February 2015. I was in New York City recently, and on a sudden whim I decided I needed to see The Heart of the Andes. A snowstorm had passed through the previous night, dumping a few inches on the city, but the sun was out and the streets and sidewalks were slick and sloppy. I caught a crosstown cab to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Frederic Edwin Church’s giant painting is displayed in the American Wing of the museum.

In a previous blog on the relationship between art and the science of ecology, I expressed my opinion that Church’s painting, The Heart of the Andes, is an example of ecological art – art that illustrates ecological principles. I wanted to experience the painting in person and up close. It is huge – almost six feet tall and ten feet wide. But in Gallery 760 of the American Wing it is dwarfed by the gigantic, dramatic painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware on the end wall of the gallery to its left.

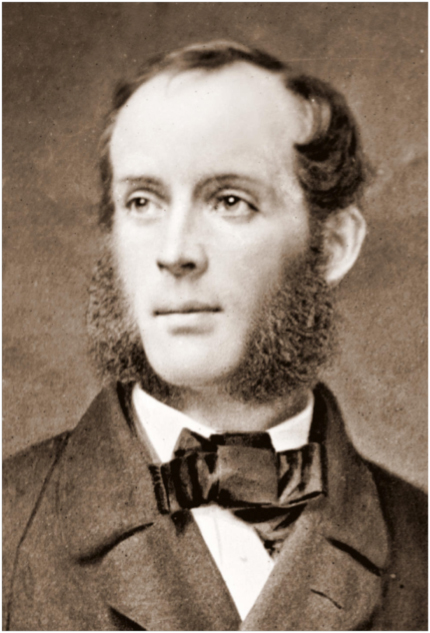

Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) was an important member of the “Hudson River School,” a group of artists who, “with Thomas Cole as their leader… created an American landscape vision based on the exploration of nature, seen as a resource for spiritual renewal and an expression of cultural and national identity,” according to the interpretive signs in the museum. The Hudson River School became the dominant artistic vision among American artists from 1825 to 1875.

Church travelled to Ecuador in 1853 and 1857, inspired by the explorations of Alexander von Humboldt (1767–1859), the great German geographer-scientist, whose ideas about complex, interdependent natural systems laid the foundation for the science of ecology. Church used dozens of pencil and oil sketches from his trips to Ecuador, and synthesized them into this painting, which reflects the full range of climates and ecosystems that Humboldt had described in his 1805 book, Essay on the Geography of Plants. The grand painting was unveiled in New York in the spring of 1859 – the same year that Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. It was displayed in a huge frame that suggested a window, and Church urged viewers to stand back and use opera glasses to examine the minute details he had painted, as if they were with him in Ecuador seeing the whole landscape.

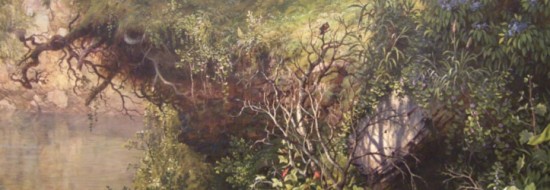

After sitting on a bench below the painting for a few minutes, taking in the landscape view – I had missed the memo to bring my opera glasses – I wandered close to the canvas to study Church’s technique. It was like walking along a trail into the scene: the closer I got, the more detail that appeared. Invisible from a distance, I was suddenly in the midst of blooming epiphytic plants, bright birds perched on branches, and butterflies fluttering over flowers. In the lower left of the painting, the date 1859 and the artist’s name is carved on the trunk of a giant tree struck by a shaft of sunlight beside blooming epiphytes. A quetzal perches on a dead limb, its cascading tail juxtaposed with a small waterfall in the background.

Church hoped to take this painting to Berlin to show to his muse, von Humboldt, but Humboldt died in May of 1859 before he could do so. The painting was exhibited in London in September, 1859, however, where it met with similar popularity as in New York. Church eventually sold it for $10,000 – at that time the highest price ever paid for a work by a living American artist.

Frederic Church was a decade-older contemporary of John Muir (1838-1914). Both idolized Alexander von Humboldt and made pilgrimages to South America following in his footsteps. Both were in the vanguard of naturalists and artists with a romantic, spiritual, systems-view of nature. So far I have found no evidence that Church and Muir ever met, although Muir did visit his friend and fellow nature-writer John Burroughs, whose home in the Hudson Valley is not that far from Church’s home at Olana. Albert Bierstadt, another Hudson River School painter, travelled to Muir’s territory, Yosemite in California, and painted a grand scene of the Yosemite Valley. But again, I have found no evidence that Muir and Bierstadt ever met.

