February 2018. After a hearty breakfast at the Skylight Diner, I went underground into Penn Station in midtown Manhattan and caught the C-line subway train heading uptown. New York City’s mind-boggling ethnic and cultural diversity and the New York Times kept me entertained during the half-hour ride to my rendezvous with John James Audubon. I emerged above ground at West 155th and Broadway on that cold morning, under a stratus sky of steel grey, and went to meet him, in spirit at least, at the Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum.

I’ve written before about Audubon. I’ve followed his footsteps in Pennsylvania, where he first encountered North American nature and met his future wife, and in Louisiana, where one of his most prolific periods of painting birds took place. Audubon’s life work became a foundation-stone of the conservation of biodiversity in America, and so we owe him a deep debt of gratitude. He lived a complicated, diverse and sometimes difficult life, making his achievements all the more notable. For the last ten years of his life, Audubon lived near where I had come up from subway at West 155th Street in what is now called the Washington Park neighborhood. To understand how this came to be at the end of his adventurous life, a bit of background is in order.

John James Audubon was born in 1785 in Haiti. He was raised in France, and first arrived in America in 1803 at the age of 18, sent by his father, an entrepreneurial French sea captain, to oversee the family’s lead mine at Mill Grove, Pennsylvania. The young Audubon instead roamed the nearby woods and fields from dawn to dusk, reveling in the wild, unfamiliar nature of this new world, observing, hunting, fishing, and collecting specimens. He was a gifted marksman, shooting birds that he then skinned and stuffed. He was also an artist, and he sketched those specimens. He met Lucy Bakewell, the daughter of the owner of the neighboring farm, who would become his wife. A good source for understanding Audubon is an excellent biography, Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America, by William Souder (2004).

Audubon’s life was so complicated and adventurous that it is impossible to summarize succinctly. After marrying Lucy, he moved west along the Ohio River, tried various business ventures along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, some less than successful, and landed finally in New Orleans. Throughout all of this, he carried an underlying obsession to paint all of America’s birds. I won’t even try to summarize here – read Souder’s biography.

In 1826 Audubon sailed for England, searching for an engraver with the skill to reproduce his pioneering avian art for sale to an upperclass audience for whom the biological diversity of their former colony was becoming a fascination. The Birds of America was first published by subscription on the largest sheets of paper available at the time, the huge format called the Double-Elephant-Folio. In 1838 the last five engraved plates were completed and printed, bringing the total to 435 species. After more than a decade spent in England and Scotland, Audubon finally returned to America in 1839. Almost immediately, he began to work with his son, John Woodhouse Audubon, and a lithographer and publisher in Philadelphia on a smaller and more affordable version of The Birds of America, seeking a wider audience at home.

Only then did Audubon finally feel he had the financial means to settle down. The family had been living in an apartment in New York City, but in 1841 he bought a 40-acre farm on the Hudson River in upper Manhattan, then a rural area some nine miles north of the city. He called it “Minnie’s Land,” using an endearing Scottish nickname for his wife Lucy, and they built a large house with a front porch facing the river.

But Audubon, always restless, soon went west in 1843 on an expedition to see and paint, leaving long-suffering Lucy at Minnie’s Land. He and his travelling companions made it as far as the mouth of the Yellowstone River on the upper Missouri. Audubon was then 58 years old. After eight months he returned to Minnie’s Land, having found 14 new species of birds to add to later editions of The Birds of America. He worked with his son John Woodhouse to bring out The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America – his illustrations of North American mammals – in three volumes between 1845 and 1848. But Audubon’s health and mental facilities declined rapidly after his return from the west. Some of his symptoms have been attributed to his lifelong exposure to arsenic, which he used as a preservative for bird skins. Audubon died in January 1851 at the age of 65 in his home by the Hudson, surrounded by his wife and sons. He was buried in the Trinity Church Cemetery, up on the bluff above Minnie’s Land.

Lucy Audubon continued to live in the house on the river. She outlived both of her sons, who died within a decade of their father. By 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, the profits from Audubon’s life work were exhausted, and Lucy had to sell Minnie’s Land. She moved into a boardinghouse in Washington Heights. She also sold the 435 watercolor original paintings for The Birds of America to the New York Historical Society for $4,000. It was a large sum in that day, which the Society struggled to raise from among its patrons. Finally, in her eighties and with her health declining, Lucy moved to Louisville, Kentucky, to live with relatives. She died there at 87; her body was sent by train to New York, and her ashes were buried next to Audubon in Trinity Church Cemetery. The house facing the Hudson was demolished in 1931, and “Minnie’s Land” is now only a memory.

