February 2016. It was Valentine’s Day, Sunday, February 14th, sunny and clear. But an Arctic blast on Saturday night had sent temperatures below zero in Central Park, making this the coldest Valentine’s Day in New York City on record and the coldest day recorded in NYC since 1994. Brrrrr! We took the subway from midtown Manhattan to Brooklyn to meet Albert Bierstadt.

Almost exactly one year ago I was in New York City, and took the opportunity to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see “The Heart of the Andes,” one of the grandest paintings by a key figure in the Hudson River School of American landscape painters, Frederic Edwin Church. I wrote about that quest, and its connection to Alexander von Humboldt, one of my heroes, in a story called “The Art of Ecology: A Pilgrimage to the Heart of the Andes.” On this frigid Valentine’s Day I was taking the opportunity to visit the Brooklyn Museum on a parallel pilgrimage, this time to see “A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie,” a grand landscape painting by Albert Bierstadt, another artist of the Hudson River School.

From the elevator lobby on the 5th Floor, Bierstadt’s huge canvas dominated the far wall of the gallery. We walked through three rooms and approached the painting, which was about seven feet tall and twelve feet wide. We stood back and appreciated its landscape-scale grandeur. From a distance the dramatic contrasts of light and form dominate one’s impressions of the work.

When other viewers moved on we stepped up to study the tiny details in the painting from a foot away. Up close, an encampment of tepees on a green meadow, invisible from a distance, brought humans into this grandiose scene. Bierstadt shared this technique of juxtaposing a landscape perspective and close-up detail with Frederic Church, who painted birds and flowers in the detailed foreground of “Heart of the Andes.” Bierstadt’s insertion of these Native Americans is interesting, because he didn’t see them in Colorado when he made sketches for this painting in 1863. In these imaginary details, he must have been trying to convey a nostalgia for the pre-European, Native American past, and the Romantic innocence it represented to the Hudson River School painters.

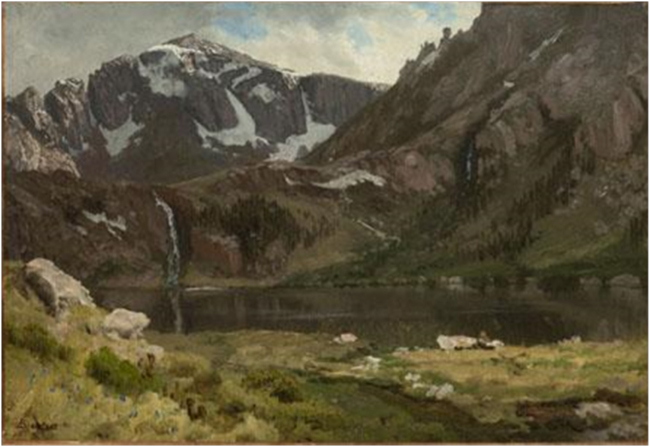

My Valentine’s Day quest to see this painting was also motivated by, and following up on, a trip to the Colorado Rockies last July, which I wrote about in a story I called “In Search of the Sublime with Albert Bierstadt in Colorado.” I described how Bierstadt was guided into the mountains west of Denver by an outdoorsman who also happened to be the editor of the Rocky Mountain News newspaper, William N. Byers. In that story I sketched the inconclusive evidence that William Byers, Bierstadt’s guide, was a distant ancestor of mine. And I described an oil sketch made in the field, “Mountain Lake,” now owned by the Denver Art Museum, which was one source for the dramatic painting I was looking at now in Brooklyn.

Just as we were lingering and studying Bierstadt’s painting, enjoying a lull in the flow of visitors, a special Valentine’s Day tour called “Love and Lust in American Art” swept through the gallery and stopped below the painting. The docent leading the tour of course told the romantic story of why this was a main stop on the “Love and Lust” tour.

In April of 1863, Bierstadt left New York with his friend, patron, and fellow explorer, Fitz Hugh Ludlow. Ludlow had become famous as the bestselling author of a countercultural book, The Hasheesh Eater, during a period of remarkable social change in New York and America, in some ways parallel to the post-WWII Beat era. He married Rosalie Osborne, only eighteen at the time, in 1859, against her mother’s advice. Bierstadt and Ludlow met Rosalie in St. Louis, Missouri, and she accompanied them as far as Atchison, Kansas, the starting point for the Overland Trail stagecoach, where the two men headed for Denver alone. After their extensive tour of the American west, Bierstadt returned with Ludlow to New York. By 1866 he had completed “A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie” from his Colorado sketches, in his studio in the famous Tenth Street Studio Building in Greenwich Village, where Frederic Church also had a studio. The mountain, previously unnamed, was named in the painting by Bierstadt for Rosalie, Ludlow’s wife. Rosalie had, in the meantime, divorced Ludlow. She married Bierstadt in November of 1866, a few months after the painting bearing her name was finished. His dramatic painting seems to express both the wild and dramatic summer storm that Bierstadt experienced at the lake below the mountain, and the sublime storm in his heart after meeting Rosalie Osborne.

With admission tickets to the museum on Valentine’s Day, visitors were given little cards with a red and white heart design that they could place below the painting that they “loved.” Bierstadt’s painting had more of these cards than any other painting on the American Art floor of the museum. The romantic love story lurking in the painting must have resonated with a lot of people on this cold Valentine’s Day.

Cards expressing votes for a “loved” painting below “A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie,” Brooklyn Museum, Valentine’s Day 2016

Bierstadt, like other Hudson River School painters, expressed the philosophy of Romanticism in the visual arts, as writers like Emerson and Thoreau did in literature. The Romantic painters of the Hudson River School brought an emotional, passionate dimension to the American relationship with the nature and landscapes of our continent. Their works expressed a love for the land, nature, and native peoples that Europeans had already, or were in the process of, dominating and destroying.

In the second volume of his great work Cosmos, Alexander von Humboldt included a chapter on the influence of landscape painting on the study of the natural world, and expressed his opinion that it ranked as one of the highest expressions of the love of nature. In his systems worldview, passed on to his disciples, including the Hudson River School painters, everything was connected – physically, geologically, ecologically, socially, politically, aesthetically, and emotionally. Living within that worldview, Albert Bierstadt had no trouble linking his love for the sublime wildness and grandeur of the Rocky Mountains to his feelings for Rosalie Osborne.

On an icy Valentine’s Day in Brooklyn that seemed to make perfect sense to me.

For related stories see:

- In Search of the Sublime with Albert Bierstadt in Colorado

- The Art of Ecology: A Pilgrimage to the Heart of the Andes

- The Art of Ecology: Sketching with Cole and Church

- The Art of Ecology: Audubon’s Oystercatchers and Other Examples

Sources and related links:

- Coldest Valentine’s Day in NYC on record as temperature drops to -1

- A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie. Albert Bierstadt. 1866. Brooklyn Museum.

- A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie

- Albert Bierstadt

- William Newton Byers

- Bierstadt’s Visit to Colorado: Sketching for the Famous Painting, “Storm in the Rocky Mountains.” By William Newton Byers. Magazine of Western History, Vol. XI, No. 3, January 1890.

- Get to Know: Albert Bierstadt’s Mountain Lake. Nicole A. Parks. 2013. Denver Art Museum.

- Tenth Street Studio Building, Greenwich Village, New York City

- Gallery Tour: “Love and Lust in American Art”