August 2023. In my last story, I wrote about revisiting the tidepool at Middle Cove of Cape Arago on the central Oregon coast where I’d done some of my doctoral research. On that trip I also went back to another significant place at Cape Arago that I call “Poetry Cove.” Here’s the background:

During my second year of college I was casting about for a job for the coming summer, and wrote Bill Arbus, the director of Camp Arago, about being a counsellor for him. I’d been a “camper” at that marine science camp, which was sponsored by the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in Portland, during the summer after my sophomore year in high school. I’d learned about it through relatives in Portland. Bill was eager to hire me; he knew he could pay me practically nothing and have me pour my heart and soul into his camp enterprise, on duty 24/7, because of my passion for tidepools. Camp Arago became my summer “job” for the next five years.

We were a small group of counsellors—most of us students in college or grad school trying to connect our studies and our passions. The campers were a rowdy mix of Oregon kids who were there mainly because their parents thought an OMSI science camp sounded more educational than your usual horseback-riding-and-crafts camp. Among the counsellors there was Dave, the geologist; Tom and Elaine, fellow biologists; a bunch of enthusiastic junior counsellors; and Ed, nicknamed “Shorty” because he was 6’4”, the camp’s maintenance wizard and all-purpose problem-solver. And Esther, the cook, the mastermind of comfort that poured from the kitchen three-and-a-half meals a day—never more blessedly than the “oh-dark-thirty,” pre-low-tide-trip snack of fresh-baked cinnamon rolls, hot cocoa, and scalding coffee. I bless you to this day, Esther! We were usually off before dawn on the bus to Cape Arago to catch the lowest of low tides of each monthly tide cycle.

Bill had developed a set of standard “field labs” that filled the mornings and afternoons after the early tidepool trips and before the pre-dinner volleyball games and after-dinner sing-along campfires. One went to the Charleston Boat Basin to look under the docks at the amazing sea life attached there; another went to a bog to find insectivorous cobra plants; and another to Fossil Point to look at local geology. But he also invited all of the counsellors to innovate, and develop our own field labs. I invented one called “Waves and Beaches,” based on my fascination with an old book by Willard Bascom with that title about that subject. The campers and I threw grapefruits (which float and are yellow and easy to spot) into the surf at Bastendorff Beach and watched where and when they washed in to detect longshore currents. We timed the breaking waves with stopwatches and recorded the times, looking for the “beat frequencies” that created extra-big “sleeper” waves, and we imagined some of those waves being born in a big storm off Bora Bora or somewhere far across the Pacific. Sure enough, we found beat patterns in the breakers, as Bascom and the science of surf said we would, along with longshore currents, rip currents, and rip channels. And then we lounged on the sand in the sun until it was time for the bus to pick us up to return to camp.

I also invented a field lab that was a bit unusual for a science camp, I suppose. I called it “Poetry Cove.” That came about for a couple of reasons. One was that during my senior year in high school I took a class called only, as I recall, “Humanities.” Among many eclectic, cross-cultural explorations in that class, Mrs. Mendius had us read and write haiku poetry. Something about the sparse imagism and humility of haiku resonated strongly with me. She submitted some of our class’s work to a National Scholastic Magazine competition, and one of my haiku was selected and published that year. My winning entry was:

On morning sidewalks

last night’s rain recorded in

pink earthworm cursive.

The image I tried to capture is still fresh in my mind today. Our paper boy (yes, a boy who rode his bicycle up and down the street every morning delivering the paper) always threw the paper at the bottom of our driveway, and one early summer morning when I went out to get it, after a nice rain at night, the worms had come up out of their flooded burrows in our lawn and were squiggling across the sidewalk leaving wet trails, trying to get back underground before they dried into brown spaghetti.

The second bit of my karma that led to the invention of the Poetry Cove field lab was that in order to avoid taking the regular required Freshman English class in college, I had applied to pass into a poetry class by submitting some poems, including a few haiku. A dozen of us were allowed to ditch Freshman English, and instead read imagist poems with a young professor in the English Department, Diane Middlebrook, a noted biographer and a poet herself. Professor Middlebrook had us reading William Carlos Williams, Theodore Roethke, William Stafford, Louise Bogan, and lots of other challenging recent poets, and then trying our hand at emulating them. It was great fun, as I recall.

