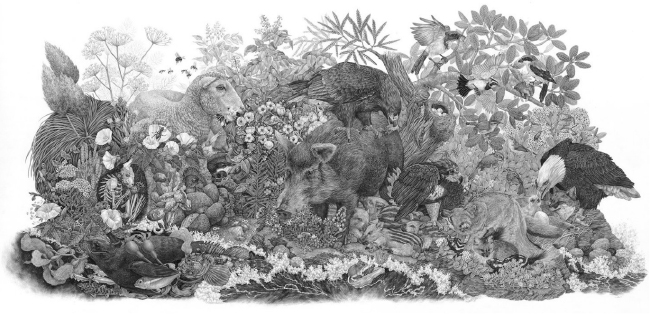

The large fabric print hanging on the west wall of the dining room of the Santa Cruz Island Reserve research station caught my eye immediately. A tangle of creatures drawn in detailed black covered the white background, intertwining in almost Escher-like fashion. There were sheep and foxes, eagles and jays, oaks and mallows, skunks and abalone, and as I got closer and began to really see the detail, my head was spinning. What was this piece, and who had done it?

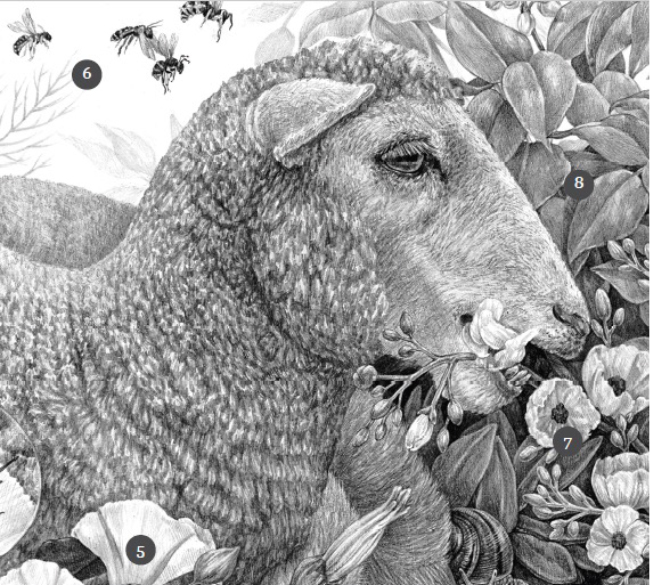

After some quick inquiries and online searching, the story of this ecological art emerged. Titled Limuw | Santa Cruz Island, this pencil drawing by Zoe Keller is seven-and-a-half feet wide and four feet tall and includes over 60 species found on Santa Cruz Island. Why does this deserve to be called “ecological art,” rather than just nature art or scientific illustration? Because Keller is ambitiously telling an ecological story here, not just using plants and animals as pretty subjects. As you move across the drawing from left to right, species that were important to the former native inhabitants of the island, the Chumash, are shown; then we see the gradual mixing in of the non-native species introduced by Euro-Americans and their ecological effects on the unique biodiversity of the island. This is a tour-de-force of ecological art.

I have long been interested in the relationship between art and ecology, for several reasons. One is that I’m convinced that the observational and intuitive psychological processes of artists and scientists are very similar. I have always resisted the old “two cultures” narrative that suggested that science and art exist in two different psychological worlds, two parallel universes. Since I’ve always lived in a world that values each, I’ve struggled to explain my view to the “two-culturists” who are still common among us. I tried to do so in an essay in my book about the Cascade Head Biosphere Reserve on the Oregon coast, which was catalyzed by a four-month residency at the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology. The Sitka Center’s name seems to imply a one-culture view, but it sometimes still struggles to overcome two-culturism. That essay described my conversations with a biological artist, Nora Sherwood, who ended up illustrating the book with a wonderful frontispiece and chapter-heading sketches. I’ve found support for my unified art-and-ecology view from historical research on the founders of American environmentalism. They were searching, beginning in the 19th century, for a new worldview that blended science with aesthetics; Alexander von Humboldt is a founder of the trend, but essayists like Emerson and Thoreau and painters like Cole and Church took up the torch, and passed it on to writers like Muir and Leopold.

