activity is titled “Strengthening the Information Base of Natural Habitats, Biodiversity, and Environmental Services in the Shire River Basin.” We like to call it simply “natural habitats surveys.” It is being implemented under a contract to LTS International, a consulting firm based in Edinburgh, Scotland. These natural habitats surveys are meant to inform ecologically-sustainable development in the Shire River Basin, especially as related to land and water, and at the same time to safeguard Malawi’s biological diversity. I wrote about our work last year in two stories, “The View from Zomba Mountain,” and “Miombo Magic at Machinga Malawi.”

One of the objectives of our work is to provide management-relevant information about how to maintain or restore the natural woodlands and forests in the Shire River Basin. To do so, we needed to learn more about the regeneration potential of these ecosystems in the forest reserves that are supposed to protect many of the upper watersheds of the Shire, but which in many places have been disturbed and degraded by human activities, whether cutting for timber and building materials, charcoal-making, clearing for small scale farming, or hunting for bushmeat. That information would help us develop and communicate simple silvicultural and management “prescriptions” for regenerating more intact and productive woodlands at disturbed sites. Restoring such areas to a more balanced and resilient ecological condition will allow them to provide the full range of benefits they can produce, including their ecohydrological benefits in retaining rainfall, increasing infiltration and groundwater recharge, and reducing runoff, flooding, soil erosion, and sedimentation.

My Malawian colleague and Deputy Team Leader, Daulos Mauambeta, and I met with staff from the Forest Research Institute of Malawi – usually called by its acronym “FRIM” – on a warm Monday afternoon in late July, to discuss and plan our study of regeneration potential. We settled on a method for measuring regeneration potential that is part of the standard forest inventory methodology they have been using recently in three forest reserves in Malawi, including the Liwonde Forest Reserve, one of the sites of our natural habitats surveys.

——-

Three days later we were on our way to field-test the methodology on the slopes of Chikala Hill, a peak on the eastern end of the Liwonde Forest Reserve. We drove north from Zomba on a sunny morning, through Sangani and along the east side of the Zomba-Malosa Forest Reserve, its high ridge fading into the smoke haze from dry-season field burning. We reached the police post below Chikala Hill at about 11 AM, parked in the shade of a big mango tree, and headed uphill, through the village mango shade, foraging chickens and goats, and gaggles of curious children. At the edge of the village we passed through a fringe of regenerating woodland, and finally into less-disturbed, taller and shadier woodland, climbing on a steep and rocky local path. There was a slight breeze, but the day was quickly getting hot. Something I ate the day before had disturbed my intestinal ecosystem, testing its regeneration potential, and I didn’t have my usual energy.

As we climbed we had a tutorial in how the local community uses the woodland and forest here. We passed people descending with examples of the products they harvest for free in this forest reserve: men with long bundles of thatching grass, or hoe handles cut from the base of several species of trees where the root bends and sends out a straight upward shoot; women with bundles of firewood on their heads bigger than they were; other men with rough-cut planks destined for doors, windowframes, or furniture. In a few places along the trail we saw where traditional healers had dug for medicinal roots, or stripped sections of bark from trees that were part of the indigenous pharmacopeia.

After two hours we finally reached the site of one of the rapid botanical surveys we did last year; the forested peak of Chikala Hill loomed above us. We took a short break, and then started to work.

To gather information about regeneration potential at a site to be sampled – sites where the rapid botanical assessments we conducted last year showed a degradation of forest cover from human activities, but nevertheless a full complement of plant species that would be found in more intact habitats – two types of information were recorded. First, a circular “microplot” with a radius of two meters was marked out, and all the little seedling trees in that circle, by species, were recorded in three different size classes – call them small, medium, and person-height. Then all of the bigger, mature trees in a larger area surrounding the microplot were listed, by species and size. If the species composition of the seedlings doesn’t match that of the bigger trees, it may indicate that some tree species have been harvested when they get bigger – for building materials or charcoal-making, for example – even though their offspring may still survive as seedlings at the site. In order to regenerate the natural woodland, it may be necessary to preserve some large, mature individuals of every species to provide a seed source for regeneration. A few hours later, having collected this information and successfully tested the methodology, we hiked back to our car parked under the mango tree, tired and hot, and returned to Zomba in the late afternoon.

——-

The study of regeneration potential was only one of half a dozen studies we did this year. Another was a survey of birds at the sites where we had conducted rapid botanical surveys last year. Those botanical surveys gave us a picture of the plant species composition of the woodlands and forests at a wide range of sites in the Shire Basin, and also identified any globally rare or endemic plants that were found there. The bird surveys were conducted by Tiwonge Gawa, an ornithologist and expert on Malawian birds who works for the National Museums of Malawi.

