September 2015. All but one of the 40 glaciers that flow from the Harding Icefield, which caps the Kenai Mountains on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula, spill into a handful of fjords that connect with Resurrection Bay and the Gulf of Alaska. I had seen the only landlocked glacier in Kenai Fjords National Park, the Exit Glacier, on foot, as I described in a recent story about my September trip to Seward, Alaska. But I wanted to experience more of this spectacular country, so I signed up for day trip to Aialik Bay with Kenai Fjords Tours, one of the marine nature tourism companies operating out of Seward. Wednesday, September 16th dawned with some sunshine among the clouds over the ridges above town, although the forecast still called for a good chance of rain in the afternoon. We left the harbor at 11 AM on the 95-foot catamaran Aialik Voyager with almost 150 people on board, nearly full capacity. The diversity of my fellow passengers was striking: there were lots of foreigners, many Asian, and their ages ranged from babies and young parents to senior citizens. The ship’s captain and tour narrator was a women, Captain Reene Audette – “Ree-knee” was how she pronounced it.

We travelled down the east side of Resurrection Bay, surprisingly close up against the shore. This is a fjord landscape, carved by glaciers, and we were traversing along the cliff of an old glacial valley now half-flooded by the rising sea levels of the post-Pleistocene. Steep mountains rose above the waterline, and fell steeply down underwater, so we were in deep water very close to shore.

In a sunny cove the captain spotted a swirl of birds, feeding on a school of small fish below – “baitfish,” she called them. Suddenly a feeding humpback whale lunged to the surface, gulping the little fish, and probably a few birds, into its baleen-strainer mouth. We followed the whale up the cove for awhile, watching her blow and roll, and then spotted another feeding out in the channel toward Fox Island. We turned and followed that humpback for awhile also. Captain Reene described how the rich marine food chain of the area sustains the whales and birds, and the harbor seals, sea lions, and sea otters we also saw along this shore.

Just after noon we rounded Aialik Cape, and for half an hour were in the open Gulf of Alaska, the Aialik Voyager rolling with the big swells of the North Pacific, although it was a relatively calm day in the big ocean. Bright noon sun shone silver on the water. Then we cruised into Aialik Bay, another fjord, and passed Holgate Arm on the port side, where the Holgate Glacier spills into the ocean from the icefield above. There were more sea otters and humpback whales, and rafts of seabirds – horned puffins and common murres. We were heading for the Aialik Glacier, the main tidewater glacier entering this fjord at its upper end.

Finally at about 2:45 PM we approached the face of the glacier, where ancient ice met ocean. The ice front loomed above us, dwarfing the Aialik Voyager. The captain asked for everyone to be quiet in order to experience the glacier by listening as well as looking. And I was surprised that among this large, diverse crowd, people mostly did quiet down, listening and looking.

Every few minutes the glacier would give a sharp crack, like a rifle shot. Sometimes a cascade of falling ice would plunge into the water after such a sound, but sometimes not. Park regulations required the Aialik Voyager to stay a quarter-mile from the ice front. Even so, that glacier wall was so immense that if a large piece of ice had suddenly calved off, I wondered if we would be safe even at this distance.

I hadn’t expected it, but I found myself mesmerized and awed. Being so close to this huge, otherworldly mass of cracked and serrated blue ice was an emotionally powerful experience. In the bright sun the white surface of the glacier was intensely white. Where cracks and crevasses exposed the deep ice, it glowed with a surreal water-blue glow. I found it a very peaceful, astounding experience.

We stayed up against the ice wall for more than half an hour, and then motored slowly and quietly through the field of floating ice in front of it. The glacier chunks gave off a snap-crackle-pop sound in the water, as the air trapped in ancient snow, and then compressed into pressurized bubbles in the ice, finally melted out, just now, at this moment on this sunny afternoon, September 16th, in 2015.

