April 2018. In 1836, Thomas Cole completed one of his most famous paintings, “View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm —The Oxbow.” That same year, Ralph Waldo Emerson’s groundbreaking transcendentalist essay, “Nature,” was published, and Henry David Thoreau, Emerson’s protégé, was in his junior year at Harvard. Charles Darwin returned from his five-year voyage on HMS Beagle, bringing the seeds of his radically new ideas about species and evolution. Andrew Jackson, known for his imperial style of governing and for his support for slavery and for the removal of Native Americans from their traditional lands, was president of the United States. Cole hated Jackson and mocked him in another of his famous paintings, The Consummation of Empire, the third in his five-painting series The Course of Empire, which he also completed in 1836. Perhaps tellingly, Jackson is revered by our current president.

View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow (1836). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

That same year, 1836, Cole’s “Essay on American Scenery,” a manifesto for why art matters to politics and economics, was published in the American Monthly magazine. Cole had a lot to say to his fellow Americans of the day, including:

“In this age, when a meager utilitarianism seems ready to absorb every feeling and sentiment, and what is sometimes called improvement in its march makes us fear that the bright and tender flowers of the imagination shall all be crushed beneath its iron tramp, it would be well to cultivate the oasis that yet remains to us, and thus preserve the germs of a future and a purer system. The pleasures of the imagination, among which the love of scenery holds a conspicuous place, will alone temper the harshness of such a state; and, like the atmosphere that softens the most rugged forms of the landscape, cast a veil of tender beauty over the asperities of life.”

Asperities? I had to google the definition, but in doing so found that Cole taught me a new old word for our current Trumpian moment: according to Merriam-Webster, “asperities” means “roughness of manner or of temper: harshness of behavior or speech that expresses bitterness or anger.” So, according to Cole, “the love of scenery” is going to help me – and all of us I hope – get through this moment of severe ASPERITIES in our lives!

I had a chance to see Cole’s painting The Oxbow on a recent visit to a special exhibition of his work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which I wrote about then. Looking out over the Connecticut River, Cole’s allegorical painting presents a stark contrast between wild and domesticated, forest and fields, the old American wilderness and the rapidly expanding domination of it by economic and political forces. The large painting, about four feet tall and six wide, shows a sinuous oxbow bend in the river. On the far side of the river, the forest has been mostly cleared for farms, and clear-cuts and wisps of smoke on the hills show that the process is continuing. On the near side, intact forest still covers the ridge, with dark rain falling in the background. Cole painted a tiny self-portrait into this painting, in the bottom center foreground, sitting at his easel but facing toward us, and, apparently, the wilderness. A plein air oil sketch on which it was based is itself a masterpiece of landscape art.

Cole’s plein air “sketch” for his later studio painting, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm – The Oxbow (1836). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

A comment from a friend in response to my essay describing the Cole special exhibition at The Met tempted me to try to revisit the spot from which Cole painted The Oxbow, to see what had changed in 182 years. After spending the night in Hadley, Massachusetts, and a hearty breakfast at The Stables, a highly-recommended local café, I drove about twenty miles south to Skinner State Park, managed by the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, which protects the ridge along which Mt. Holyoke lies. On this cool Monday morning in April the gate to the summit road was locked and there were only a few other cars at the trailhead. I started out with warm layers and a fleece hat and gloves, but soon had to shed them as the climb warmed me up. The trail switchbacked up the shady northfacing slope through a forest of eastern hemlock, white pine, beech, birch, and maple. In less than 1,000 vertical feet I was at the top of a gap on the ridge, and the historic Summit House on the top of Mt. Holyoke loomed like a surreal white spaceship just a few hundred feet farther up to the east. It was a glorious sunny spring morning, but I had to put my warm layers back on as a brisk west wind chilled my sweat from the climb.

So here – somewhere near here at least – was Cole’s famous view of the Connecticut River. But where, exactly? I had printed copies of both his plein air sketch and his final painting, hoping to use them to find the exact point-of-view of his paintings. One challenge was immediately clear from my view from the deck of the Mt. Holyoke Summit House: The river has shifted its course in the nearly two centuries since Cole saw it, abandoning the old oxbow and cutting a channel close to the flank of the Mt. Holyoke ridge. That geomorphological rearrangement was relatively easy to understand.

