November 2014. After visiting John James Audubon’s (1785-1851) first home in America, Mill Grove, not far from Philadelphia, I was looking again through his masterwork, Birds of America. When I came to the plate of the Black Oystercatcher, I realized that his artist-naturalist’s eye had noticed that it is a predator of limpets – those flat, volcano-shaped cousins of spiral-shelled snails. In his portrait of the species, Haematopus bachmani, he illustrated that ecological relationship – one of the birds was stabbing at a pair of limpets at the base of the rock on which the second bird stood. I spent a couple of summers in the tidepools of Cape Arago, Oregon, investigating the ecological results of the Black Oystercatcher’s predilection for limpets. In the “aha!” moment when I realized that Audubon’s ecological art predated my scientific study by more than a century, I got a new perspective on something I’ve been puzzling about for a long time: the relationship between art and ecology.

It has always felt perfectly natural to me to mix scientific and artistic ways of perceiving the world, but when I was in graduate school there was much talk of the “two cultures” of science and the arts and humanities. Many people then thought of them as very different ways of experiencing and knowing the world – and many still do, it seems. They imagine that there is a gulf between science and the arts; some people even think of them somehow as “opposites.” I have long been puzzled about this cultural schizophrenia, which I have never felt.

So, after seeing Audubon’s oystercatcher painting, I googled “art and ecology.” Try it yourself if you are interested in what people are discussing under that heading out there in the cyber “cloud.” The first “hit” was “Art&Ecology,” an “interdisciplinary, research-based academic program engaging contemporary art practices” at the University of New Mexico. The second hit was the Occidental Arts and Ecology Center, “a non-profit education center in Sonoma County, California, that works to promote ecologically and culturally resilient communities.” The third hit was the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, a non-profit institute located on the Oregon Coast, not far north of my old Cape Arago research site, whose mission is “expanding the relationships between art, nature and humanity.” Etcetera. There were many more hits as Google reached into the fog of the cyber cloud that envelops us all now, searching for contemporary wisdom on “art and ecology.”

Probing deeper in these various websites, however, turned up almost nothing about the relationship between “art and ecology,” the search terms I had typed in. The websites were for arts institutes specializing in nature art, or organizations trying to foster art in the service of environmentalism. Both are worthy subjects, of course. Nature is a beautiful, rich subject for arts of all kinds. Audubon himself recognized the need for bird conservation, and the Audubon Society was founded in his name by George Bird Grinnell and other early conservation leaders. But I didn’t really find much on the web that explored the philosophical and cultural relationship between the science of ecology and the arts – in other words, the art of ecology, or ecological art.

Maybe we should start from scratch, then. One first step in understanding the relationship between ecology and art would be to list some fundamental ecological ideas or principles, and ask whether any art reflects those. This approach might be called the “ecology and art” hypothesis: if there is a relationship between ecology and art, then some art will reflect ecological principles. Here are a handful of some of the most fundamental ecological ideas:

- Energy flows from the sun through plants to animals

- Materials like water and carbon cycle in ecosystems

- Species are linked in food chains and food webs

- Humans are part of ecosystems, like all species

- Ecosystems have emergent properties because of their complex interdependencies; everything is connected to everything else, and the whole is greater than the sum of the parts

Is there any art that reflects any of these principles? Any “hits” here?

Of course! Audubon’s portrait of the Black Oystercatcher! His painting of that species depicted an ecological understanding of its food chain, and of its visual hunting behavior. It is a study in behavioral ecology – a clear example of ecological art, already in the early 1800s. In fact, Audubon illustrated simple food chains in many of his avian portraits, showing not only the species but its prey, including in some of his paintings of herons, cranes, nightjars, owls, bluebirds, robins – and even his surreal Golden Eagle, suspended over snowy peaks and rocky chasms in a stiff, stuffed, non-flight position, clutching a pure white snowshoe hare in its black talons.

Have we come any further now in our understanding of the relationship of ecology and art? If you search for the terms “art and ecology” in the cyber-cloud you won’t find much evidence that we have.

