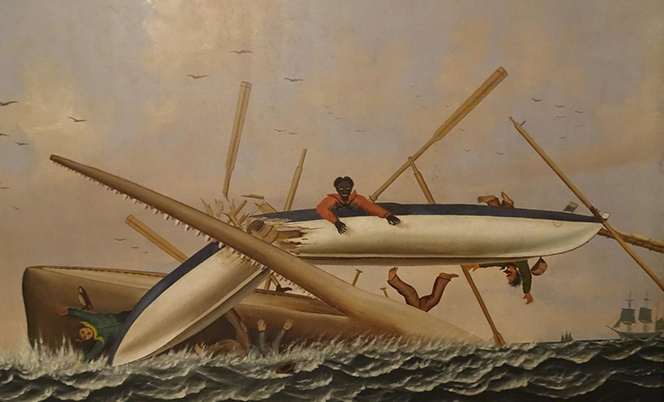

On a recent trip to Cape Cod, we spent the first night in New Bedford, Massachusetts, once known as “the city that lit the world” because its whaling fleet was the largest in the world and whale oil was the fuel of choice for oil lamps (and spermaceti, from sperm whales, for the best candles). The New Bedford Whaling Museum proved to be a wonderful portal into the history of American whaling, and we spent most of the next day there.

“Burning the midnight oil” became a phrase signifying industriousness—surely a New England, if not an all-American, virtue. Before home lighting was so widely available, the image, I guess, is that people ate dinner, went to bed early, and therefore had lots of babies. At its zenith, in 1857, the year of Henry David Thoreau’s fourth and last trip to Cape Cod, New Bedford was the “whaling capital of the world,” the home port of 329 whaling vessels. Its whaling industry employed over 10,000 men, half the city’s population. The whale-oil business wasn’t just whaling ships and their crews; it included a range of supporting industries: shipbuilding, cooperage, and chandlery; whale-oil refineries and spermaceti candle factories; sales and transport of whale-oil products to both domestic and international markets; and—because whaling was both a lucrative and risky business—banking and insurance services.1 By 1900, whaling had crashed because of overhunting, and only 29 whaleships were still docking in town; textile production had taken over as the main local industry.

New Bedford had earlier eclipsed Nantucket, the first whaling capital of the world, which had held that title from the beginning of American whaling in the 1700s until around 1815, when it hosted 47 whaling ships. By 1828, New Bedford’s whale fleet had overtaken Nantucket’s, with over 80 ships.

Part of my curiosity about global whaling arose after learning, during my research for my new book about California’s coastal biosphere reserves, that San Francisco had stolen the last gasps of whaling from New Bedford after the Civil War, and took over the title of the world’s biggest whaling port in the 1880s.