What a story Zoe Keller’s ambitious work tries to capture in a visual canvas of only seven-and-a-half by four feet! Indigenous Americans lived on Santa Cruz Island for more than 13,000 years; the name in the language of the most recent of them, the Chumash, is “Limuw.” We don’t actually know when they first arrived, but a human skeleton from neighboring Santa Rosa Island dated to 13,100 years ago. They must have come by boat, because even then, at the end of the last glacial maximum when sea level was hundreds of feet lower, the Channel Islands were still a few miles from the mainland of what would come to be called “California” much later by the Spanish.

_______

This essay concerns the ongoing story of the efforts to undo the ecological impacts from more than 150 years of assault by introduced European livestock—sheep, pigs, cattle, and horses—on an island with no native large herbivorous mammals. By the early 2000s, nine species of plants and one animal, the island fox, were listed under the Endangered Species Act as either threatened or endangered. Several decades of efforts to restored the damage done to the Santa Cruz Island ecosystem have produced some rapid and remarkable success stories, but also highlight ongoing challenges. Biosphere reserves in UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Programme network are meant to be laboratories for learning lessons about how to heal the human-nature relationship, and perhaps models to be emulated and replicated elsewhere. Santa Cruz Island, as a core site in one of those, the Channel Islands Biosphere Reserve, is a rich and fascinating example. Before summarizing some successes and remaining challenges, we need to set the stage with a summary of the history of people and nature here.

By 1800, more than 250 years since their first encounter with Spanish explorers, the indigenous Chumash population on the island had been devastated by introduced European diseases, and the last inhabitants were removed from Limuw by 1814 and taken to the San Buenaventura and Santa Barbara missions on the mainland. In 1839, the entire island was given as a land grant by the Mexican government to an army captain, Andres Castillero, who began ranching operations there; by 1853, historical records document large numbers of sheep, pigs, and horses on the island. Castillero sold the island to American investors in 1857, and by the time of the Civil War, which increased the demand for wool, 24,000 sheep roamed the island, and it was known for the quality of the wool produced there. In 1869 the island was sold again, to a group of San Francisco investors. By 1880, one of them, French immigrant Justinian Caire, had become the sole owner. Caire expanded ranching operations, planted vineyards and fruit and nut orchards, and introduced European honey bees to pollinate the orchards and vineyards and to produce honey. He also brought in other non-native species such as Australian eucalyptus trees and European sweet fennel. The fennel soon became naturalized and spread, and now dominates large areas on the island, overwhelming native vegetation. By 1890 there were more than 50,000 sheep on the island. Wine and wool were the main products of Caire’s Santa Cruz Island Company, and it produced what was reputed to be one of the best Zinfandel vintages in California at that time, until Prohibition closed the winemaking operation in 1920.

In 1937, Caire’s descendants sold 90 percent of the island to Los Angeles oilman Edwin Stanton, who soon switched the ranching program from sheep to beef cattle. When he died in 1964, his son Carey, a physician, moved to the island and continued the cattle ranching operation. Both the elder and younger Stanton recognized the geological, ecological, and anthropological uniqueness and importance of the island, and welcomed scientists. Carey Stanton began his relationship with the University of California-Santa Barbara in 1964, when a summer field geology class was held on the island for the first time; by 1966 a rudimentary field station of what would become the Santa Cruz Island Reserve was established. In order to protect the island from future development, Dr. Stanton sold his part of the island to The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in 1978 for a fraction of its market value, and TNC’s Santa Cruz Island Preserve was established. In 1980, Channel Islands National Park expanded the Channel Islands National Monument (established in 1938 by Franklin D. Roosevelt, which then included only Anacapa and Santa Barbara Islands) to include Santa Cruz Island, and its northern siblings, Santa Rosa and San Miguel Islands. Although Santa Cruz Island is included within the boundaries of Channel Islands National Park, TNC’s portion of the island—the western 76 percent—does not belong to the National Park Service. Today, the national park, TNC, UCSB’s Santa Cruz Island Reserve, and the Santa Cruz Island Foundation all work together to protect the island’s natural, cultural, and historic resources. The Santa Cruz Island Reserve continues to provide facilities and access to the island for education and research through an agreement with TNC.