Thomas Cole (1801-1848), founder of the Hudson River School, “…inspired many of his colleagues, including his most important student, Frederic Edwin Church, to take up plein-air sketching in pencils or oils. For Cole, the act of sketching outdoors went hand in hand with the close study of nature and was an essential tool in the creation of a significant studio painting,” stated another interpretive sign in the Metropolitan Museum. For me, the phrase “the close study of nature” suggests the common ways in which nature artists and ecologists do their work.

Cole’s oil “sketch” for his later studio painting, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm – The Oxbow (1836), Metropolitan Museum of Art

Some of the interpretive placards in the American Wing give unexplained but tantalizing tidbits about the relationship between art of the Hudson River School and ecology. For example, in one titled “Late Hudson River School, 1860-80”, we read: “In addition, new scientific theories involving natural law – foremost among them, Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) – contributed to the changes in landscape art. In their preoccupation with light, these painters articulated simultaneously their interest in naturalistic effects and their perception of the spiritual essence of nature.” Maybe that latter phrase is a gentle way of alluding to the fact that these nature romantics of that era – artists like Cole, Church and Bierstadt, writers like David Henry Thoreau and John Muir, and scientists like Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace – were beginning to see the natural world as a spiritual reality far more tangible than was an abstract Judeo-Christian “god.”

A small painting, Hummingbirds and Passionflowers, by Martin Johnson Heade, is displayed just to the right of The Heart of the Andes – fitting, because Church also depicted passionflowers in the detail in the lower right corner of his painting. Heade (1819-1904) was a naturalist and painter with a passion for hummingbirds, who travelled to the Amazon Basin more than once to study and paint them. He was familiar with the work of Charles Darwin, who in The Effects of Cross and Self Fertilisation in the Vegetable Kingdom (1876), specifically mentioned the adaptation of hummingbird beaks to fertilize passionflowers. This painting illustrates an example of co-evolution and symbiosis used by Darwin, and is thus a clear, early example of explicitly ecological art.

In his essay Church, Humboldt, and Darwin: The Tension and Harmony of Art and Science, Stephen Jay Gould wrote: “Church did not doubt that his concern with scientific accuracy went hand in hand with his drive to depict beauty. His faith in this fruitful union stemmed from the views of his mentor Alexander von Humboldt.” In the second volume of Cosmos, his magnum opus, Humboldt included a chapter on the influence of landscape painting on the study of the natural world, and expressed his opinion that it ranked as one of the highest expressions of the love of nature. He challenged artists to portray the unity of the interconnected systems that underlie any landscape – in essence to portray the ecosystem as well as its component parts.

Mark Twain (1835-1910), described Church’s painting The Heart of the Andes to a friend: “You will never get tired of looking at the picture, but your reflections—your efforts to grasp an intelligible Something—you hardly know what—will grow so painful that you will have to go away from the thing, in order to obtain relief. You may find relief, but you cannot banish the picture—it remains with you still. It is in my mind now—and the smallest feature could not be removed without my detecting it.”

Twain’s statement called to my mind the last paragraph of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, and I moved closer to the painting again to see the detail Church had painted in the lower right: “It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

These scientists, artists, and nature philosophers of the 19th Century were the vanguard of a systems view of nature, the view that is now the foundation for the science of ecology. We need that so much now! We have not yet implemented their worldview, but that is what could, maybe, save us from the ecological stupidity and self-destructiveness of our own species.

For related stories see:

- The Art of Ecology: Audubon’s Oystercatchers and Other Examples

- At Church with John Muir

- Visiting Revolutionary Ecological Relatives in Philadelphia

Related links:

- The Heart of the Andes in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Washington Crossing the Delaware in Gallery 760

- Albert Bierstadt and Yosemite

- The Roots of Preservation: Emerson, Thoreau, and the Hudson River School

- Frederic Church and the Hudson River School as Conservation Catalysts

- Martin Johnson Heade: Passion Flowers and Hummingbirds

- Church, Humboldt, and Darwin: The Tension and Harmony of Art and Science. Stephen Jay Gould. 2000.

March 12, 2015 2:39 am

Bruce, this is a remarkable, beautiful, erudite and enlightening interpretation and elucidation of “Art of Ecology….” I feel like I now need to make a pilgrimage to NYC’s Metropolitan Museum of Art to view Frederick Church’s The Heart of the Andes. I really like also how you tie together von Humboldt, Twain, Stephen Jay Gould, Darwin, et alia. I can certainly relate to the idea of the natural world as a spiritual reality.

Thank you!

Walter

March 13, 2015 7:39 pm

I’m glad you enjoyed this piece, and thanks for the generous words. I’m sure you would enjoy seeing The Heart of the Andes. When you do, let me know what you think.