——-

Because of their acquisition of Audubon’s original paintings in 1863 and later related acquisitions, the New York Historical Society now has the largest holdings of Audubon-related material in the world. After visiting Audubon’s grave, I made my way there, again underground on the subway. Because exposure to light can destroy the delicate colors of Audubon’s original paintings, only a few are displayed at one time, rotating through the Historical Society Museum’s Audubon “niche” every three months. February’s offerings were his original studies of two of the 435 species in The Birds of America, the Purple Finch and House Wren. The original studies, using watercolor over black ink and sometimes with other media, were used by the master-engraver Thomas Havell, in London, to produce the plates for the Double-Elephant-Folio edition ofThe Birds of America. Displayed alongside these original studies were the resulting prints, both from the Double-Elephant-Folio and from the smaller and less expensive “octavo” edition, aimed at a broader American audience, that was later printed in Philadelphia.

It was a delight to be able to see these examples from the New York Historical Society’s collection. They allow us all to see how Audubon saw and portrayed these birds. He painted a gregarious group of Purple Finches on the branches of a larch tree, indicating something about both their behavior and ecology. His whimsical portrait of a House Wren family, with a parent feeding a spider to gaping babies in a nest built in an old hat hung on a branch, is an ethological study in art. Ethology is the study of animal behavior, and here Audubon was indicating both the comfortable relationship the House Wren has with humans and also presenting information about its diet. His genius was to make birds come alive by showing not only their shapes and colors, but something of their ecology and behavior. For that reason – as I’ve written about here before – I think Audubon deserves to be considered the first “ecological” artist.

Audubon’s original study of the Purple Finch (Haemorhous purpureus) for engraving by Havell, 1824. New York Historical Society, February 2018

House Wren (Troglodytes aedon), study for engraving by Havell, original circa 1812 painted in Pennsylvania, New York Historical Society, February 2018

——-

Audubon’s life project was to paint all of America’s native birds. During my February “birding” trip to Manhattan I saw not a single one. I did see three bird species: the House Sparrow, sometimes called the English Sparrow (Passer domesticus); the Pigeon, or Rock Dove (Columba livia); and the Common Starling (Sturnus vulgaris). All are Old World birds, aggressively adapted to coexist with humans. When they made it to North America by hook or by crook, they became survivors and thrivers in the New World of New York City and on a new continent – just as all of the cultural and ethnic immigrants of our own species, including my Irish ancestors, have done. The stories of how these invasive avian immigrants came to America are diverse. For example, starlings were deliberately brought to the United States in 1890 by an organization dedicated to introducing every bird species mentioned in the plays of William Shakespeare. Approximately 60 Starlings were released in Central Park in New York City in 1890, and the population of this species is now estimated at 150 million, with a range from Alaska and Canada to Central America. The House Sparrow and Pigeon have their own stories.

——-

Back in Audubon’s old neighborhood near Trinity Church, his memory lives on in an artistic accolade, the Audubon Mural Project. After visiting his grave, I wandered the wintery streets of Washington Park, and the birds of America swooped across the sides of old brick buildings, stared from walls beside convenience stores, and flashed their colors from doorways along alleys. This project was the inspiration of Avi Gitler, owner of an art gallery in the Washington Park neighborhood, and his initiative was soon joined with support from the National Audubon Society. Please have a look at the Audubon Mural Project Map, an interactive map in Google Maps that is a work of info-art in its own right. Around 80 bird species have now been painted in and around Audubon’s old neighborhood, and the goal of the Audubon Mural Project is to paint all 314 species of North American birds that an Audubon Society study found to be threatened by human-induced climate change.

Before I ducked into the Taszo Espresso Bar to warm up with a cappuccino and an almond croissant, I’d spotted 20 species of the birds of America – not bad for a morning bird walk in February, and I didn’t even bring – or need – my binoculars! I could hardly stop a deep smile as I thought of how Audubon and his vision live on, even here in upper Manhattan. My rendezvous with his spirit and with his living legacy on that cold February morning gave me a lot of hope.