_______

I love hollyhocks, especially the pink ones. That’s because of their emotional connection with New Mexico for me. Pink hollyhocks leaned over fences around old adobe houses in Santa Fe, grew in my mom’s garden in Los Alamos, and embedded themselves in my memory of delight. Hollyhocks are members of the plant family Malvaceae, whose unique pinks carry throughout the blossoms of the family. So when I first saw a photo of the federally endangered Santa Cruz Island bush mallow (Malacothamnus fasciculatus var. nesioticus), how could I not be enamored with it?

Karen, Don, and Steve, plant-restoration specialists who have worked for decades to restore this endemic species to the island through their non-profit organization, Growing Solutions, had arrived at the field station midway through our week there for an end-of-season monitoring visit. By this time of year, the bush mallows were going into dormancy, so I didn’t get to see their seductive pink blossoms.

The island bush mallow is “a long-lived, clonal shrub” (McEachern et al., 2010, p. 16) that “reproduces vegetatively by rhizomes, the primary means of establishment and persistence in natural populations” (Wilken and McEachern, 2011, p. 410). In less technical words, a bush mallow can send out roots, which can then send up new shoots away from the mother plant, but those shoots are genetically the same as—clones of, that is—their mother plant. The bush mallow is typically found in island chaparral vegetation, growing among other chaparral species like island scrub oak (Quercus pacifica) and manzanitas. As I discussed in my previous story, chaparral is a fire-adapted plant community, and the bush mallow’s mode of vegetative reproduction fits right in as a strategy for surviving periodic fires.

The Santa Cruz Island bush mallow was first described scientifically in 1886. In the late 1990s, after more than a century of overgrazing by sheep and cattle, erosion and soil loss from rooting by wild pigs, suppression of fires, and other habitat alteration, a search for the last survivors was mounted. According to Karen, Don, and Steve, they finally found a thriving plant among the splintered boards of the old outhouse that had blown down long ago at the Christy Ranch on the western end of the island, where the last bush mallows had been reported by botanists in 1927 and 1930. Apparently the sharp, splintered lumber of the outhouse, like a fence of archer’s stakes on a medieval battlefield, saved that single plant from the sheep and cattle that had grazed there until the late 1970s. The outhouse was on top of a narrow rocky ridge, “a weird spot for outhouses, but it certainly had outstanding views of the coastline and beach,” Karen recalled.

When it was federally listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1997, further surveys had found more plants at Christy Ranch, and a small population on a steep, south-facing slope near the UCSB field station. Only 42 plants were counted in these two widely separated populations. An ESA recovery plan for the species “called for studies of life history and seed germination, development of propagation protocols and outplanting techniques, and subsequent establishment of viable populations” (Wilken and McEachern, 2011, p. 410). Two additional surviving populations were discovered through surveys after ESA listing, one on the south side of the island, and one that appeared on Cebada Ridge near the Christy Ranch after a controlled burn in 2000, a nice demonstration of the fire-following nature of the island bush mallow (McEachern et al., 2010, p. 16). This population probably resprouted from long-suppressed underground roots, or perhaps even grew from seeds that had been waiting in the soil “seed bank” for release by the heat of a fire or leachate from charcoal from the fire, both known to stimulate germination in other chaparral species.

To implement the ESA recovery plan, Karen, Don, Steve, and volunteers from Growing Solutions located plants in the surviving populations, took cuttings from them, and propagated over 500 plants in a nursery-like shade structure not far from the research station beginning in 2011. In 2016, these nursery-raised plants were planted out at suitable sites across the island and were reported to be surviving and sending out roots that would eventually give rise to new plants. It was these outplantings that Karen, Don, and Steve were here to monitor when our visits to the island overlapped.