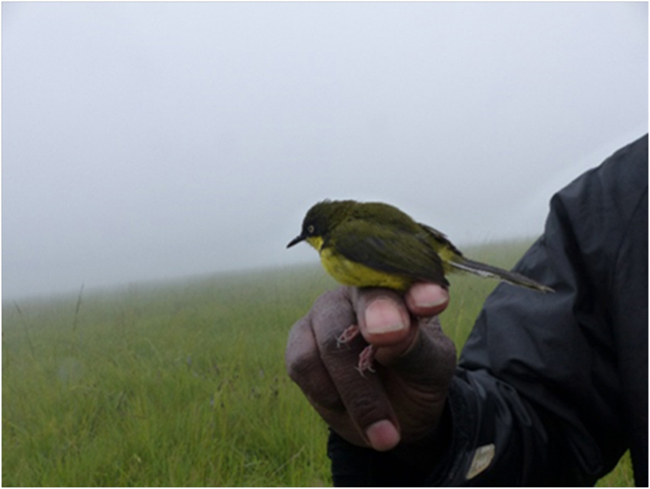

Last year I wrote about testing our rapid botanical survey methodology in the Afromontane forest on Zomba Mountain. The Zomba forests, and those on the peaks of the adjacent Malosa Forest Reserve, are the habitat of Malawi’s only endemic bird species, the Yellow-throated Apalis, Apalis flavigularis. An “endemic” species is one with a restricted range, found nowhere else. The Yellow-throated Apalis is considered an endangered species due to the small population that its limited habitat can support. If the montane forests of Zomba and Malosa are degraded, the species won’t survive. The Yellow-throated Apalis is therefore an “indicator species” of the condition of the forests it inhabits.

Another indicator species for the intactness and health of Afromontane moist forests at the sites we surveyed is the Thyolo Alethe, Alethe choloensi. It is also considered endangered because of its small range and population size. Miombo woodlands, which cover the largest part of the forest reserves below the highest peaks with their montane forests, also have a suite of specialist bird species that can serve as indicator species, such as Steirling’s Woodpecker (Dendropicos steirlingi) and the Olive-headed Weaver (Ploceus olivaceiceps).

The montane forests that cover the highest elevations of the Mangochi, Liwonde, and Zomba-Malosa Forest Reserves are the tops of the watersheds that feed rainfall – which is much higher on these mountains than at lower elevations – to the Shire River. As such, they provide important ecohydrological services. In my story “The View from Zomba Mountain” I summarized the scientific evidence that species diversity in an ecosystem is related to its ecological functioning, and that in turn is related to its ability to provide ecosystem services and other benefits that people depend on. In her report on the bird surveys, Tiwonge Gawa wrote: “It is therefore important that the unique biodiversity that makes up these forests remains in its most natural form to ensure the continuation of the ecosystem services provided. Monitoring the presence and populations of some of the Afromontane endemic species is one way of checking the health of this habitat.” In other words, the presence and population size of the Yellow-throated Apalis and Thyolo Alethe, adapted as they are to the characteristics of those forests through their long evolutionary history, can indicate subtle aspects of the condition and functioning of the forests that we could not otherwise understand or measure.

——-

We also conducted butterfly surveys at the sites of our rapid botanical assessments from last year. The butterfly surveys were done by Steve Collins, of the African Butterfly Research Institute (ABRI), based in Nairobi, Kenya. ABRI is the world center of knowledge and research on African butterflies. Steve mounted a butterfly research expedition that reached many of the highest summits in the forest reserves of the Shire River Basin, including Chikala Hill, Mangochi Mountain, and the peaks of the Zomba-Malosa Forest Reserve. These peaks and high ridges are covered in Afromontane evergreen moist forest. Steve’s report noted that “The evergreen forest patch on the top of Chikala Hill is one of the most intact evergreen forests in Southern Malawi.” It is only about 300 hectares in area, a tiny remnant of what once existed.

Steve was especially interested in one group of butterflies he called the “Mountain Dotted-border Whites.” They belong to a species group that includes a butterfly with the scientific name Mylothris sagala. On Mangochi Mountain, Steve found a butterfly similar to Mylothris sagala, but different enough that he says it is a new species, not known or described scientifically before. On Chikala Hill he found similar butterflies that he thinks must be closely related to those on Mangochi Mountain. The evolutionary-genetic relationship between these butterflies, and others in the Mylothris sagala group, is now being studied by specialists as part of a taxonomic revision of the genus Mylothris. According to Steve, when the taxonomy is clear his study may have identified one or two new species. He suggested that if the populations on Mangochi Mountain and Chikala Hill turn out to be one species, a suitable name could be Mylothris shireensis – whose common name could be the “Shire Mountains Dotted-border White.” I would consider it quite a coup if Steve’s work identified the “flagship” species for the Shire River Basin Management Program: a tiny butterfly, a new species, the Shire Mountains Dotted-border White, found nowhere on Earth except the tops of the mountain ridges and hills that capture the rain that nourishes the Shire River.