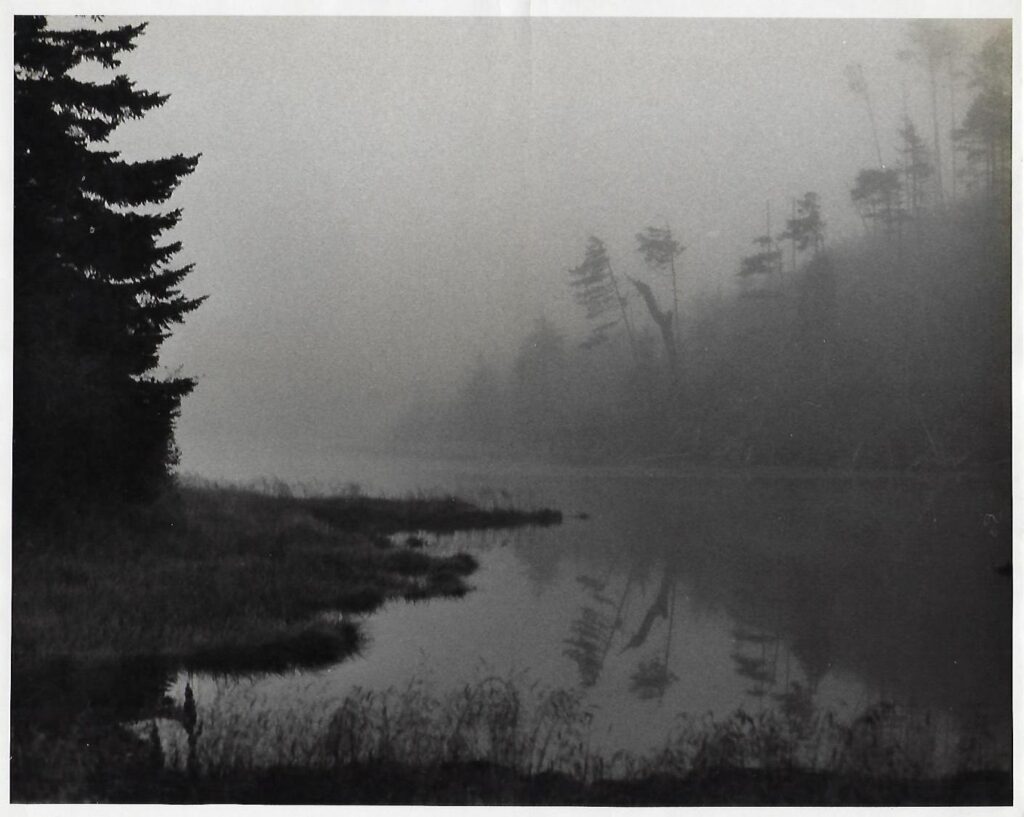

So, when I found myself a counsellor at Camp Arago, I figured: poetry and marine biology are close relatives, at least to me! So maybe kids would like to hike into the most beautiful, intimate, hard-to-get-to cove on all of Cape Arago, sit around all afternoon in the sun, and write imagist poems. Bill Arbus gave me the green light, and the Poetry Cove field lab was born.

After scrambling down a sandy gully, grabbing the roots of a big Sitka spruce that was being undercut by erosion to slow our slide, we dropped into the cove. Getting there was half the fun. The assignment was to wander around or sit on a log or rock, looking, listening, observing openly, until some image from the place came into mind, and then write down some words to capture all that. If you were quick and inspired, there might be time for a quick dip in the cold ocean if the tide was up in the cove and a bake on the warm sand to warm up. After an hour and a half of sitting, experiencing, and writing, everyone, including me, had to share their “poem” with the group. The campers seemed to love it, and the lab lasted year after year, becoming a tradition.

_______

The Poetry Cove field lab was an expression of my conviction that there is no real difference between the fundamental activity of science and of art: observation. Pure, unadulterated observation, using all the senses to get an image of the world “out there,” and then recording it in some manner. Capturing it in words, or data, so it is not only accessible to the observer again, but to other people as well, and so that the listeners or readers can share and confirm the observation. And here’s the thing that some “scientists” who have been over-trained in the Western, rationalist tradition of reductionist science don’t get: so that they can share the feeling, the emotion, the delight of the real world they are embedded in. Poetry Cove was an expression of my feeling that the aesthetic and even spiritual aspects of nature aren’t in a different realm from the rational, scientific aspects.

