August 2014. Waiting in Buenos Aires for a ship that would take him to Africa, the second leg of the last major journey of his life, John Muir wrote to his friend Henry Fairfield Osborn in late November, 1911: “All I came to seek I’ve found and far, far more.” Muir’s words echoed in my head as I flew back east from a recent trip to California. “Me too,” I thought.

But what, exactly, was Muir seeking on that last journey of his, travelling alone, at the age of 73? We will never know for sure, because he died only a few years later, before he wrote or published anything about it. We know he made a long trip to central Chile in search of forests of Araucaria araucana, the monkey puzzle tree. But we can only guess from his sparse travel journal and correspondence from the trip why those trees fascinated him so much.

Araucaria araucana on the ridge Muir traversed in 1911 near Volcán Tolhuaca, Chile (photo taken in 2013)

And what was I seeking on my trip to California? One goal was to close a loop with Muir. In 2012 and 2013 my son Jonathan and I had retraced Muir’s exact route to the site where he camped and sketched in a monkey puzzle forest in Chile in 1911. I wanted to visit his California home in Martinez, and to see and hold his journals and letters. Somehow I thought this would help deepen my understanding of this inspiring episode in Muir’s amazing life, and my serendipitous connection with it.

To reconstruct Muir’s route in Chile, we had gotten help from the staff of the John Muir Papers, housed in the Holt-Atherton Special Collections at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, and also from the archivist at the John Muir National Historic Site in Martinez. When I let them know that I would be in California in August for the Ecological Society of America’s annual meeting, both of those institutions arranged presentations about our rediscovery of Muir’s route to the Araucaria forests.

On a sunny Wednesday morning I blasted down the I-80 from Sacramento in my black Hyundai Sonata rental car, turned off on I-680, and crossed the high freeway bridge across Carquinez Strait from the north. Following directions from Google Maps, I exited just across the bridge, swirled around the big Shell oil refinery on Shell Avenue, and popped out in downtown Martinez.

Rumor has it that the martini may be named after Muir’s hometown. I didn’t try to pursue that historical thread, but instead bought a big turkey sandwich at Luigi’s Deli on Main Street, and drove up Alhambra Avenue to the John Muir National Historic Site, where I ate under a small grove of coast redwoods behind the old historic Strenzel-Muir House. After lunch I headed out on the trail up Mount Wanda, one of the rolling coastal hills in this area, now part of the National Historic Site. This was where John walked with his daughters – Wanda, the eldest, and Helen, her younger sister. The afternoon was sunny and hot, but with the dry heat of the west, not really unpleasant in the shade and with a bit of a breeze. A local freeway, the “John Muir Parkway,” now passes between the historic house and Mount Wanda, and the parking lot for the trail was just beside it. The traffic noise gradually gave way to peace and quiet as the trail wound around the mountain. Some views from the trail were vistas of golden grass and dark green live oaks, probably very similar to those of Muir’s day. Other views were of oil refineries and freeway bridges, stark reminders of a century of dramatic changes here at the home base of one of the world’s most articulate advocates for wilderness. I was enjoying the schizophrenia, in a certain way; I knew that later, in Yosemite, I would have a chance to visit some of Muir’s old wilderness haunts.

After a mellow hike to the top of Mount Wanda and the nearby, slightly lesser, hilltop called Mount Helen, after Muir’s youngest daughter, I returned to the historic Strenzel-Muir House. I was treated to a private behind-the-scenes tour, from basement to attic, by Eric Stearns, one of the senior National Park Service interpretive staff. This was a grand house in Muir’s day, built with the substantial wealth accumulated by his wife’s father, John Strenzel, from his Martinez medical practice and large fruit orchards. The 10,000 square foot house was built in 1882, with all the modern conveniences of the day, including gas lighting, coal burning fireplaces, flush toilets, and a telephone. When her husband died in 1890, Mrs. Strenzel invited her daughter Louie, John, and their two young daughters to share the big house with her.

Late afternoon sunshine streamed into Muir’s study on the second floor of the house, where he worked and wrote – he called it his “scribble den.” The floor was strewn with drawings, papers, and piles of books. Pine cones sat on windowsills with pieces of petrified wood. The look of productive, working chaos must have been deliberately preserved. It felt familiar – I left my office looking very much the same way before this trip.

Toward the end of the tour we climbed up into the bell tower, from which a bell had signaled to the workers scattered in the orchards around the house: time to start, break for lunch, start again, quit for the day. And, according to Eric, Muir’s wife Louie may have used a special ring of the bell to call John back from his ramblings or reveries when he was late for dinner. Eric suggested I try ringing the bell, so I did: “John, are you coming?”