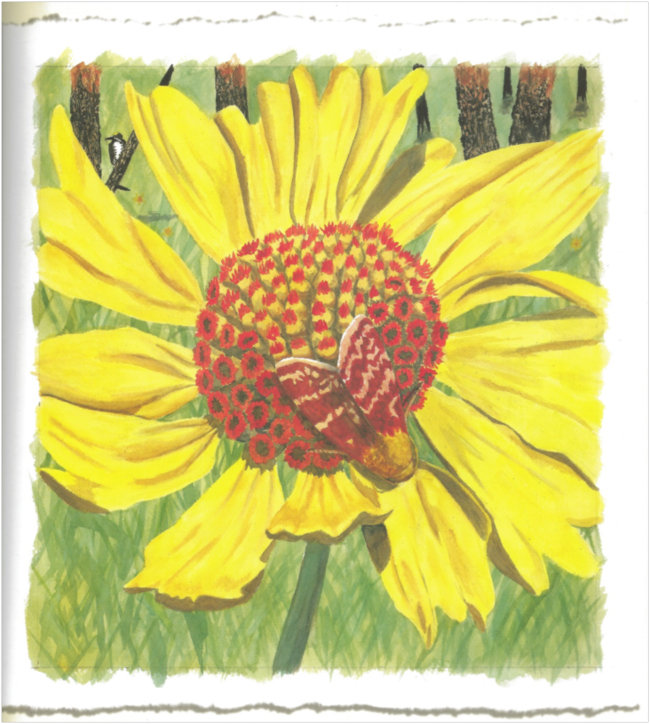

However, I happen to know of a recent book that is a wonderful example of visual art that illustrates ecology: The Charcoal Forest: How Fire Helps Animals and Plants, by Beth Peluso. The book is essentially a primer of fire ecology for kids. Peluso illustrates twenty species that that are somehow fire-adapted or fire-dependent, species that benefit from the ecological disturbance of fire. Fire sets in motion a process of ecological succession that eventually supports many more species that a non-burned forest could. Although aimed at children, the art here shows a sophisticated understanding of ecological relationships. I know of this book because it features an illustration of the Colorado Firemoth, Schinia masoni, based on my research on that species. This beautiful moth is camouflaged, in gaudy red and yellow, on blanketflower, a fire-dependent wildflower of the Colorado Front Range.

And, digging back deeper in time, I see examples of ecological art in indigenous art. An Inuit print from Cape Dorset, in the Canadian Arctic, for example, is a perfect illustration of the ecological principle that humans are part of ecosystems, woven into food webs like all species.

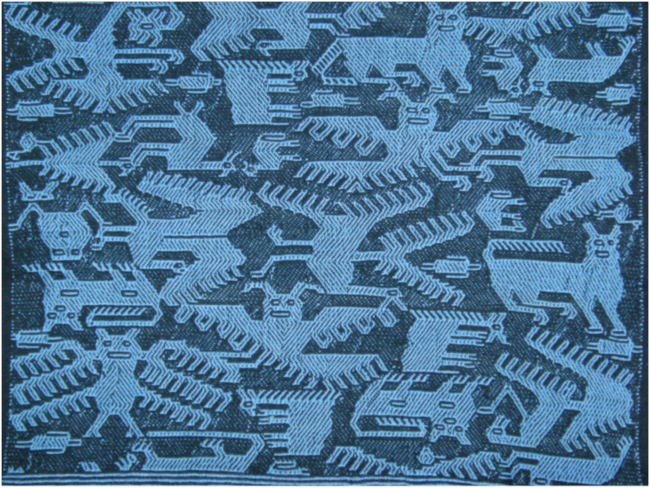

In traditional Jalq’a weaving from the Bolivian Andes we see the same indigenous ecological insight. See how tiny people are there, fitting into an Escherian ecosystem among the condors and pumas, the vicuñas, guanacos, rabbits, eagles, bats and toads? This art shows people as part of nature – a tiny part.

And this is the same message as in Frederick Edwin Church’s giant oil-on-canvas landscape painting, “The Heart of the Andes” (1859). Church’s travels and painting in the Andes were inspired by Alexander von Humboldt (1767-1859), the great German geographer-scientist, whose ideas about complex, interdependent natural systems laid the foundation for the science of ecology.

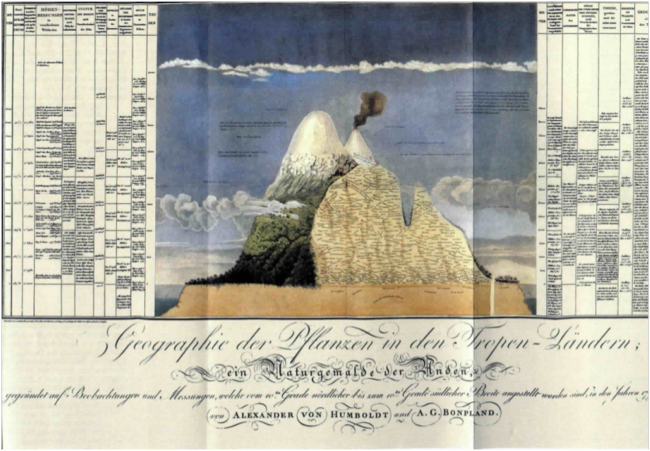

Church’s painting showed the volcano Chimborazo, far in the distance, which Humboldt and his travelling companions had almost managed to climb in 1801, reaching an altitude of almost 20,000 feet, only about 1,000 feet below the summit. Humboldt illustrated the distribution of vegetation on Chimborazo in altitudinal zones in a figure in his 1805 book Essay on the Geography of Plants that is recognized as one of the most creative pieces of scientific art and communication ever.