_______

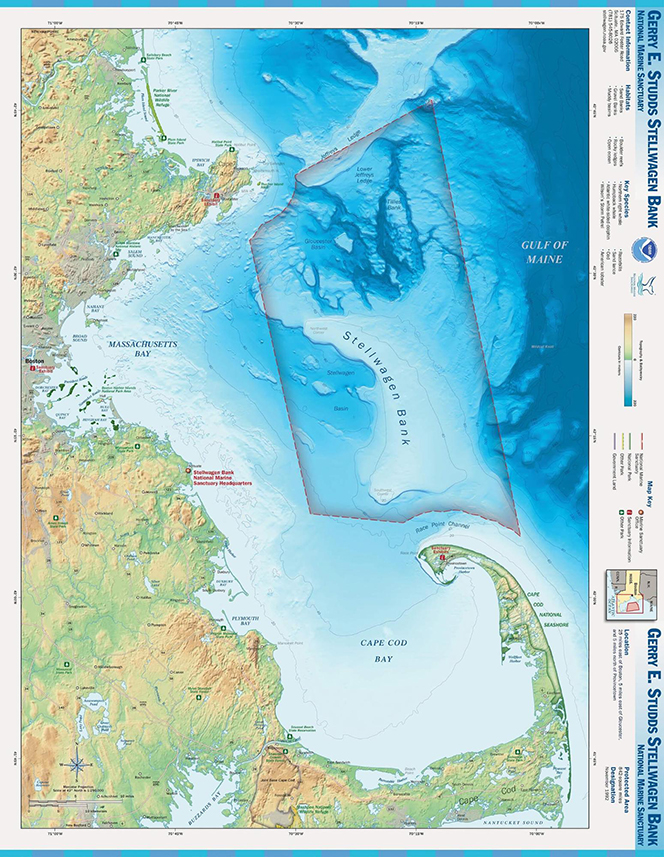

We departed Provincetown harbor at 10 AM on a calm, sunny morning, on a Dolphin Fleet2 whale-watching trip, bound north for Stellwagen Bank, a NOAA National Marine Sanctuary.3 There, undersea topography combines with currents to create upwelling, bringing nutrients to the surface, which causes blooms of planktonic marine plants, supercharging marine food webs, and providing rich feeding grounds for baleen whales. Baleen whales are the ones that strain small food—small fish like anchovies, or shrimp-like crustaceans like krill—from the water with a sieve-like structure built into their upper jaw. Although distantly related, they have almost the opposite strategy, and anatomy, as the toothed whales, who’s sharp, wolf-like teeth are used to capture big prey: picture Moby Dick, a sperm whale, whose kind hunt giant squid in the deep ocean. Or orcas, “killer whales,” who hunt a variety of large marine mammals, including baleen whales, in social groups, the wolves of the sea.

The southeast corner of Stellwagen Bank is only about five miles north of Race Point, the northernmost tip of Cape Cod, although it took at least half an hour to make the run there, because the route circled out around the “hook” of the Cape, which arcs around Provincetown harbor. We saw a few whale spouts as we travelled toward Stellwagen Bank, but the boat captain was obviously making a run for where the morning humpback-whale feeding action was likely to be happening.

And it was. We soon encountered a female humpback with her this-year’s calf, and they provided at least an hour of delight-making observations. I say “delight-making,” because it delighted me. But, really, how can I describe the emotion, and what can I call it? To see this glimpse into another, non-human world was why I had come, and why all of the other passengers on this boat had come. The behaviors we observed gave a glimpse into the personal relationships of a mother and child who weren’t human… but who obviously, as we could see, had a close, tender, emotional relationship.

When mom dove to feed, the calf loitered on the surface, splashing and spinning, cavorting and playing. In a few minutes a curtain of bubbles would emerge from below, a bubble net that surrounded and drove the tiny fish the mother humpback was gulping down. The calf was learning how to find food, and mom was hungry from nursing.

The scientific name of the humpback whale,4 Megaptera novaeangliae, means “big-winged New Englander,” reflecting the region where European whalers first encountered—and started killing—this species. Humpbacks are distinguished by their large, wing-like pectoral fins, hence the “megaptera.” They have been photographed at Stellwagen Bank for a long time, and a library of photos has allowed whale researchers to construct a database of individual whales that can be identified by their unique fin and fluke anatomy and coloration patterns. It wasn’t too long before the naturalist on board our trip was able to identify this female as “Dross.” Her calf, without a name yet, was born last winter in the calving grounds of these New England humpbacks, probably in the vicinity of the northeastern Dominican Republic, with known breeding and calving grounds at Silver and Navidad Banks and Samana Bay. NOAA has identified 14 stocks, or “distinct population segments,” of humpback whales worldwide, and the Stellwagen and other New England humpbacks belong to a population that breeds in the West Indies. The non-profit Provincetown-based Center for Coastal Studies has facilitated and coordinated the science and citizen-science that is constructing this picture of the whales seen off Provincetown and their annual journeys between breeding and feeding grounds.5