After the tour the NPS staff set up chairs and a digital projector in the main living room downstairs, and a small crowd of local volunteers and Muir enthusiasts gathered to listen to my presentation about his quest to see the monkey puzzle forests of Chile on his last journey. Throughout the evening I had the feeling that Muir’s spirit was listening down the stairs from the scribble den, smiling a small contented smile, and perhaps wondering what was so intriguing to people living now about his trip to see Araucarias on the volcanoes of Chile.

The next day I was off on another Muir exploration, still trying to “close the loop” – this time to meet the staff of the Holt-Atherton Special Collections at the University of the Pacific, where the John Muir Papers are housed. Jonathan and I had used high resolution digital copies of the relevant pages from Muir’s South American journal, obtained from this archive, to follow the clues from his entries and sketches, and reconstruct his route to the site where he camped under a canopy of monkey puzzles.

After a late morning presentation to a small group of University of the Pacific faculty, and lunch on the balcony of the faculty club overlooking the Calaveras River, the curator of the Holt-Atherton Special Collections, Mike Wurtz, took me into the climate-controlled inner sanctum of the John Muir Papers in the basement of the Holt Library. He described the collections they hold and the history of their acquisition of this amazing resource, then showed me several of his favorite letters from Muir’s correspondence, including a delightful letter from John to his friend and mentor Jean Carr, written in brown ink extracted from the bark of a giant sequoia.

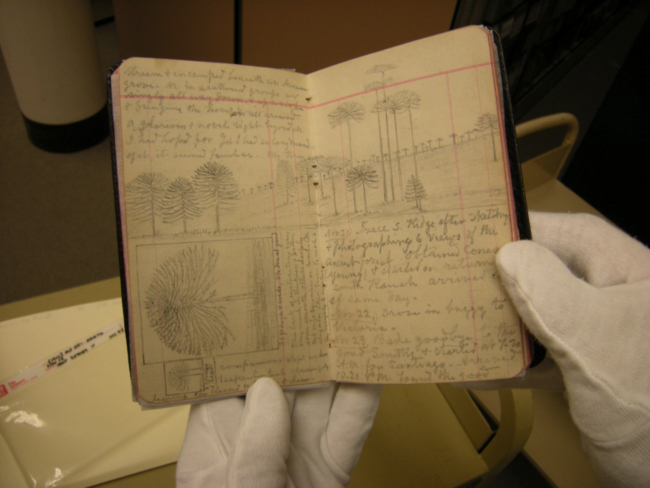

Then came the highlight of the visit. From a file Mike pulled “Journal 77,” from November 1911, and handed it to me. This was the very journal in which Muir described his quest for the monkey puzzle forests and sketched the trees – the journal from which we had followed his footsteps. But it was so small! It was barely a palm wide and a hand tall – maybe 3-1/2 by 5 inches. We had printed the digital copies that guided us on our search on 8-1/2 by 11 paper, and were imagining Muir’s sketches at that scale. But they were much smaller, in reality, and his writing much smaller, making the level of detail he obtained all the more remarkable. He must have kept his pencil sharp.

Holding Muir’s Chile journal with sketches of Araucaria araucana (photo used with permission of Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific)

Holding the journal, so small in my cotton-gloved hands, and looking at Muir’s original sketch of the Araucarias we saw a hundred years later, the loop closed. All I came to seek I found. And much that I never imagined, I found too.

For related stories see:

- Tracking John Muir to the Monkey Puzzle Forests of Chile

- Maples, Mapuches, and Monkey Puzzles: Human Dimensions of John Muir’s Travels in Chile

- Following Muir’s Route in Sketches and Photos

- Documenting Forest Change at the Muir Site

Related links:

September 6, 2014 11:48 pm

Pretty neat photo of his field notebook. Quite a nice rendering of Auracaria auracana. Thanks for including the photo and description — clearly, being a naturalist in those days meant being quite a good illustrator, and having a sharp pencil handy (and a sharpener of some sort).

When I did forest surveying (for a short time before enlisting in the Navy), we taped a piece of sandpaper onto the back cover of our field notes to sharpen pencils — or we carried a small wooden “sandpaper lead pointer”. I used it (and a jackknife) in field work in Tibet and India. I wonder if Muir carried one around with him.

Thanks again for a nice article, Bruce,

Rich

September 8, 2014 2:38 pm

Thanks for this Bruce… Nice to be reminded how “Muir” and “Wonder” become synonyms..

Hope to cross paths again…

Scott