For related stories see:

- The Astonishing World Under the Sky: Wandering with John James Audubon in Louisiana Woods. December 2016.

- The Art of Ecology: Audubon’s Oystercatchers and Other Examples. November 2014.

- Visiting Revolutionary Ecological Relatives in Philadelphia. July 2012.

Sources and related links:

- Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America, by William Souder, 2004. Milkweed Editions.

- Birds of America. John James Audubon.

- Minnie’s Land

- Lithograph of Audubon’s House at Minnie’s Land: ”The Audubon Estate on the Banks of the Hudson.”

- The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America

- New York Historical Society. John James Audubon Collections.

- Audubon’s Aviary. New York Historical Society.

- The Audubon Mural Project

- The Audubon Mural Project. Gitler & Gallery

- Audubon Mural Project Map. Interactive map in Google Maps.

- Public Art Takes Flight. New York Times, 24 October 2017.

- Taszo Espresso Bar, Washington Heights, New York, NY

March 30, 2018 3:56 pm

One of your best, Bruce. Great photos. I love the house wren engraving, and all the murals.

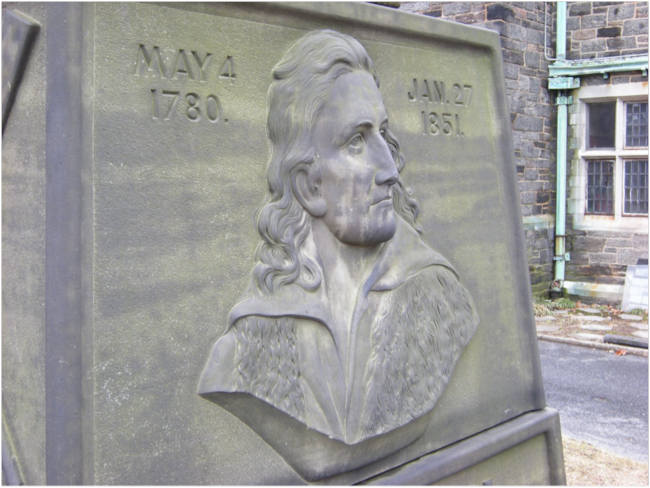

One issue — you write that Audubon died at age 65. His grave stone indicates 71.

April 7, 2018 2:34 pm

Rich,

I’m glad you enjoyed this piece! And complements on your sharp eye in catching the discrepancy between the date of his birth given on his grave monument, and all other sources. I had noticed that also, and posted the story anyway, not expecting anyone to “catch” the discrepancy. But… this is a mystery waiting to be investigated and solved.

Every source I’ve checked says that Audubon was born in 1785. Wikipedia says his dates were April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851, for example. The grave monument in the Trinity Church Cemetery with the dates you noticed was dedicated 42 years after his death. A brass plaque on the base of the monument says:

ERECTED

TO THE MEMORY OF

JOHN JAMES AUDUBON.

IN THE YEAR 1893.

BY SUBSCRIPTIONS RAISED

BY THE

NEW YORK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

A source for the history of Audubon’s grave, http://www.10000birds.com/audubons-grave.htm, says: “For forty years after Audubon’s death, which occurred in 1851, the only marker on his grave was a simple stone that said “Audubon.” Eventually, in the 1880’s, Professor Thomas Egleston, a member of The New York Academy of Sciences, learned that Audubon’s grave might be threatened by the extension of a street. He convinced the church to move Audubon’s grave and in return offered to lead the fund raising for a monument suitable to one of Audubon’s stature. Egleston, in his eventual position of chairman of the committee charged with getting the monument built, rallied the scientific organizations of New York City and beyond, many of whom apparently agreed that leaving such a prominent naturalist without a proper monument was simply wrong.”

Somehow, I guess, The New York Academy of Sciences must have gotten it wrong. Or perhaps there is another explanation waiting to be uncovered. Audubon himself is said to have sometimes claimed that he was born on a plantation in Louisiana, apparently to hide some of the facts surrounding his birth – in Haiti, to the mistress of a French sea captain and planter who already had a family in France. More research will be needed to figure out the reason for this discrepancy in birth dates!