View of the Connecticut River from Mt. Holyoke, 23 April 2018. Lines show approximate position of the old oxbow in 1836.

But then there was a second challenge: Both Cole’s sketch and final studio painting show a somewhat ambiguous, dual viewpoint, which looks down at a ridge of rocks in the foreground where the artist has set up his easel. In the painting, Cole is barely visible, looking up at us from between those foreground rocks. The most logical guess would be that the view of the oxbow in the river was painted from the artist’s easel’s viewpoint. So, I took some photos from the deck of the Summit House, and then went to search for Cole’s ridge of rocks, which was not visible from there because of trees.

Down a steep flight of steps and short trail below the Summit House, maybe 100 feet down and 50 yards away, I found the rocks, now overgrown with trees. But if this was Cole’s view of the river, there was another challenge: The view was now obscured by trees. In Cole’s painting, some rough-cut stumps are shown in the foreground around the rocks, as if trees had been cut to clear the view of the river from above. Maybe then, but not now, his easel among the rocks was visible from the Mt. Holyoke summit.

But there is another hypothesis too. Whether the painting’s viewpoint was from the summit or his easel among the rocks below, Cole may have been “foreshortening” the view, imagining that he saw “The Oxbow” while riding on the back of one of the turkey vultures that was cruising the air currents above us on the day I was there. Or, maybe his view from his easel on the rocky ridge was really what he painted. Because of the trees that have grown in the ensuing 182 years it is impossible to confirm that now.

An interpretation offered by some art historians is that Cole, in his tiny self-portrait among the rocks, was depicting a moral choice, turning his back on the human modification of the landscape in the background and facing the wilderness in the foreground. But what was really going on? I never would have guessed without making this trip to Skinner State Park. The reality is that Cole perhaps was telling us a little white lie in order to make the point he wanted to make with this painting: From his easel among the rocks, Cole must have been looking up at the original Summit House on Mt. Holyoke.

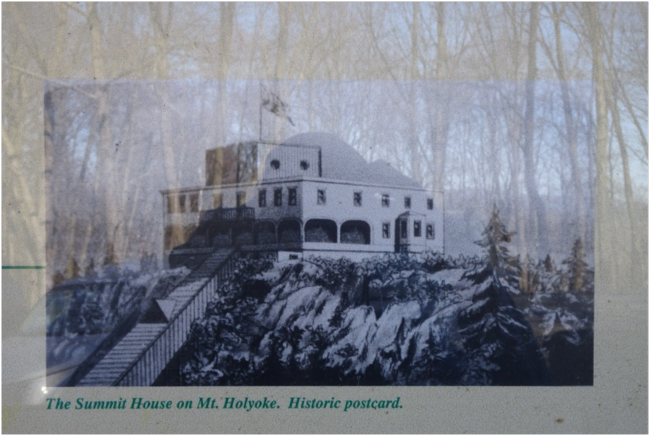

Historic postcard showing the Mt. Holyoke Summit House. Displayed at an informational kiosk, the photo also reflects the forest at the trailhead

Built in 1821, it was the first such facility for scenic landscape tourism in North America, according to an informational display at Skinner State Park. When Cole visited Mt. Holyoke from his home in Catskill, New York, on the Hudson River, less than 100 miles away, it was already a destination for tourists seeking grand views of “American scenery,” the aesthetic and spiritual values of which Cole extolled.