_______

Male humpback whales have been called “the jazz singers of the sea” because of their amazing vocalizations. Humpback “songs” are unique among whales because of their musical structure, with repeated phrases and themes, and variations that suggest improvisation, like in jazz music. Moving across a wide sound spectrum from extremely low to very high frequencies, one humpback song can last for 30 minutes and be repeated for a whole day. The phenomenon of humpback whale songs was first recognized by biologist Roger Payne,6 who saw what he called these “exuberant, uninterrupted rivers of sound” as having the potential to motivate whale conservation if more people heard them. They have been called “the songs that saved the whales.” In the late 1960s Payne began distributing recordings of humpback songs to musicians and composers. One of those was Judy Collins, who took an old traditional whaling ballad, “Farewell to Tarwathie,” and created a duet with a humpback from one of his recordings.7 Her song resonated strongly with me and many others at the time, and I played it in my university ecology and conservation classes for many years, trying, I guess, to sneak in a message about the compatibility of science and emotion. What better spokesperson for that perspective could there be than a jazz-singing humpback?

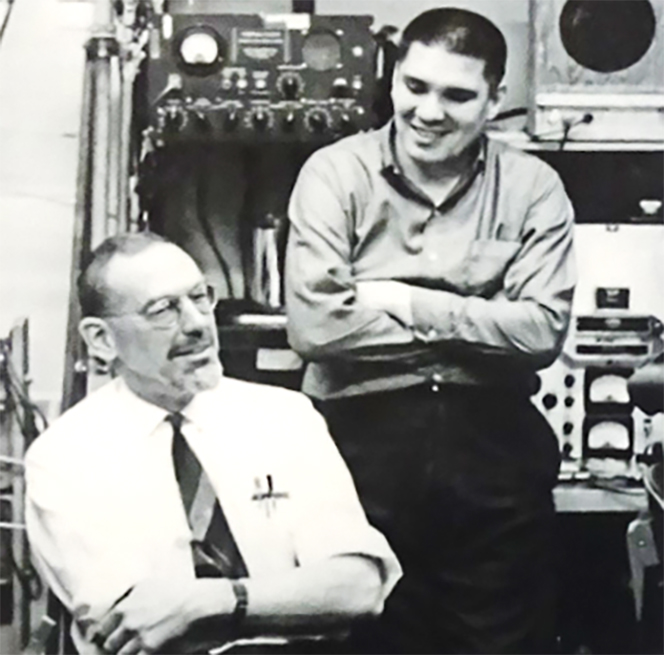

But at the New Bedford Whaling Museum I learned about the even deeper and more improbable background of how “the songs that saved the whales” came to be first heard, and recognized. William Schevill. a curator at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, was recruited during World War II by the US Navy’s anti-submarine warfare team to identify underwater sounds believed to be made by submarines. He determined that what they were worried about were actually the calls of fin whales. William Watkins joined Schevill in recording and cataloguing distinctive whale sounds, collaborating with him for almost 40 years. Their work is the foundation of marine bioacoustics. It was Schevill and Watkins’s recording that first caught the attention of Roger Payne.8 The New Bedford Whaling Museum now holds the Schevill-Watkins collection of over 18,000 recordings of the sounds of whales and other marine mammals; it is accessible to the public online.9 The museum has also highlighted what they call the 64 “Best of Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)” sounds. Most are very short, a few seconds of blips, bleeps, and trumpet blasts, but a couple are ten minutes long or more—fun listening!10

_______

A film produced by the Nantucket Historical Society, “Nantucket,” by Ric Burns,11 makes much of the fact that many, perhaps a majority, of the whaling captains, ship owners, and whale-oil barons were Quakers. The script attributed this in part to the seriousness and industriousness of Quakers, but also to the fact that women in Quaker society were treated very much as equals, in contrast to many other patriarchal Christian sects. If her husband had to be away at sea for four years, chasing whales in the Pacific, the dutiful Quaker wife could burn the midnight oil, keep the books, manage the household, and faithfully await his return. An interesting hypothesis, and I wanted to examine it further. The whaler-Quaker correlation seems to stem partly at least from the geographical overlap of whaling and American Quakerism, at least Quaker history in New England.