Studies have shown that Malacothamnus fasciculatus var. nesioticus is genetically distinct from the other, mainland subspecies of bush mallow. That research has also shown that it has low levels of genetic variability (Wilken and McEachern, 2011, p. 411), which could potentially harm its adaptive potential and long-term survival. Two things could explain its low levels of genetic diversity. One is that small populations retain less diversity than larger populations—and the island bush mallow has certainly experienced what biologists call a population “bottleneck” because of its small numbers. The other explanation might be the lack of genetic mixing through sexual reproduction (pollen, seeds, etc.) and the predominance of vegetative reproduction in widely separated populations—widely separated now, at least, by their devastation by the hungry mouths of sheep and cattle, but probably much more contiguous in the pre-European, pre-grazing past.

The island bush mallow can reproduce sexually through seed production; it is even “self-compatible,” meaning that flowers from a single plant can produce viable seeds, although that requires visits by pollinating insects. Research on Santa Cruz Island by entomologist Dr. Robbin Thorp of the University of California-Davis reported few native bush mallow pollinators, and “therefore, pollinator limitation may be a factor in poor seed set at one or more sites” (McEachern et al., 2010, p. 17). Hand pollination—mimicking natural insect pollination by using tiny paintbrushes to move pollen from one flower to another—was shown to increase seed production, but this attempt to replace natural pollinators with human labor was a costly exercise, not sustainable in a field setting.

Some interesting research has investigated the ecological interaction between the non-native honeybee and native pollinators. European varieties of the honeybee, Apis mellifera, were deliberately introduced on the Caire ranch in the 1800s, supposedly to assist with pollination of his orchards and vineyards and also to produce honey. The honeybees escaped and established feral colonies, aggressively competing with the native pollinators with which native plant species had evolved. Research by the aforementioned Dr. Robbin Thorp and Dr. Adrian Wenner of UC Santa Barbara compared the frequency of visits from native bees and introduced honeybees on the island, to try to determine if they were competing for pollen and nectar from native plants. After two years of documenting plant visitation by wild native bees and honeybees, honeybee colonies on the eastern half of the island were located and removed. Subsequent data showed that after removal of the honeybees, native bees were by far the most common visitors to manzanita flowers on the eastern half of the island; on the western side, feral honeybees still dominated such pollination visits (Beesource, 2016). Whether honeybees pollinate bush mallows or whether their competition is suppressing the native pollinators that do pollinate them is a question that research so far has not answered.

_______

This vignette of the near-demise and potential restoration of the Santa Cruz Island bush mallow is a bit bittersweet. In his essay “The Round River,” Aldo Leopold wrote:

“The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant, ‘What good is it?’ If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota, in the course of aeons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.”

It seems that some relatively heroic efforts have saved the island bush mallow, for the time being. But they have not restored its former range and ecology, part of which may depend upon the restoration of a suite of native pollinators that were affected by the introduction and partial naturalization of European honey bees. As the old English nursery rhyme warned, “All the king’s horses and all the king’s men couldn’t put Humpty together again.” We are trying, still hoping, but we don’t yet know if it is even possible to put an ecosystem together again once it has experienced such a great fall. There is lots more to the ecological story of putting Humpty together again on Santa Cruz Island. In many ways it can be held up as model of complex but generally successful ecological restoration, with a lot of lessons learned.

Let’s start with an important but relatively easy part of the restoration effort: sheep and cattle removal. Between 1981 and 1989, The Nature Conservancy removed approximately 37,000 sheep, and also the last 2,000 cattle from their part of the island. The National Park Service continued the process on the eastern end of the island between 1997 and 2000, removing about 10,000 more sheep. Native vegetation began to recover, but non-native weeds took advantage of the relaxed grazing pressure and began to expand too. European sweet fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) responded strongly, especially in overgrazed areas, and by 1991 was estimated to occur on ten percent of the island, often crowding out native vegetation.

