August 2014. The wind across Tuolumne Meadows was stronger and cooler than we had expected for mid-August as we parked at the trailhead and started on the John Muir Trail for Cathedral Peak.

In My First Summer in the Sierra, describing the summer of 1869 but only published in 1911, Muir wrote, as if from his journal:

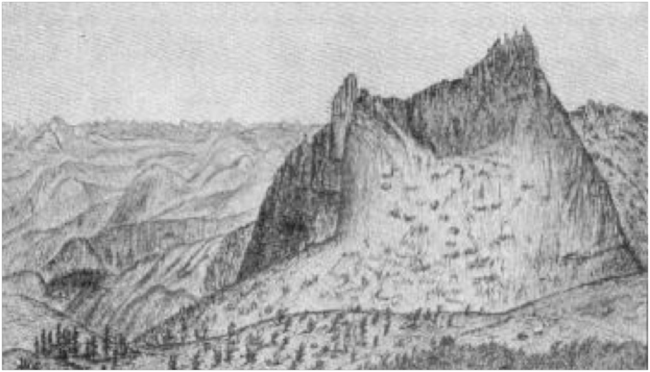

“September 7. Left camp at daybreak and made direct for Cathedral Peak, intending to strike eastward and southward from that point among the peaks and ridges at the heads of the Tuolumne, Merced, and San Joaquin Rivers. Down through the pine woods I made my way, across the Tuolumne River and meadows, and up the heavily timbered slope forming the south boundary of the upper Tuolumne basin, along the east side of Cathedral Peak, and up to its topmost spire, which I reached at noon…” Indeed, on that day in 1869, Muir made the first recorded ascent of Cathedral Peak, only one year after he arrived in California.

We cut off the main trail that now bears his name onto the climbing access trail for Cathedral Peak, and followed the small stream coming out of Budd Lake.

Muir wrote: “The dark heath-like growth on the Cathedral roof I found to be dwarf snow-pressed albicaulis pine, about three or four feet high, but very old looking. Many of them are bearing cones, and the noisy Clarke crow is eating the seeds, using his long bill like a woodpecker in digging them out of the cones.” As we ate lunch at Budd Lake, Clark’s nutcrackers, as they are now called – named after William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, who first described them – were noisy and active, starting the season of harvesting and caching the seeds of the whitebark pine, Pinus albicaulis, which is often the dominant tree species here in this granite treeline habitat.

“No feature, however,” Muir continued, “of all the noble landscape as seen from here seems more wonderful than the Cathedral itself, a temple displaying Nature’s best masonry and sermons in stones. How often I have gazed at it from the tops of hills and ridges, and through openings in the forests on my many short excursions, devoutly wondering, admiring, longing! This I may say is the first time I have been at church in California, led here at last, every door graciously opened for the poor lonely worshiper. In our best times everything turns into religion, all the world seems a church and the mountains altars.”

Reading a passage like this it is impossible to understand Muir without knowing that he was raised in a very strict and conservative Christian family. His father Daniel turned from the harsh view of Calvinism that “everyone is born corrupt and sinful, predestined for hell, with no hope of redemption except that given by God to a select, undeserving few,” according to his biographer Donald Worster, to the even more radical views of Thomas Campbell, a Scottish Calvinist immigrant to Pennsylvania who would fit right in with the Christian conservative “tea party” ideology of today. His father took out his dark view of God’s will on his son John, with overwork and frequent beatings on their Wisconsin homestead. It isn’t hard to understand young John’s delight at finally escaping from that dark worldview to the free, non-judging, beautiful world of the mountains of California, which he called the “Range of Light”.

The evening after his first ascent of Cathedral Peak, Muir “Camped beside a little pool and a group of crinkled dwarf pines; and as I sit by the fire trying to write notes the shallow pool seems fathomless with the infinite starry heavens in it, while the onlooking rocks and trees, tiny shrubs and daisies and sedges, brought forward in the fire-glow, seem full of thought as if about to speak aloud and tell all their wild stories. A marvelously impressive meeting in which every one has something worth while to tell.” He places himself squarely and tenderly into the present moment, making himself part of a multi-species biotic community of equals.

