After a sunset touchdown in Anchorage, I spent Saturday night in the Puffin Inn, a two-star motel, and after a two-star high-calorie breakfast at Gywnnie’s Old Alaska Restaurant just up the street the next morning, I was finally driving south toward Seward on a sunny Sunday morning. Whew! I was glad to escape Alaska’s big city, after my escape from Washington, DC, yesterday.

But I was soon delayed along the eastern shore of Turnagain Arm when I saw lots of cars pulled off at a turnout with a sign that said “Beluga Point.” Hmmm, I thought – I didn’t know there could be belugas here. I stopped, scanned the water for a few minutes, saw nothing, and drove on. A little farther south at a small turnout a few carloads of people were looking and pointing offshore. I ignored them, but around the next bend a flash of white on the water caught my eye – a white shape like a small iceberg appeared, then in a blink was gone. I did a U-turn, and went back up the road. Sure enough, a pod of belugas was making its way north alongshore against the incoming tide, and among grey calves and subadults a few iceberg-white adults surfaced occasionally. Belugas! I never saw a beluga before, and never imagined I would see one.

The beluga whale, Delphinapterus leucas, is a toothed whale with a circumpolar distribution in the Arctic and sub-Arctic. Belugas in the Gulf of Alaska and Hudson Bay are the southernmost populations of this species in the North American sub-Arctic. Two geographically-isolated populations are still hanging on even farther south, one in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Quebec, and one in Cook Inlet, the channel that flows from Anchorage to the Gulf of Alaska. They are essentially relict populations, cut off from breeding with other belugas when climate change began to reduce the ocean area where glaciers once poured from icefields and calved icebergs into the icy waters. In 2008, the Cook Inlet beluga population, which fell to a low of 278 in 2005 from 653 in 1994, was determined to be at risk of extinction and listed for strict protection under the U.S. Endangered Species Act by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which is in charge of ESA listings for marine mammals. NOAA was scolded by Sarah Palin, then Alaska’s governor and candidate for vice-president, who called the listing “premature.” It was these Palin-defying Endangered Species Act belugas that welcomed me to Alaska.