And now, on to the pig story. Pigs had also been brought to the island in the early ranching days in the mid-1800s, and had escaped into the wild. Although not nearly as numerous as feral sheep, their ecological impact was devasting: they ate the acorns of the native oaks, and rooted for underground bulbs and roots of native plants, causing soil exposure and erosion, and also damaging invaluable archeological sites. By 2004, it was clear from the recovery plan for a number of ESA-listed species on the island that the pigs had to go. The contract to eliminate pigs went to a New Zealand company, Prohunt, Inc., a “professional vertebrate eradication contractor” (Morrison, 2007, p. 401), which fielded an eight-man team for the job. Pig-proof fences divided the island into five pig-removal zones. A tiny, doorless helicopter was used, from which a hunter in the passenger seat could shoot pigs from the air. Animal rights organizations squealed, and sued to stop the process, but the NPS and TNC prevailed with the argument that they had a legal obligation from the Endangered Species Act to save the island’s endangered species, and that there were no other effective alternatives that could quickly eliminate the non-native feral pigs. Radio-collared females reportedly called “Judas pigs” helped the hunters find and eliminate the last sneaky (male, I suppose) porcine holdouts. The pig eradication effort worked well and finished ahead of schedule; after a 15-month campaign approximately 5,000 pigs were killed, and the island was pig-free for the first time in a century and a half by 2006 (Flaccus, 2005). The fences still span the island; the pig-removal budget of approximately $5 million apparently covered their installation but not their removal.

All reports were that the Kiwis were well-liked, and once the pigs were gone, they did various other useful projects around the island until their contract ended, such as using their helicopter to haul away junk that had accumulated on top of Mount Diablo as communication equipment was being installed. I joked with Dr. Lyndal Laughrin, who was director of the research station at the time, that they should have set up a smokehouse to produce and market conservation-friendly “Save Santa Cruz Island” bacon and ham made from the culled pigs. Ecologically sustainable economic benefits are one of the three key planks of the biosphere reserve model, in UNESCO’s formulation (the others being biodiversity conservation and research and education), after all. In my international consulting work, I’ve had the opportunity to visit 35 biosphere reserves in 17 countries so far and seen many examples of local eco-enterprises. In the Golija-Studenica Biosphere Reserve in Serbia, for example, I had tasted and purchased jams and liquors made from wild berries, herbal teas from wild plants, wildflower honey, and dried wild mushrooms. So why not Santa Cruz Island pork products? Lyndal didn’t smile as he remembered those days: “We tried some of that pork,” he said, almost scowling, “but the pigs had been eating a lot of anise, and the meat tasted like…” I can’t remember—well, or won’t report—his description of the flavor, but “unpalatable” was the gist of it.

_______

And now, on to the story of the near-extinction and successful recovery of the island fox on Santa Cruz Island (I wrote about the evolution of this species in my last story). To begin, we have to step back 70 years and start with bald eagles. Bald eagles, which are highly territorial, apparently chased away any golden eagles that strayed over to the island from the mainland. Bald eagles feed along the shoreline on fish and other marine foods, often scavenging already-dead fish and marine mammals, and don’t hunt terrestrial animals. But they had become locally extinct on the Channel Islands by the 1950s because of DDT contamination. DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) was developed as the first of the modern synthetic insecticides in the 1940s and was widely used in agriculture, livestock production, and even homes and gardens at the time. The Montrose Chemical Company, whose main plant was located near Los Angeles harbor, was the largest producer of DDT in the United States from 1947 to 1982 (DDT was banned in the U.S. in 1972, but still exported). The company was allowed to discharge an estimated 1,800 metric tons of DDT from an ocean sewage outfall about two miles offshore (listed as a Superfund site by the EPA in 1996), and dump hundreds of thousands of barrels containing DDT-containing chemical waste at an ocean dumping site about 10 miles northwest of Santa Catalina Island (Sharpe and Garcelon, 2003, p. 323). Some of the barrels were reportedly punctured before dumping to make sure they sank. It is little wonder that the marine ecosystem of the entire California Bight was contaminated; DDT infiltrated marine food chains around the Channel Islands, concentrating in top predators like bald eagles and causing their eggshells to become so thin that they were crushed by incubating parents. Rachel Carson called everyone’s attention to this problem in her book Silent Spring, published in 1962, and federal regulatory actions reduced and eventually banned DDT in 1972. In the meantime, the local extinction of bald eagles left a “hole” in the defenses of the island ecosystem, and golden eagles from the mainland colonized the island around 1990. Lambs and piglets from the large wild populations of sheep and pigs on the island provided them a good food supply, and their population grew.