George Fox founded the Religious Society of Friends, the Quakers, in England in 1646, and eager Quaker missionaries began to arrive in Massachusetts soon after. But the Puritan religious authorities then reigning in Boston had “no tolerance for this cursed sect of heretics and their absurd and blasphemous doctrines.” A law was passed in 1657 that fined or imprisoned anyone caught entertaining or concealing a Quaker. Among Quaker beliefs was the idea that “God resides in every human being and that direct communication with God can be made without assistance from clergy or intermediaries.”12

Damn! That was radical! It totally upset the patriarchal, hierarchical structure of Christianity dating back to… well, almost its beginnings. Based on that heretical belief, Quakers supported equal status and rights for women, and all races. They refused to swear allegiance to political authorities. The latter practice made them pacifists, and they refused to bear arms in political conflicts, making them one among the three historic American peace churches, along with the Brethren and Mennonites.

An early American convert to Quakerism, Nicholas Upsall, was jailed in Boston and then expelled from the city in 1656. He fled to Sandwich, where he apparently found a warm welcome among people dissatisfied with puritanical strictures. The first open, official meeting of the Society of Friends in America, was in 1657, in Sandwich. A century and a half later, in the late 1700s, when the whaling industry was taking off, “most merchant families from Nantucket and the coastal mainland were Quaker by birth and in practice.”13

The human egalitarianism of the Quakers proved good for the business of whaling. Quaker women were enculturated to be empowered and strong, so if their men were away at sea, they could manage family and business affairs. If a fugitive or free slave, or American Indian or Hawaiian Islander, wanted a low-wage, dangerous job on a whale ship or in a whale-oil factory, they were welcomed. The Azores and Cabo Verde, Atlantic archipelagos administered Portugal, were frequent resupply points for whaling ships, and many men from both places were recruited onboard, eventually emigrating to New Bedford and providing a key labor force for the whaling industry. They added a non-slave African and Portuguese dimension to the diversity of city, mixing easily into the city’s tradition of tolerance. Quaker industriousness and tolerance began to contribute to their success in whaling, and eventually made many Quakers captains of the industry and wealthy whale-oil magnates.

But the Quakers, like all adherents of Middle Eastern monotheisms (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), were myopically anthropocentric. Their belief that God resides in every human being did not extend to nonhuman species—the myriad other beings we share the planet with. Their ecological blindness apparently allowed them to feel virtuous exterminating whales while arguing for an end to slavery.

_______

And now, let’s bring Henry David Thoreau into the Quaker-whaler tableau. Walden was published in 1854, and was soon receiving many reviews, mostly positive. “Walden soon brought Thoreau fan letters and new friendships.”14 The book’s success tempted Thoreau to contemplate going on the lecture circuit, following the footsteps of his mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson, who by then was travelling the country giving paid lectures. Henry soon started to get paying lecture engagements: Plymouth, Philadelphia, and in Providence, Rhode Island, where he delivered a brand-new lecture, “What Shall It Profit?” The Providence audience was cool to the new material, which urged them to make a living by doing the things they loved, not merely those society valued. Its titled was taken from the New Testament, Mark 8:36: “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” Despite the reception in Providence, Thoreau honored his commitments to deliver “What Shall It Profit?” to the New Bedford Lyceum on the day after Christmas, 1854, and to the Nantucket Atheneum two days later.15 Now, perhaps, you get a sense for where this link between Thoreau, whalers, and Quakers is going.