In his essay Church, Humboldt, and Darwin: The Tension and Harmony of Art and Science, Stephen Jay Gould wrote: “Church did not doubt that his concern with scientific accuracy went hand in hand with his drive to depict beauty…. His faith in this fruitful union stemmed from the views of his mentor Alexander von Humboldt.” In the second volume of Cosmos, Humboldt included a chapter on the influence of landscape painting on the study of the natural world, and expressed his opinion that it ranked as one of the highest expressions of the love of nature. He challenged artists to portray the unity of the interconnected systems that underlie any landscape – in essence to portray the ecosystem as well as its component parts. Art historian Chunglin Kwa of the University of Amsterdam, in a 2005 article titled Alexander von Humboldt’s Invention of the Natural Landscape, wrote that “Humboldt looked at plant vegetation with a painterly gaze. Artists, according to him, could suggest in their work that an abstract unity lay hidden underneath observable phenomena.” Frederick Church did that.

Laura Dassow Walls, in her thought-provoking analysis of Humboldt’s influence on modern thought, The Passage to Cosmos: Alexander von Humboldt and the Shaping of America, writes that “Recovering his [Alexander von Humboldt’s] cosmopolitan and multidisciplinary prospect means… revisioning science as an intrinsic constituent of the humanities, reading beyond the “two cultures” to grasp a worldview that knew how to distinguish the natural and social sciences, the arts, and the humanities, but knew also how fully each interpenetrated all the others.”

As I see it, scientists and artists are very similar in their modes of perception and methods of working. If you look at the Myers-Briggs personality profiles of artists and scientists, and compare them to the full spectrum of other human occupations, you will see that scientists and artists mostly fall within one-quarter of the “personality space” of human personalities. The commonalities are that artists and scientists observe carefully, but seek underlying patterns below the surface of sensory information, which they abstract and communicate symbolically, whether in scientific hypotheses, paintings, or poems. For an artist, or an ecologist, the deeper pattern is where the meaning lies.

Observation and attention to pattern… hmmm. Even oystercatchers do that, hunting for limpets on intertidal rocks. Observation and attention to pattern are fundamental to the survival of all animals. They are common to all humans, not only scientists and artists. Because evolution has tuned all of us to observe and pay attention to patterns in our environment, science and art are part of our deep evolutionary heritage, inextricably intertwined in our genes. The supposed gap between scientific and artistic ways of perceiving the world is a fundamental misunderstanding.

Yet, for example, on the website of the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, in an article about what it is like for scientists and artists to be in residency together at the center, a scientist is quoted as saying that “For any ecologist it is helpful to be around people who are the antithesis of what you do.” Such a statement implies that for him, art and the science of ecology are opposites, dichotomous poles of human experience. I can’t understand how an ecologist could feel or say that. As long as some scientists can and do say such things, however, it is important to bring them together with artists to experience a common environment and dispel the myth that artistic and scientific modes of perception are antithetical. I suspect they would rediscover what scientists and artists like John James Audubon, Alexander von Humboldt, and Frederick Church knew more than 150 years ago.

For related stories see:

- Visiting Revolutionary Ecological Relatives in Philadelphia. July 2012.

- Colorado Fires and Firemoths. June 2013

Related links:

- The Black Oystercatcher. Plate 427, Birds of America. John James Audubon.

- Habitat-Choice Polymorphism Associated with Cryptic Shell-Color Polymorphism in the Limpet Lottia digitalis. Bruce A. Byers. 1989. Veliger 32:394-402.

- The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. C.P. Snow, the Rede Lecture, 1959. Cambridge University Press. 1961.

- Art&Ecology

- Occidental Arts and Ecology Center

- Sitka Center for Art and Ecology

- The Charcoal Forest: How Fire Helps Animals and Plants. Beth A. Peluso. 2007. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, MT.

- Symposium – Alexander von Humboldt and the Order of Nature: Aspects of Culture and Landscape in the Americas. Americas Society/Council of the Americas. Hunter College, New York, NY. April 30, 2014 (webcast).

- Church, Humboldt, and Darwin: The Tension and Harmony of Art and Science. Stephen Jay Gould. 2000. Pp. 27-42 in Latin American Popular Culture: An Introduction. SR Books, Rowman & Littlefield. Lanham, MD.

- The Passage to Cosmos: Alexander von Humboldt and the Shaping of America. Laura Dassow Walls. 2009. University of Chicago Press.

- Gifts Differing: Understanding Personality Types. 1980 and 1995. Isabelle Briggs Myers with Peter B. Myers. CCP, Inc.

June 13, 2017 1:00 am

This is awesome Bruce, thank you so much for bringing this into a discussion.

I just ended here by googling Church’s artwork after reading “The invention of nature” by Andrea Wolf.