——-

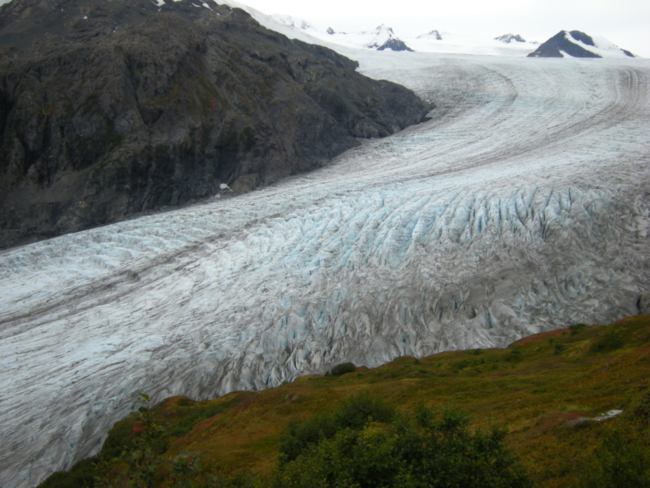

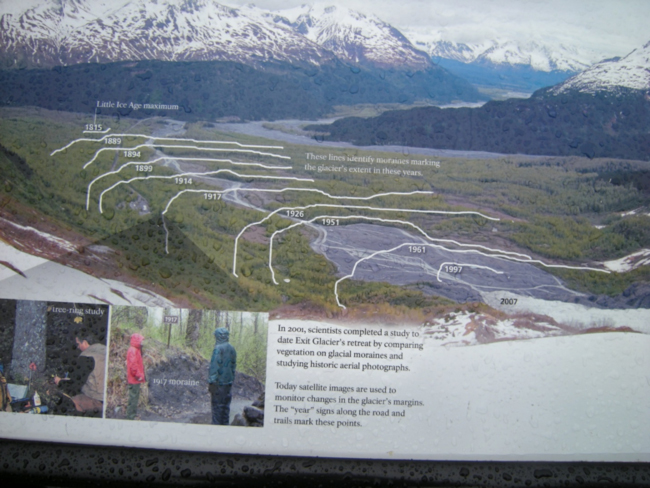

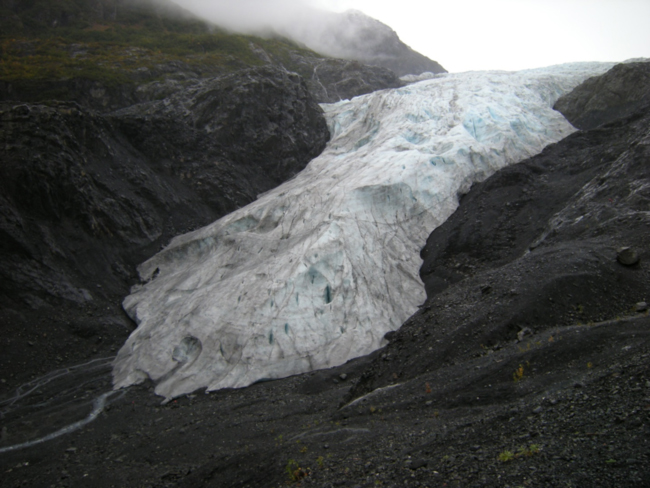

After that unexpected, once-in-a-lifetime distraction, I pressed on to Seward to meet up with my son Jonathan, who was working at Kenai Fjords National Park as a seasonal science research assistant. We ate a lunch of local salmon he had caught, and drove to the visitor center and trailhead for the Exit Glacier, the only one of Kenai Fjord’s 40 glaciers that is accessible to land-based visitors. The sunny day had become an overcast afternoon. We hiked up to the Top of the Cliffs, a viewpoint about halfway up to rim of the Harding Icefield, from which the Exit Glacier starts as a river of ice spilling down a valley. It was a fast climb on a steep, switchbacked trail for two and a half miles through spruce, black cottonwood, and alder. We passed above treeline at about 2,500 feet to a grand view down the Exit Glacier’s wide old valley and across its braided outwash plain toward Resurrection Bay and the mountains beyond. The terminus, or toe, of the glacier was far below. Beside us it flowed over a hidden bedrock cliff, breaking into a cascade of blue crevasses.

——-

I had been to Seward once before, when I was 12 years old. My family took a long summer trip to Alaska from northern New Mexico where we lived because my dad wanted to revisit the place where he had been stationed in the early years of World War II. When Pearl Harbor abruptly altered his plans, my Iowa-farm-boy father was a graduate student in the Physics Department at Oregon State University, but also a captain in the Army ROTC. Within a few months, in April, 1942, he found himself in a log cabin across Resurrection Bay from Seward. His gang of guys were in charge of a small gun emplacement that was supposed to defend that northernmost ice-free port in the United States from a possible Japanese attack. They did their best to keep warm, and as spring came and the snows melted they began to explore the mountains nearby, hiking up to glaciers and shooting white mountain goats with their army rifles. By summer they were wading into Fourth of July Creek to grab spawning salmon with their bare hands. My dad’s stories always made it sound like his war years in Alaska were some of the best years of his life.

So to refuel his memories, my dad drove the family north up the old Alaska Highway in a 1962 Chevrolet Greenbrier van outfitted for camping to revisit his old haunts. We went to Seward, and on a long bright summer day we drove as far as we could around the head of Resurrection Bay, then hiked to the mouth of Fourth of July Creek. As I remember it now, we didn’t find his old cabin, but we did find some old sandbags on the beach where the gun emplacement had been. A few old Kodachrome slides from that trip partially confirm my memories.

Of course one of my missions with my son was to try to find the site of my dad’s cabin, and where I’d been with my family in 1963. Rephotography is a modern tool for time travel, and we wanted to use it if we could.