Daniel Ricketson was a wealthy New Bedford Quaker who “had given up a career in law to live on the fortune his great-grandfather had made in the whaling industry.” He had read Walden and had written fan letters to Thoreau. When Ricketson heard that Thoreau was lecturing in New Bedford, he invited him to stay with his family. Thoreau travelled to New Bedford from Concord on Christmas Day, 1854, and stayed with the Ricketsons before his lecture the next day; thus began “a remarkable friendship” between the two men.16 The New Bedford audience reacted warmly to the lecture, but Thoreau biographer Laura Dassow Walls noted that Henry should not have gauged the impact of his message by the audience:

New Bedford was a seaport boomtown riding high on the whale-oil industry; and the lecture hall was filled with wealthy merchants, captains, carpenters, coopers, and sailors on shore leave, all dedicating their lives to reaping the ocean for huge profits. What sense could they have made of Thoreau's warning that the pursuit of profit would cost them their souls?17

The next day he sailed over rough seas to Nantucket, thirty miles offshore, seasick all the way, and spent the night recovering in the home of a retired whaling captain. Always the disciplined journalist, even after such a day, Thoreau noted in his journal for December 27:

A head wind and rather rough passage of three hours to Nantucket, the water being thirty miles over. Captain Edward W. Gardiner (where I spent the evening) … said you must have been a-whaling there before you could be married, and must have struck a whale before you could dance. It was Edmund Gardiner of New Bedford (a relative of Edward's) who was carried down by a whale.18

Like Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick. Perhaps Edmund Gardiner was a model for Herman Melville’s character in the novel, an archetype of human hubris when confronting nature.

Thoreau gave his lecture on December 28; “Three times before his lecture had bombed, but the worldly Nantucketers loved it.”19 On the 29th he was on his way home. As for the crossing back to the mainland from Nantucket, in contrast to the rough passage over, he wrote in his journal: “Still in mist. The fog was so thick that we were lost on the water; stopped and sounded many times.” Home at last, Thoreau’s journal entry on the last day of 1854 seems to find him at peace in nature after the stress of travel and lecturing: “A beautiful, clear, not very cold day. The shadows on the snow are indigo-blue. The pines look very dark. The white oak leaves are a cinnamon-color, the black and red oak leaves a reddish brown or leather-color. … How glorious the perfect stillness and peace of the winter landscape!”

“What Shall It Profit?” was conceived by Thoreau as a twin lecture to “Walking.” It evolved a new title, “Life Without Principle,” and was worked into a manuscript as he was dying; it was published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1863, only a few months after his death. You can read “Life Without Principle” on The Atlantic’s web archive.20

In his lecture “What Profit It A Man,” and the later published version, “Life Without Principle,” Thoreau has harsh words about the California gold rush, which began in 1849 and was in full swing as he lectured:

The rush to California, for instance, and the attitude, not merely of merchants, but of philosophers and prophets, so called, in relation to it, reflect the greatest disgrace on mankind. That so many are ready to live by luck, and so get the means of commanding the labor of others less lucky, without contributing any value to society! And that is called enterprise!21 I did not know that mankind were suffering for want of gold. I have seen a little of it. I know that it is very malleable, but not so malleable as wit. A grain of gold will gild a great surface, but not so much as a grain of wisdom.22

But his lecture makes no mention of whales, or the whaling industry. This seems to be a moral blind spot for Thoreau, something he couldn’t see. He was, after all, probably writing his journals, books, and lectures partly by whale-oil lamplight or spermaceti candlelight. What of the plight of the great whales, being hunted to the brink of extinction, and some species over the brink, even as he lectured to the whale-men and whale-women of New Bedford and Nantucket?

There also seems to be no mention of this issue in Thoreau’s journal at this time. Did he think of it? Or could he simply not see it, because of his historical context? One of my favorite insights from Thoreau relates to “seeing.” He wrote in his journal on August 5, 1851, “the question is not what you look at, but what you see.” He obviously looked at the New England whaling industry, but somehow didn’t see its global consequences for the whales. If he had “seen” the moral problem with whaling, I’m sure he would have spoken out about it, as he did with slavery and many other issues. He was never shy to challenge what he saw as wrong in the world.