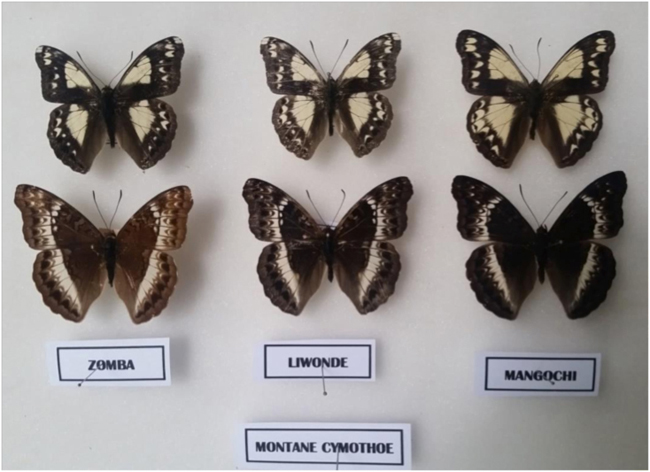

Mylothris sagala group, showing potentially new species from Mangochi Mountain (top) and Chikala Hill (middle)

Another group of butterflies Steve’s survey looked at was what he calls the “Montane Cymothoe Group” – he also calls this group “Gliders,” I suppose describing their pattern of flight. Butterflies in the genus Cymothoe are found on all of what are called the “Eastern Arc” mountains of East Africa, from the Taita Hills of southern Kenya to the Vumba Mountains in eastern Zimbabwe. They have genetically diverged and speciated in patches of montane evergreen forest that became isolated “islands” in a “sea” of drier and warmer ecosystems over millions of years of natural climate change. According to Steve, if their larval food plants – trees in the genera Dasylepis or Rawsonia are present, there is a high probability that the butterflies will be there. Cymothoe zombana – the Zomba Glider – was only known from Zomba Mountain, but in his survey Steve also found it along the mountain ridge farther north on Malosa Mountain, and also on the top of Chikala Hill in the Liwonde Forest Reserve. The population from Mangochi Mountain, farther north, is a new species, not collected or described scientifically before. DNA analysis confirmed that it is not the same as three other species found in Malawi: C. mulanjae on Mt. Mulanje, C. zombana found in Zomba-Malosa and on Chikala Hill, and C. cottrelli, found on the Nyika Plateau.

Both of these groups of butterfly species, the Mylothris and Cymothoe species groups, are indicators for the quality of the forests they inhabit. They are found only in Afromontane forest that is intact and not degraded. Their larval food plants, species of Rawsonia and Dasylepsis, are large, slow-growing trees, and because they are hardwoods, they are sought after for timber. If these trees have all been cut, there will be no larval food plants for these butterflies.

——-

Coincidentally, as I was travelling to and from Malawi, I was also reading a book of old essays by Aldo Leopold, a pioneering American forester, conservationist, and ecological philosopher. The book, The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays by Aldo Leopold, edited by Susan Flader and J. Baird Callicott, presents a chronological history of the evolution of Leopold’s ideas through both published and unpublished essays spanning his adult life from 1904 to 1947. I wrote about Leopold in July of this year, after visiting “The Shack,” the rustic nature retreat that inspired his short book of essays A Sand County Almanac, for which he is best known.

One thing is clear from reading The River of the Mother of God – Leopold was decades and decades ahead of his time in the sophistication of his thinking about the human-nature relationship. To me, some of the ideas expressed in his essays starting in the early 1920s and continuing through the late 1930s are at a level of insight that we have barely caught up with now. They are nothing less than brilliant.

As I read, I found his ideas resonating with my impressions of our work in Malawi. Why? In some of the essays in The River of the Mother of God Leopold begins to explore the idea of species that represent or symbolize the “wholeness” or “intactness” of an ecosystem.

This idea is central to his essay “Guacamaya,” for example, published in A Sand County Almanac with Essays on Conservation from Round River. Guacamaya is the common Spanish name for the Thick-billed Parrot (Rhynchopsitta pachyrhyncha), which Leopold encountered on one of his trips to Chihuahua, Mexico. This passage from that essay conveys the idea: “Everybody knows, for example, that the autumn landscape in the north woods is the land, plus a red maple, plus a ruffed grouse. In terms of conventional physics, the grouse represents only a millionth of either the mass or the energy of an acre. Yet subtract the grouse and the whole thing is dead. An enormous amount of some kind of motive power has been lost. It is easy to say that the loss is all in our mind’s eye, but is there any sober ecologist who will agree? He knows full well that there has been an ecological death, the significance of which is inexpressible in terms of contemporary science. A philosopher has called this imponderable essence the numenon of material things. It stands in contradistinction to phenomenon, which is ponderable and predictable, even to the tossings and turnings of the remotest star. The grouse is the numenon of the north woods, the blue jay of the hickory groves, the whisky-jack of the muskegs, the piñonero of the juniper foothills. Ornithological texts do not record these facts. I suppose they are new to science, however obvious to the discerning scientist.”