I thought of another time I’d heard that sound of ancient air escaping from glacial ice into the present moment. It was under much different circumstances – my daughter’s wedding dinner. One invited guest worked for the U.S. National Ice Core Laboratory, based in Denver. Somehow – I didn’t want to ask how, it case government rules forbade it – he had brought to the after-dinner reception two pieces of ancient ice cores, one from Greenland, and one from Antarctica. The Antarctic ice, if I remember correctly, was from nearly a mile deep, and some pieces exploded like popcorn when unpacked, the ice core expert said. But splashed with Maker’s Mark that evening, the Antarctic ice whispered quietly in my glass like a memory of the snap-crackle-pop elves of a long-ago breakfast cereal, and I felt I was having a conversation with deep time. I had that same feeling motoring through the ice floes at Aialik Glacier, listening to their whispering.

After almost an hour hovering quietly along the ice front, Captain Reene took us away, heading back toward Seward. Rounding Aialik Point, with the big Pacific swells again rolling the boat, I was standing in a sunny corner of the deck out of the wind. The scenery was glorious, surprising, unpredictable: high island tops, once the tops of nunataks rising above the icefield; a fur of dark spruces climbing a steep slope to a ridge; mists and fogs pouring over glacier passes; birds hurrying off; patches of sun touching snow-covered ridges; more humpbacks, and dolphins. It was a day of being saturated with scenic beauty, like charging some kind of deep-brain battery that is fueled by visual landscapes.

Our ancestors spent hundreds of thousands of years wandering landscapes and paying close attention to all the details. Reading and navigating landscapes is probably one of the most important survival skills they needed in their travels. We love landscapes and their details – “scenery” – if you will. Some conservationists scorn the mentality that oriented our national parks generally to grand scenery, and not to “biodiversity.” They are narrow-minded in that regard, not only because of the importance of sublime scenery to our mental health and sense of the meaning of our lives as a human species, but also because “scenery” is the vessel that contains biological diversity.

——-

I’ve written before about Frederic E. Church, a central figure in the Hudson River School of American landscape painting, and his lifelong quest to capture the “sublime” in his art. In the summer of 1859, Church sailed north along the coast of the Canadian Maritime Provinces to the southeastern tip of Labrador, just a few months after he had unveiled his giant work, Heart of the Andes, with all of its tropical lushness, to great public acclaim in New York. During the six-week voyage Church made more than a hundred pencil and oil sketches of the effects of light on icebergs adrift from Greenland glaciers, and over the next five years turned them into studio works. Church tried to capture the luminous “sublime” shining from the transcendent, otherworldly ice. His iceberg paintings presented a striking contrast to the lush tropical world of Heart of the Andes, but Church was seeking an underlying unity in nature, the worldview of “cosmos” described by his great inspiration, the German explorer and scientist Alexander von Humboldt.

In that hour staring into the icy face of Aialik Glacier, I experienced the transcendent sublime that Church saw in the icebergs of Labrador.

——-

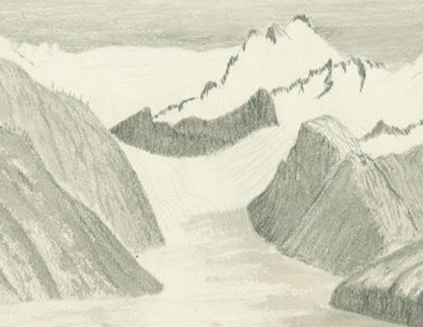

My trip to Alaska was a continuation of my previous journeys following in the footsteps of John Muir. Muir made seven trips to Alaska between 1879 and 1899. His journals contain dozens of sketches of glaciers and glacial scenery. He discovered the glacier in Glacier Bay now named for him on his first trip to Alaska in 1879. Muir’s investigations of active modern glaciers in Alaska supported his view that Yosemite was an ancient glacial landscape.

Detail from “View of one of the Tributaries of Muir Glacier from Tree Mountain.” Sketch by John Muir, circa 1895. Source: Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific, John Muir Drawings.