We will never know for sure, but, even if his inability to see the ecological injustice of whaling could be interpreted as some kind of a moral failure, I can’t go there. It has become fashionable in our politically polarized, culture-warring times, to criticize some of the heroes of American nature conservation. John Muir, and more recently, John James Audubon, for example. Are we going to add Henry David Thoreau to the list because he didn’t speak out for whales in New Bedford and Nantucket?

Besides “what shall it profit a man,” there are a couple of other pieces of advice in the good book that over-woke, revisionist critics of our eco-philosophical ancestors should heed. One is, “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast the first stone,”23 Another, “Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother’s eye.”24

Even if Thoreau, and even his Quaker friends, did not see their ecological-ethical obligation not to exploit whales, is that much different from our own eco-ethical failure to stop burning fossil fuels that we know are changing the climate of our planet? Let him who is without sin first cast the beam out of his own eye!

For related stories see:

Notes and sources:

1 New Bedford Whaling Museum interpretive displays.

2 Dolphin Fleet of Provincetown Whale Watch, https://whalewatch.com/

3 NOAA Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, https://stellwagen.noaa.gov/

4 NOAA Fisheries, “Humpback Whale,” https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/humpback-whale

5 Center for Coastal Studies, “Gulf of Maine Population Research,” https://coastalstudies.org/humpback-whale-research/gulf-of-maine/; “Gulf of Maine Humpback Whale Catalogue,” https://coastalstudies.org/humpback-whale-research/gulf-of-maine/gom-humpback-catalog/; “Breeding Ground Research,” https://coastalstudies.org/humpback-whale-research/breeding-grounds/.

6 Sam Roberts, “Roger Payne, Biologist Who Heard Whales Singing, Dies at 88,” New York Times, June 14, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/14/science/roger-payne-dead.html

7 Judy Collins, “Farewell to Tarwathie,” Whales and Nightingales (1970), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjfkQtSNKl4

8 Roberts, “Roger Payne, Biologist Who Heard Whales Singing,” https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/14/science/roger-payne-dead.html

9 New Bedford Whaling Museum, “The William A. Watkins Collection of Marine Mammal Sound Recordings and Data,” https://www.whalingmuseum.org/collections/highlights/watkins-marine-mammal-sound-recording/

10 New Bedford Whaling Museum, “Best of Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae),” https://cis.whoi.edu/science/B/whalesounds/bestOf.cfm?code=AC2A

11 “Nantucket,” a film by Ric Burns, Nantucket Historical Society, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YBECX2hE7rY

12 Sandwich Friends Meeting House, interpretive display on Quaker history.

13 Nantucket Whaling Museum, “The Quaker Influence,” interpretive display, June, 2023.

14 Laura Dassow Walls, Thoreau: A Life (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017), page 362.

15 Walls, Thoreau: A Life, pp. 368-369.

16 Walls, Thoreau: A Life, p, 369.

17 Walls, Thoreau: A Life, p. 370.

18 Thoreau Journal VII, Ch. 4, December 1954, https://www.walden.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Journal-7-Chapter-4.pdf

19 Walls, Thoreau: A Life, p. 371.

20 Henry David Thoreau, “Life Without Principle,” The Atlantic, https://cdn.theatlantic.com/media/archives/1863/10/12-72/131953993.pdf

21 Thoreau, “Life Without Principle,” p. 487.

22 Thoreau, “Life Without Principle,” p. 488.

23 Bible, King James Version, John 8:7.

24 Bible, King James Version, Matthew 7:5.

August 7, 2023 8:28 pm

Hi Bruce….”delightful”…i always love new information about cetaceans.

The Quaker connection was interesting, sort of like Quakers and Chocolate! Many of us in the whale world in the 70s thought that Katie Payne deserved more recognition for her work on whale songs along with Roger.

Sounds like a great trip! Meanwhile much controversy here over Oppenheimer. BB

August 8, 2023 5:18 am

Glad if you found new information about whales here. Sounds like you have new information for me… Quakers and chocolate? I don’t know anything about that connection. And the Katie Payne contribution to the whale songs story? Please tell us!