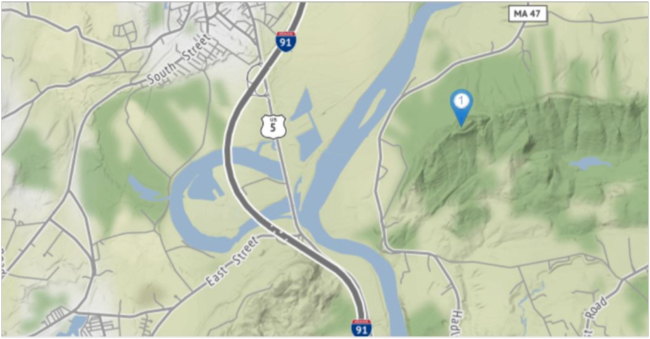

Now, “scenery” in this part of our continent may be an afterthought. From the Mt. Holyoke I could hear the constant hum of traffic on Interstate 91. I-91 cuts right through and across the old oxbow of Cole’s painting, carrying traffic and trucks from New Haven, Connecticut, through New Hampshire and Vermont to Quebec. I’d taken it myself the night before on my way to Hadley.

Location of Cole’s view of “The Oxbow,” indicated as point #1, on a map of roads and topography; I-91 cuts across the old oxbow. Source: Hudson River School Art Trail

What have we gained? What have we lost? Where are we going from here?

Pondering Cole’s painting is one way to help us think about those still-unanswered questions. Maybe, in salute of his premoniscient spirit in this anomalous Jacksonian moment in which we now find ourselves, we should let Cole have the last word, from his “Essay on American Scenery”:

“He who looks on nature with a loving eye, cannot move from his dwelling without the salutation of beauty; even in the city the deep blue sky and the drifting clouds appeal to him. And if to escape its turmoil–if only to obtain a free horizon, land and water in the play of light and shadow yields delight–let him be transported to those favored regions, where the features of the earth are more varied, or yet add the sunset, that wreath of glory daily bound around the world, and he, indeed, drinks from pleasure’s purest cup. The delight such a man experiences is not merely sensual, or selfish, that passes with the occasion leaving no trace behind; but in gazing on the pure creations of the Almighty, he feels a calm religious tone steal through his mind, and when he has turned to mingle with his fellow men, the chords which have been struck in that sweet communion cease not to vibrate.”

For related stories see:

- Another Conversation with Thomas Cole. February 2018.

- The Art of Ecology: Sketching with Cole and Church, May 2015.

- The Art of Ecology: Audubon’s Oystercatchers and Other Examples, November 2014.

- The Art of Ecology: A Pilgrimage to the Heart of the Andes, February 2015.

- In Search of the Sublime with Albert Bierstadt in Colorado, July 2015.

- Travels in Alaska: Seeking the Sublime Among Glaciers and Fjords, September 2015.

- In Search of the Sublime with Albert Bierstadt in Brooklyn, March 2016.

Sources and related links:

- View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow.

- Essay on American Scenery, Thomas Cole, American Monthly Magazine (January 1836)

- Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings. Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. January 30 – May 13, 2018.

- The Stables Restaurant, Hadley, Massachusetts

- Map of Joseph Allen Skinner State Park, Hadley, Massachusetts

- Re-examining Thomas Cole. Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser. January 9, 2018. The Magazine Antiques.

- Thomas Cole National Historic Site

- The Mt. Holyoke Summit House

- Thomas Cole Art Trail — location of “The Oxbow” viewpoint

May 15, 2018 12:37 pm

Bruce! A really lovely piece. Thank you for all your research, in the field and about Cole. Bravo.

Joan

May 26, 2018 4:30 pm

Thank you for the nice comment, Joan! I imagine the John Burroughs visited many of the same sites where Cole painted — Kaaterskill Falls, the Catskill Mountain House, and maybe even Mt. Holyoke — although I don’t know for sure. Do you?

After I climbed Mt. Holyoke, I went to Concord and Walden Pond, and will be writing some stories about that soon. John made what his biographer James Warren calls a “literary pilgrimage” to Concord and Walden in 1883 along with the editor of Century Magazine, and had a few interesting things to say about his trip. I’ll be “comparing notes” with him in one of my upcoming essays.

December 21, 2019 10:11 pm

Hey Bruce,

Great work! I was anxious to know if the view from the painting remained. You have done a great job in sating my curiosity.

Regards,

-Ali

January 30, 2020 4:53 pm

This is fantastic! I recently discovered this painting and I was trying to look up the view currently. Thanks for all the work you put into this. It must have been neat to find the little rock ridge depicted in the painting.