Travels in Alaska was Muir’s last book, based on his 1879, 1880, and 1890 trips to southeast Alaska. He was in the process of preparing it for publication when he died on Christmas Eve, 1914. It was published by Houghton Mifflin in 1915. In the first sentence of Chapter 2 Muir wrote: “To the lover of pure wildness Alaska is one of the most wonderful countries in the world. No excursion that I know of may be made into any other American wilderness where so marvelous an abundance of noble, newborn scenery is so charmingly brought to view…”

Muir’s seventh and last trip to Alaska was as a member of an expedition mounted in 1899 by E. H. Harriman, railroad magnate, one of the wealthiest men in America. Muir was one of a distinguished group of 23 scientists, photographers, artists, and writers invited aboard the steamship George W. Elder, which departed from Seattle on May 31, 1899. John Burroughs, a popular nature writer and friend of Muir’s, was the expedition’s official chronicler. Another of his fellow passengers was Edward S. Curtis, a photographer most known for his portraits of American Indians. Curtis took a number of photographs at the tidewater front of the Muir Glacier in Glacier Bay, including one of a member of the expedition in a canoe close to the ice front. Notes with the photograph say “just after this was taken a huge berg broke off almost swamping the canoe and washing overboard a series of very large negatives of the glacier front.” This suggests that Curtis himself was in another boat when taking the photo, but may also have experienced the sudden ice calving. I thought again of my hour at the Aialik Glacier front, glad that we hadn’t experienced a major calving event, which could easily have treated the Aialik Voyager like a tiny canoe.

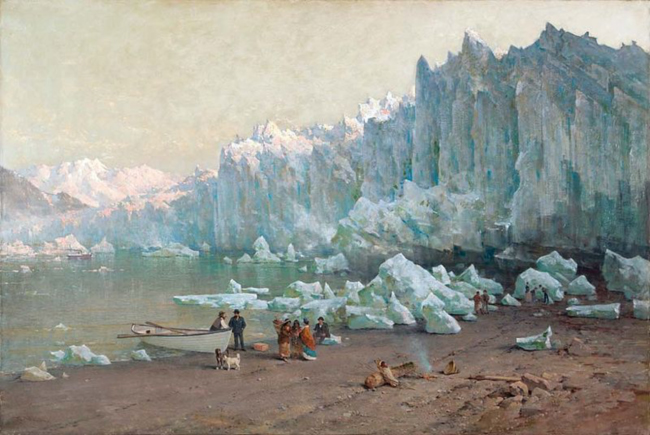

In about 1887, Muir commissioned his friend, California artist Thomas Hill (1829-1908), to paint the Muir Glacier, because he felt that Hill’s work could capture the shape, colors, and textures he observed. Hill was a painter loosely associated with the Hudson River School, who painted in New England, Yosemite, and Alaska. The Muir Glacier painting originally hung in the west parlor of the Muir home in Martinez, California, and is now owned by the Oakland Museum of Art. A colored half-tone of this painting was used on the cover of Muir’s book Travels in Alaska.

The intellectual and philosophical connection between John Muir and Frederic Church, and the Hudson River School of American landscape painting, was Alexander von Humboldt, the great German explorer, geographer, and scientist. Both men had oriented their lives based on Humboldt’s writings, and his systems-thinking-view of the Earth and life as “cosmos,” a holistic system in which everything was connected, with the whole greater than the sum of the parts. This was the early scientific foundation of ecology and other systems sciences. Church followed Humboldt’s footsteps to Ecuador and the Andes, and the coasts of Labrador, determined to capture his cosmic worldview in visual, aesthetic terms. Muir started to follow Humboldt to the Amazon, caught malaria in Florida in late 1867, ended up in California, and only finally went to South America to pick up Humboldt’s tracks again in 1911, at the age of 73 years old. Muir’s Humboldtianism took a scientific direction in his geological and glacier studies in California and Alaska, as well as a philosophical direction in his nature writing and conservation action.