The “philosopher” to whom Leopold was referring in that passage was the Russian mystic-philosopher Piotr Ouspensky, whose book Tertium Organum was translated into English in 1920, and immediately generated a “buzz” in America philosophical circles, according to Curt Meine, a Leopold biographer. It attempted to reconcile Western science and Eastern mysticism in a kind of holistic, “systems” worldview that had similarities to the ideas of Alexander von Humboldt. “Ouspensky’s animism challenged Newtonian mechanics and the Cartesian view of nature; it accepted the latest advances in physics and evolutionary biology as further proof of the indivisibility of the cosmos,” Meine explained. Ouspensky’s ideas resonated with Leopold, who read Tertium Organum in the early 1920s. According to Flader and Callicott, writing in the Introduction to The River of the Mother of God, “Leopold adapted the concept of noumena from Ouspensky and used it to designate the vital signs, so to speak, of the health of land organisms, species without which ecosystems would lack wholeness and integrity.”

Leopold saw these numenous, indicator species not only in an ecological but also in an evolutionary sense, as is clear from the description of sandhill cranes in his essay “Marshland Elegy” in A Sand County Almanac. “Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins, as in art, with the pretty. It expands through successive stages of the beautiful to values as yet uncaptured by language. The quality of cranes lies, I think, in this higher gamut, as yet beyond the reach of words. This much, though, can be said: our appreciation of the crane grows with the slow unraveling of earthly history. His tribe, we now know, stems out of the remote Eocene. The other members of the fauna in which he originated are long since entombed within the hills. When we hear his call we hear no mere bird. We hear the trumpet in the orchestra of evolution. He is the symbol of our untamable past, of that incredible sweep of millennia which underlies and conditions the daily affairs of birds and men. And so they live and have their being—these cranes—not in the constricted present, but in the wider reaches of evolutionary time.”

But alongside his arguments for the value of numenous species, Leopold also made an equally strong utilitarian argument for conserving all species. This was clear from his “first rule of intelligent tinkering” analogy. So, while he said that the value of cranes was mysterious and “beyond the reach of words,” he would have been as quick to argue that without cranes, and crane marshes, the watersheds of North America were at risk of losing their ability to provide the ecosystem services – a term that was coined only much later, but which Leopold fully understood – that millions of people depend on.

——-

The Yellow-throated Apalis and Thyolo Alethe are the noumena – the eco-evolutionary indicator species – for the health and quality of the mountaintop forests of Zomba Mountain or Chikala Hill. So are the Shire Mountains Dotted-border White, and the Mangochi Mountain Glider, butterfly species new to science, which reflect a deep ecological and evolutionary relationship with their unique, restricted mountaintop forest habitats. These noumenous birds and butterflies are the indicator species for the health and quality of the natural forest ecosystems that provide irreplaceable ecosystem services – stable flows of water from the mountain watersheds of the Shire River Basin – to the millions of Malawians who depend on that water for domestic uses, sanitation, agriculture, energy, and industries.

For related stories see:

- Morning Visit with Aldo Leopold at the Shack. August 2016.

- Sugar Maples, Climate Change, and Ecohydrology in the Sierra de las Minas of Guatemala. February 2016.

- Butterflies in a Blizzard, or Chaos in Colorado and What It Means for Us. January 2016.

- Miombo Magic at Machinga Malawi. June 2015.

- The View from Zomba Mountain: Plants, Water, and People in Southern Malawi. June 2015.

- Islands of Biodiversity in the African Sky: Golden Monkeys and Irish Potatoes. September 2014.

- Searching for Grauer’s Swamp Warbler at the Top of the Nile. September 2014.

- Ecohydrology of the Honduran Highlands. September 2013.

- A Sunday Cerro Guanacaure, Honduras. August 2013.

- Islands of Biodiversity in the African Sky – the Nyika Plateau. April 2013.

- Islands of Biodiversity in the African Sky – Mulanje Mountain. April 2013.

- Tanzania’s Usambara Mountains and Kilombero Wetlands. June 2012.

Sources and related links:

- Shire River Basin Management Program

- LTS International

- Strengthening the Information Base of Natural Habitats, Biodiversity and Environmental Services in the Shire Basin: Year 1 Analytical Report. February 2016.

- River of the Mother of God and Other Essays by Aldo Leopold. Susan Flader and J. Baird Callicott, eds. 1991. U. of Wisconsin Press.

- A Sand County Almanac with Essays on Conservation from Round River. 1949. Random House, Inc.

- Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work. Curt Meine. 2010. U. of Wisconsin Press.

- Marshland Elegy pdf