But when the sheep and pigs were removed as part of the ecological restoration of the island, and with the bald eagles gone and the golden eagles established, the golden eagles began hunting island foxes, which had no evolutionary fear of aerial predators. The fox population plummeted rapidly in the late 1990s, until by 2004 there were only about 100 island foxes left on Santa Cruz Island, and the fox was federally listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. That listing required a recovery plan for the foxes. The plan had two planks: one, to remove the threat factor—golden eagles; and two, to protect and expand the population of the remaining foxes. The two activities were instituted simultaneously.

Approximately three dozen golden eagles were trapped and removed by 2006. In 2002, 10 pairs of island foxes had already been brought into captivity on Santa Cruz Island to protect them from extinction (National Park Service, 2008). Given their innately mellow nature, the foxes were apparently quite cooperative when taken into captive breeding enclosures, producing tiny cute kits that were later released across the island, once the golden eagles were gone. The fox population has now rebounded to more than 2,000, probably close to natural carrying capacity of the island, according to Lyndal Laughrin. In 2016, the Santa Cruz Island fox subspecies and those on Santa Rosa and San Miguel Islands were taken off the endangered list (the Santa Catalina Island subspecies is still listed as threatened). This was “the fastest successful recovery for any ESA-listed mammal in the United States” according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

And our national bird, the bald eagle, is back, defending the island’s shores from its cousins, golden eagles. Between 2002 and 2006, 61 bald eagles were released on Santa Cruz Island, and in 2006 a nesting pair successfully hatched two chicks, the first successful nesting in over 50 years (NPS, 2008).

The art—and science—of ecological restoration on Santa Cruz Island, or anywhere else, of course, is sort of like the game of “pick-up-sticks” (or “jackstraws,” if you prefer the British name of the game). After a century and a half of both deliberate and inadvertent attack on the island’s ecosystem, if you pull out one “stick”—one introduced species—chances are it will influence the ecological “pile” of sticks, which will rearrange the pattern, and you will have another problem on your hands. Everything is connected to everything else. You can’t just do one thing. Conservation biologists and ecosystem managers on the islands are still dealing with the complexities of trying to undo and reverse the ecological damage done, and restore an ecological balance that can include and maintain the island’s unique endemic species.

For related stories see:

- The Art of Ecology: Audubon’s Oystercatchers and Other Examples, November 2014

- The Art of Ecology: A Pilgrimage to the Heart of the Andes, February 2015

- The Art of Ecology: Sketching with Cole and Church, May 2015

- In Search of the Sublime with Albert Bierstadt in Colorado, July 2015

- In Search of the Sublime with Albert Bierstadt in Brooklyn, February 2016

- Another Conversation with Thomas Cole, February 2018

- A Winter Walk with Audubon in Upper Manhattan, February 2018

- Revisiting Cole’s View of The Oxbow, April 2018

- More Ecological Explorations at the Edge of the Continent, October 2021

- Evolutionary Ecology on California’s Galapagos, January 2022

Sources and other links:

- Zoe Keller, graphite artist/ecological art

- Limuw/Santa Cruz Island, by Zoe Keller, 2017

- Byers, Bruce A. 2020. The View from Cascade Head: Lessons for the Biosphere from the Oregon Coast (Oregon State University Press).

- Nora Sherwood, biological illustration/nature art

- Golija-Studenica Biosphere Reserve, Serbia

- Santa Cruz Island Reserve, no date. “History”

- National Park Service, Channel Islands National Park. 2016. “Santa Cruz Island History and Culture.”

- The Nature Conservancy. 2021. “Santa Cruz Island.”

- Livingston, Dewey. 2011. Oral history interview with Dr. Lyndal Laughrin. University of California Santa Barbara Natural Reserve System, Santa Cruz Island Reserve.

- Santa Cruz Island Foundation

- National Park Service. 2008. Santa Cruz Island: Restoring the Balance (video)

- Growing Solutions. 2016. Santa Cruz Island Rescue and Recovery.

- McEachern, A. Kathryn et al. 2010. “Field Surveys of Rare Plants on Santa Cruz Island, California, 2003–2006: Historical Records and Current Distributions.” US Geological Survey, Scientific Investigations Report 2009–5264.