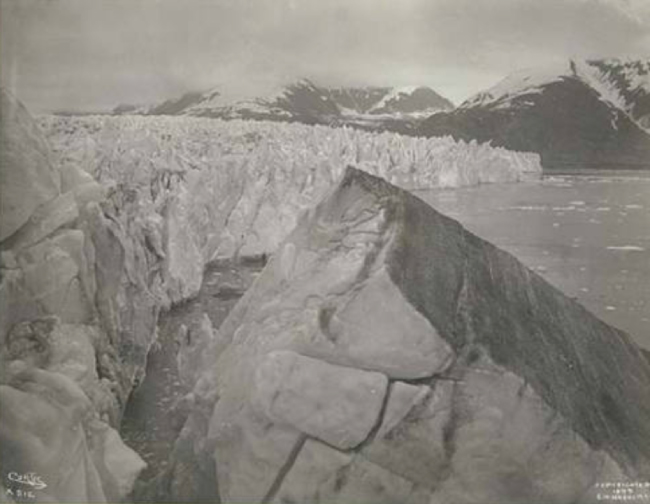

Thomas Hill’s painting of the Muir Glacier, and a historical photograph taken sometime in the 1880s, provide a striking visual contrast when compared with a 2005 photograph of the view from the same location. They echo my own personal “time series” of photographs of the Portage Glacier, which I used in my previous story about my recent travels in Alaska. The visual effect of the time-lapse comparison between the 1880s photo and painting of the Muir Glacier, and its condition in 2005, and my personal time-lapse photographic record of the Portage Glacier, are exactly parallel. In both cases, the dramatic retreat of the luminous glaciers and the iceless foregrounds of the current scenes create a lifeless, empty, sad feeling.

Muir Glacier, photo taken sometime in the 1880s. Source: USGS, Repeat Photography of Alaskan Glaciers

Rephotograph of Muir Glacier from the same location, 2005. Source: USGS, Repeat Photography of Alaskan Glaciers.

What’s that about, I wonder? Is there something in our deep Paleolithic brains that celebrates the sublime luminism of an icy world? After all, our species did “grow up” and come into its own, in part, in the ice age of the Pleistocene. We hunted mammoths and other big mammals along the edges of the continental ice sheets, and warmed by their furs and our fires, we talked and dreamed of the future. Maybe we remember that glacial scenery deep in our genetic unconscious, and revisiting it triggers the feeling of the sublime, the cosmos, connecting our inner and outer worlds in deep time. Maybe that explains why I was so moved and inspired by an hour spent up close to the Aialik Glacier. How will humans cope when we lose the ice?

For related stories see:

- Yosemite National Park: John Muir and Conservation Philosophy, Monitoring Glaciers, and Payments for Ecosystem Services. October 2011.

- All I Came to Seek I’ve Found: Closing the Loop with John Muir in Martinez. August 2014.

- The Art of Ecology: A Pilgrimage to the Heart of the Andes. February 2015.

- The Art of Ecology: Sketching with Cole and Church. May 2015.

- An Afternoon at Slabsides with John o’ the Birds. May 2015.

- In Search of the Sublime with Albert Bierstadt in Colorado. July 2015.

- Time Travels in Alaska. September 2015.

Sources and related links:

- Kenai Fjords National Park

- Kenai Fjords Tours

- Resurrection Bay information, Alaska Department of Fish and Game

- NOAA Cetacean survey in Gulf of Alaska

- U.S. National Ice Core Laboratory

- The Worlds of Frederic Edwin Church

- Frederic Edwin Church. 1863. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- In Search of Icebergs: Tracing the 1859 expedition of the painter Frederic Edwin Church to Newfoundland and Labrador. Barbara Matilsky. 2008.

- John Muir. Travels in Alaska. 1915.

- Muir Glacier, Alaska. National Snow and Ice Data Center.

- View of one of the Tributaries of Muir Glacier from Tree Mountain. Sketch by John Muir, circa 1895.

- Harriman Alaska Expedition of 1899. University of Washington Digital Collections.

- Muir Glacier, Alaska, June 1899.Photograph by Edward S. Curtis.

- Member of the Harriman Expedition canoeing in Glacier Bay, Muir Glacier, Alaska, June 1899.

- Thomas Hill

- Muir Glacier, Alaska. Painting by Thomas Hill 1887-88. Oakland Museum of Art.

- Muir Glacier, photo taken sometime in the 1880s. Source: USGS, Repeat Photography of Alaskan Glaciers.

- Rephotograph of Muir Glacier from the same location, 2005. Source: USGS, Repeat Photography of Alaskan Glaciers.