It is amazing how it is possible to hold an old photograph and navigate to almost the exact spot where it was taken by comparing features in the foreground and distance. We did that with my dad’s photo of his cabin from 1942, and found ourselves on a steep gravelly beach looking toward the same peaks in the background. But the mouth of Fourth of July Creek where my dad’s cabin stood is now a marine industrial area, and Royal Dutch Shell has a facility there where it can transport offshore drilling rigs to the Arctic Ocean. A marine oil-drilling rig was here now, docked in the foreground, hissing and humming from some mysterious internal processes. Whether it was waiting to go north, or being repaired or refurbished from a drilling foray earlier in the summer, we couldn’t guess.

In July, the Obama administration gave conditional approval to allow Shell to begin exploratory drilling in the Chukchi Sea, about 140 miles from Alaska’s northwest coast. The approval represented a significant loss for environmental organizations, which have argued against Arctic drilling because of concerns over impacts on vulnerable animal species like belugas, polar bears, and walruses, and also because oil extraction from the Arctic will only feed the climate change that is affecting it.

I had a memory of visiting Portage Glacier, on the road from Anchorage to Seward, with my family in 1963: a cold grey day, clouds hanging over the mountains, standing on a gravel beach by a lake full of icebergs you could almost reach out and touch. Another old slide confirms the memory.

So of course, in the interest of time travel, I stopped at Portage Glacier again on my recent trip. It was a stunning change. The glacier had retreated miles, and its terminus was far above the lake it used to fill with icebergs. The empty, sad, icebergless lake seemed to mock my memory.

——-

I didn’t know until it emerged in my ecological mind that there was a personal link between these old photos showing climate change in my lifetime and my recent reading of Reason in a Dark Time, a thought-provoking book by Dale Jamieson. The provocative subtitle of the book is: Why the Struggle Against Climate Change Failed – And What It Means for Our Future. I bought it after hearing Dale speak at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in April. It languished in a pile of other to-be-reads until I took it with me to Alaska, and read almost half of it during the flights from Washington to Anchorage, which took most of a day. My reading of Jamieson’s book and my trip to Alaska intersected to reveal meanings I hadn’t imagined.

Atmospheric scientists began warning in the late 1960s that burning fossil fuels was destabilizing Earth’s climate. By the time I was teaching students about this a dozen years later, starting in 1980 in “Nature and Society: Energy,” a natural sciences class for non-science majors at the University of Colorado, Boulder, there wasn’t much doubt about it in the scientific community, and arguments were being made for dramatic changes in our energy supply to prevent serious and unpredictable consequences to the biosphere and human societies. Dale Jamieson was in the CU Boulder Philosophy Department then, honing his understanding of the philosophy and ethics of climate change through his work with people like Stephen Schneider and Michael Glantz from the National Center for Atmospheric Research. We knew then what we needed to do to prevent climate change from becoming the major problem that is has now become. But we did nothing. In his book, Jamieson says: “Our failure to prevent or even to respond significantly to climate change reflects the impoverishment of our systems of practical reason, the paralysis of our politics, and the limits of our cognitive and affective capacities.”

I’d heard more or less the same ideas before from Paul Ehrlich, a Stanford University ecologist, in my freshman “Introduction to Human Ecology” class. Ehrlich told us then that from the point of view of ecological science, we knew all we needed to know to take action; what was lacking was the political will to do so. In his book, Jamieson summarizes the sorry history of the U.S. political response to the scientific evidence about the threat of anthropogenic climate change. He shows how the all the efforts to stop climate change failed because of the American political process, which he characterizes as “… do as little as possible on climate change, rationalized by casting doubt on the science and exaggerating the costs of action. The division between the United States and Europe on the urgency of taking strong action on climate change, with binding commitments, continues to this day.”