My poems have always been “ecological.” Trying, that is, to express interconnectedness, the fundamental principle of ecology. A Chilean friend calls me “biopoeta,” and I love that appellation in Spanish. And my scientific studies have always had, I think, an aesthetic quality. Maybe that is why so many of them have involved cryptic coloration, camouflage, and behavior—all of which deal with colors and patterns, the perceptions of them by our own or their predator species, and the reasons for them.

_______

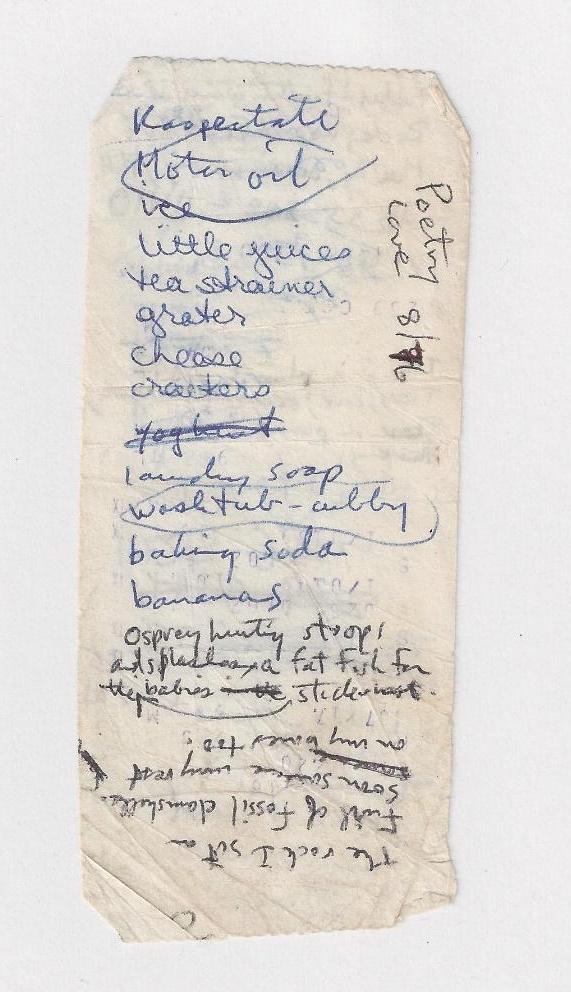

I’d sometimes forget to bring a notebook to Poetry Cove, but could usually find some scrap of paper in my wallet or knapsack to scribble my poems on. A few years ago I found some of those now-yellowed scribble-scraps among my Camp Arago memorabilia. My favorite is a supplies list (groceries and more) from 1976, with two poems squeezed on at the bottom, one right-side up, one upside down.

Osprey hunting stoops

and splashes, a fat fish for

the sticknest babies

The rock I sit on

full of fossil clamshells.

Soon someone may rest

on my bones too.

The other side of the list had two more poems, plus the phone number of Esther Dixon, the camp cook, and Bill Arbus’s address and phone number.

Folded & faulted waves

of rock, old Earth still moving,

ocean moving, still.

This is a planet!

Trees. cove, ocean, and my thoughts

are a planet too!

_______

I mentioned at the beginning that one reason for my recent Oregon trip was a reunion of the old Camp Arago staff. Tom had lined up a rental house, perched above Joe Ney Slough a southern arm of Coos Bay, just down from the old camp property, where the dozen or so of us could gather to eat, drink, and reminisce. At one of our gatherings, someone (not me) proposed that we should each write a haiku and share it on the last evening… I smiled. The Poetry Cove tradition lives on!

This was my entry:

Joe Ney Slough evening

the tide rising or falling

some things never change

_______

For related stories see:

October 6, 2023 11:42 pm

Bruce, I love this! You nailed it! Both your description and the photos combine to capture the feeling of the experience. Thank you.

October 7, 2023 4:13 pm

Thanks, Tom, glad this resonated with you! That’s high praise coming from a fellow Arago counsellor!

October 7, 2023 2:47 am

Thank you Bruce for sharing these memories of my childhood, stories about my parents and reminding us all that art and science are dimensions of the other.

October 7, 2023 4:17 pm

Thanks for the feedback, Charon. The memories are still strong from Arago days for many of us.