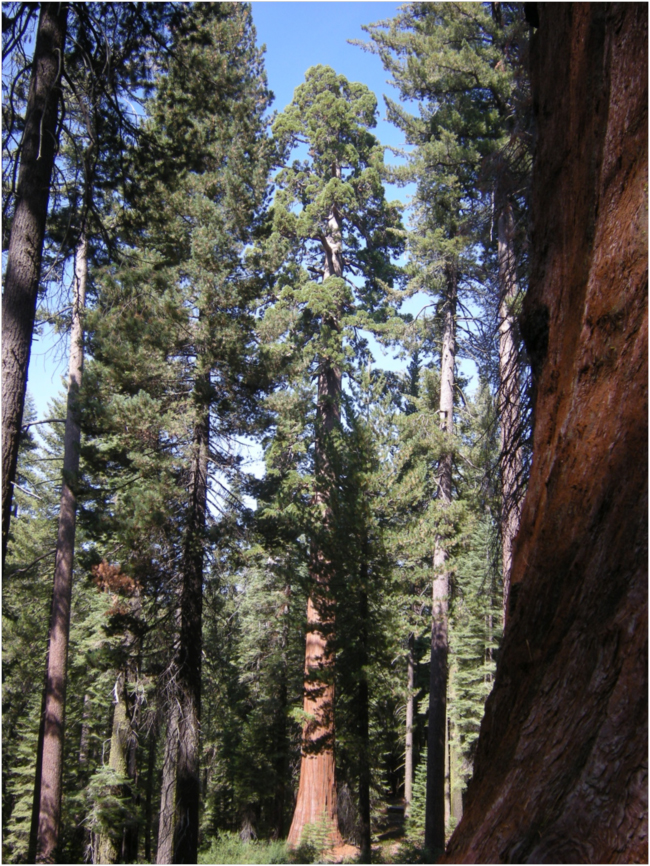

A year after climbing Cathedral Peak, in the autumn of 1870, Muir wrote to his friend and mentor Jeanne Carr, from Yosemite – which he called “Squirrelville, Sequoia Co.” – and gave the date as “Nuttime.” Mike Wurtz, curator of the Holt-Atherton Special Collections, pulled this letter from its file in the John Muir Papers when I was visiting there on August 14th, and we read it together. It was written in brown ink that Muir had made by steeping the bark of giant sequoia, Sequoiadendron giganteus. The letter is remarkable – playful, boyish, open and completely free and un-self-censored. Combined with his description of being “at church” on Cathedral Peak, it gives away how far Muir’s views of religion had evolved since the harsh Calvinist upbringing of his youth.

In the letter he wrote: “Some time ago I left all for Sequoia. I have been & am at his feet fasting & praying for light, for is he not the greatest light in the woods – in the world. … I’ve taken the sacrament with Douglass Squirrels, drunk Sequoia wine, Sequoia blood, & with its rosy purple drops I am writing this woody gospel letter. … I wish I was so drunk & sequoical that I could preach the green brown woods to all the juiceless world, descending from this divine wilderness like a John Baptist eating Douglass squirrel & wild honey or wild anything, crying, Repent for the Kingdom of Sequoia is at hand.”

This letter would be blasphemous if Muir really still had a shred of belief in the Christian tradition in which he was so strictly raised. He is humorously mocking, and clearly rejecting, that tradition in the letter.

In the introduction to the beautiful book of his woodblock prints, The High Sierra of California (with text from Gary Snyder) Tom Killion wrote: “Muir rose above scientific description and inquiry – though he was master of both – to achieve something that English-speaking Americans had been struggling to rediscover in themselves since they first set foot on the New World’s shores… the vision of God in Nature. …Through his vision, Muir not only gave utterance to a poetry of land and life rooted in the nature of the High Sierra, but also set in motion a cultural revolution in America’s relationship to wild nature – wilderness – that is one of civilization’s greatest hopes. … By the end of the century Muir was the champion of a movement claiming that wild nature demanded preservation not for its value as a future resource, but for its spiritual value to humanity. … Muir’s vision of the natural world is strikingly contemporary – a holistic vision of an intricately interconnected “Earth-Planet-Universe. It is also deeply spiritual and essentially pantheistic.”

Although most Muir biographers and scholars have been reluctant to say so, I think a fair interpretation of his writings and letters is that Muir had simply given up on the idea of “God,” and given up his Christian upbringing, and instead given his feeling of wonder and worship over to Nature. I’m not really sure this is “pantheism,” as Tom Killion calls it, because there is no “theism” involved. Nature is all there is, and completely enough.

For related stories see:

Related links:

- My First Summer in the Sierra, Chapter 10. 1911. John Muir.

- A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir. 2008. Donald Worster.

- Letter from John Muir to Jeanne Carr, Autumn 1870. John Muir Papers, Digital Collections, University of the Pacific, Stockton, CA.

- The High Sierra of California. 2005. Woodcut prints by Tom Killion, text by Gary Snyder.

September 22, 2014 10:13 am

Nice read, Bruce. Took me back to the first time I laid my very own eyes on Cathedral Peak in 1999.

September 23, 2014 8:09 am

Keep these coming Bruce. I always find myself filling in my understanding of the origins of conservation biology.

September 25, 2014 1:13 am

Bruce,

Nicely done. I hope you’re pleased with this offering that I found touching.