And, Jamieson notes, “… climate change can be seen as presenting us with the largest collective action problem that humanity has ever faced, one that has both intra- and inter-generational dimensions. Evolution did not design us to deal with such problems, and we have not designed political institutions that are conducive to solving them.”

The scale of the political challenge of halting and reversing the use of fossil fuels to slow or halt climate change requires collective action, which we humans really don’t have any personal or political inclination, much less process or mechanism, to accomplish. Unfortunately, the human species flunks “collective action.” We are, because of our evolutionary history, a species torn between individual self-interest and collective action at the tribe-level. But global collective action, transcending both individuals and tribes? We simply don’t have the mental, psychological, or emotional capacity for that, apparently. We never needed it before, and evolution therefore never inserted it into our innate repertoire. Bottom line: we’re screwed. We might as well accept climate change, because it is too late to do anything about it, and even if it weren’t too late, we wouldn’t be able to do anything anyway. Neither current economics nor ethics are capable of resolving this problem.

Reason in a Dark Time is dense with citations and footnotes, and requires active, mind-engaged reading, but it illuminates the philosophical and ethical challenges we now face with wisdom, and a deep tenderness for our morally and politically handicapped species. I recommend it highly.

A few more ideas from the book:

- “I have argued that climate change presents us with problems of utmost complexity. Considerations ranging from our biological nature to facts about our political institutions all bear on explanations of why we have failed to act.”

- “… the origins of our commonsense morality are in low-population, low-density societies, with seemingly unlimited access to many natural resources, so it would not be surprising if there were questions relating to anthropogenic climate change about which our everyday morality is flummoxed, silent, or incorrect.”

- “What is important for our purposes is that this story does not have a happy ending. Climate change is not an isolated phenomenon but is occurring in concert with other rapid environmental, technological, and social changes. … The challenge is not (only) to reduce or stabilize the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide but to live meaningfully in relationship with the dynamic systems that govern a changing planet. This is a new challenge because humanity is young and now constitutes an important planetary force in a way that is unprecedented. In recognition of the increasing human domination of the planet, some scientists propose that we have entered a new geological era, the Anthropocene. Climate change may be the first challenge of the Anthropocene, but it will not be the last.”

But, like me, Jamieson is able to squeeze a last drop of hope out of what would appear to be a hopeless situation: “Despite the unprecedented nature of the challenge, human life will have meaning as long as there are people to take up the challenge. It matters what we do and how we live.” Thanks Dale. I hope so, at least.

——-

When President Obama was looking for a backdrop to talk about climate change, he ended up at the Exit Glacier in Kenai Fjords National Park. As I said earlier, Exit is the only one of the park’s 40 glaciers that can be viewed from land. All of the others plunge from the Harding Icefield into fjords reaching up into the Kenai Mountains from Resurrection Bay and the Gulf of Alaska, and must be viewed from the water. That usually means a trip with one of the marine tour companies specializing in this nature tourism market.

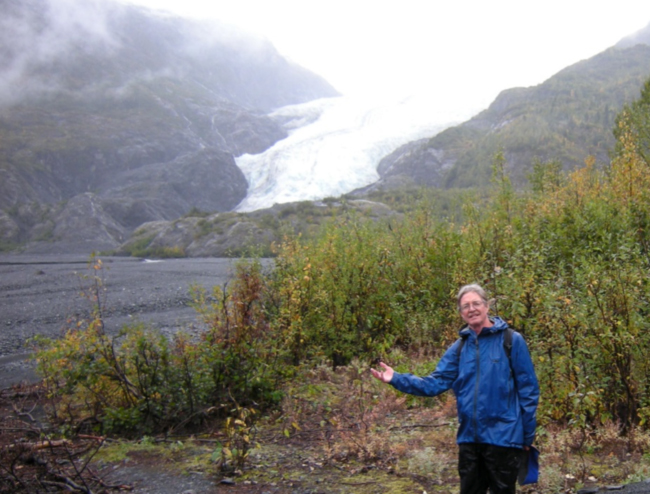

On Tuesday, September 1st, Obama hiked up to the terminus of the Exit Glacier on a glorious sunny morning. I followed in his footsteps on Thursday, September 10th, a miserable day – light rain at about 40 degrees F. was perfect for inducing hypothermia without appropriate clothing. Fortunately I was prepared: layers underneath, rain coat and rain pants on the outside.

We walked the same trail Obama had walked, and Jonathan, who had been in the official Kenai Fjords National Park group that accompanied the President, recounted his exact steps.

We stopped at the same spot where Obama gave a quick climate change “elevator speech” to the media flock following him: “So you guys have been seeing these signs as we’ve walked that mark where the glacier used to be — 1917, 1951. This glacier has lost about a mile and a half over the last couple hundred years. But the pace of the reductions of the glacier are accelerating rapidly each and every year. And this is as good of a signpost of what we’re dealing with when it comes to climate change as just about anything. This is one of the most studied glaciers because it’s so easily accessible. But what it indicates, because of the changing patterns of winters with less snow, longer, hotter summers, is how rapidly the glacier is receding. And it sends a message about the urgency that we’re going to need to have when it comes to dealing with this, because, obviously, when the glaciers erode, that’s also a sign of the amount of water that’s being introduced into the oceans — rising sea levels. And the warming, generally is having an impact on the flora and fauna of this national park. It is spectacular, though. And we want to make sure that our grandkids can see this.”

——-

In someone else’s blog in the next century they will describe how a now-gone finger of ice called the Exit Glacier once reached from the Harding Icefield toward the top of Resurrection Bay near Seward, Alaska. The world will be very different. Alaska will be very different. I’m glad to have seen it now. Obama said: “It is spectacular, though. And we want to make sure that our grandkids can see this…” Sorry Barack, our grandkids won’t see it. They will see something very different. They will see something even more different than the difference between what my dad saw and my children see. They will see the legacy of our failure to take appropriate political action, at root a legacy of our evolutionary history, our tribalism, our inability to make the personal political, our inability to develop a global environmental ethic. My time travels in Alaska showed me that already.

We can’t not live on a human-dominated planet. It is too late. We can never return to the planet our species evolved on. Our only home planet is already, irreversibly, dominated and altered by our species. The only question is, how do we live on it, starting now?

——-

Belugas were known to early Arctic whalers as “sea canaries” because their birdlike vocalizations could be heard even through the hull of a ship. Maybe my initial meeting with them, or their initial welcoming of me, was to make me aware, eventually, that they are the “sea canary in the climate change coal mine.” According to the IUCN Species Survival Commission, the international organization that monitors endangered species worldwide, future climate change is likely to affect belugas both directly through ecological interactions and indirectly through its effects on human activity. As sea ice in the Arctic declines and the Arctic Ocean becomes more navigable, human impacts on areas that were formerly refuges for belugas and other marine mammals will increase. Ironically, coal is still the main fossil-fuel culprit in melting the icy Arctic iceberg world that keeps them safe, and that they have evolved to exploit.

I looked, and I hoped, to see the belugas again as I drove toward Anchorage on the last day of my trip to Alaska. But I didn’t see them. They were gone, an ephemeral memory of the past, swimming somewhere into an unknown future.

For related stories see:

Sources and related links:

- Beluga whale in St. Lawrence Estuary, Canada

- Cook Inlet population of beluga whales listed under Endangered Species Act in 2008

- Kenai Fjords National Park

- Obama administration approves Arctic drilling ahead of president’s visit to Alaska

- Reason in a Dark Time. 2014. Dale Jamieson. Oxford University Press

- Stephen Schneider

- Obama’s photo at the Exit Glacier, 1 September 2015

- Remarks by the President at Exit Glacier, Kenai Fjords National Park, AK

- Obama visits receding glacier in Alaska to highlight climate change

- Obama hikes rapidly retreating Alaska glacier to raise awareness about climate change

- Beluga vocalizations

- IUCN Red List report on beluga whales and climate change