September 2013. A few months ago, preparing for an assessment of climate change adaptation and biodiversity conservation in Honduras, I was googling my way through the landscape of information that these days appears in response to any search of key words. When I tried various combinations of “Honduras,” hydrology,” “protected areas,” and “biodiversity,” the name Luis Caballero kept coming up in the first page of hits. This morning Luis and I were driving up out of Tegucigalpa on the road to Zamorano University, where he is a professor. In these few months Luis had come to be a key member of our assessment team, and he was taking me to see some of the watersheds that he has been studying for more than a decade here in the highlands of central Honduras.

It was a Sunday morning, and we had expansive views of the landscape as the road wound through the mountains. At one point the green farms of Zamorano spread across the sunny valley below, but the clouds still pressed down on the peaks of La Tigra, and Uyuca. These mountains are both protected areas, La Tigra as a national park, and Uyuca as a biological reserve. We passed through the park-like campus and teaching farms of Zamorano, and then started up toward Güinope (pronounced “gwee-no-pe”), sitting on a highland plateau above this valley. Zamorano and Güinope are in the Honduran department called “El Paraíso” – paradise.

Halfway up we entered a forest of Pinus oocarpa. This pine, called ocote in Spanish, is the national tree of Honduras. Ocote pine is found from western Mexico to Nicaragua, in mountainous areas above about 3,000 feet in elevation. The tall pines were branchless for ten or fifteen meters before branches started and spread to rounded crowns. Grasses, palmetto, giant maguey, and shrubs formed the understory; this was a pine savanna that had the familiar look of the woods of ponderosa pine in northern New Mexico where I grew up. Pine forests with this structure always suggest that fire plays a leading role in the ecological theater and evolutionary play. Pinus oocarpa is adapted to fire, even to the extent of having semi-serotinous cones – the botanical name for cones that stay closed, at least partially, until a wildfire heats and dries them, causing them to open fully and release a pulse of seeds that take advantage of the fire-prepared ground for germination.

Up on the flats we passed through farms and small settlements along the road. At one place some men were packing piles of roma tomatoes into old banana boxes, while a line of men and young boys carried buckets of the fruit from a field below, irrigated with water carried in a plastic pipe from a little drainage in the forest above. Most of these tomatoes are trucked to El Salvador, six hours away, where the demand, and price, are higher. One of the men said “hello” in English, and explained, in English, that his mother and sister live in Miami, where he visits three or four times a year. “I love the States!” he said.

We stopped to photograph a small stream coming from the watershed, and a twin-cab Toyota Hilux pickup passed going the other way, with the logo of the German Development Agency, GIZ, on the door. Luis started talking to the driver, Fredy Rodriguez, who was working for a GIZ project in the area. He was also a local small-scale coffee farmer. When Fredy learned I lived near Washington, D.C., he said he had a brother and other relatives there, in Gaithersburg, Maryland. They are trying to market his coffee in the Washington area. He invited us to his house in the town of Güinope to have a cup of coffee, and we stopped by later, after visiting some watersheds. This coffee from paradise was smooth and mild; even with no sugar it had an almost-sweet taste, balancing the bitterness.

Luis has been studying two neighboring microcuencas – micro-watersheds – above the town since 2003. He intalled V-notch wiers to measure the flow in the two small streams. Pressure transducers inside a concrete housing beside the wiers collected data on the water pressure, and hence the depth, of the stream. Stream flow can be calculated from that information. Besides measuring flow, Luis and his students have been sampling the water for sediments, minerals, nutrients, and organic matter. Rain gauges in the watersheds measure precipitation. The pair of watersheds differ in their proportion of forest and farms. The data from these instrumented watersheds can be used to show how land use affects hydrology. The goal of this research is to better understand the relationship between rainfall and and both surface and groundwater flows, and the important ecological effects on the water cycle occurring in forests and on farms.

The pond above the first wier was filled to the bottom of the V-notch with sand and rocks, some the size of small watermelons. “This never happened before, in ten years!” Luis said. “It must have been quite a storm!” Local roads above Güinope recorded the damage too. We needed four-wheel-drive in many places.

The small traditional farms in the lower part of these watersheds somewhat mimic the natural forest here – perennial tree crops dominate. Coffee bushes grow in the shade of orange and lemon trees and towering plantains, their roots binding the soil and their leafy canopy protecting it from the impact of raindrops. Much less soil is lost from forest farms like these than from fields of annual crops of maize and beans, or vegetable crops like tomatoes, peppers, onions, and carrots.

In the afternoon we headed down, again passed through the Zamorano campus, and turned toward Valle de Angeles, a charming tourist town that sits in the deep ocote pine woods on the eastern flank of La Tigra mountain. We were going to see the watersheds that Luis studied for his Ph.D. thesis at Cornell University. This was the research that had popped up on Google those months ago, and I was excited to have the chance to see the place on the ground.

La Tigra protects a significant area of tropical cloud forest, bosque nublado, a very special type of ecosystem with unique biodiversity, and often rich in endemic species. Epiphytes – plants that physically grow on other plants – are especially common in cloud forests, because they can harvest enough water condensed from the fog and clouds streaming through the forest that they don’t need to grow on the ground and use soil moisture. Bromeliads are a common plant family here, and orchids. Beside harvesting fog water, these cloud-forest epiphytes create specialized niches for insects and amphibians, multiplying species diversity.

For his thesis research Luis compared four micro-watersheds coming from La Tigra, one covered mainly in cloud forest, and the others with lower-elevation pine forests and some agriculture. The main findings are described in an article titled “Evaluating the bio-hydrological impact of a cloud forest in Central America using a semi-distributed water balance model,” published this year in the Journal of Hydrology and Hydromechanics. The study showed that the cloud forest produced greater groundwater recharge than the non-cloud forest watersheds. This resulted in watershed discharge on a per area basis four times greater from the cloud forest than the other watersheds. Luis and his co-authors conclude that “These results highlight the importance of biological factors (cloud forests in this case) for sustained provision of clean, potable water, and the need to protect the cloud forest areas from destruction, particularly in the populated areas of Central America.”

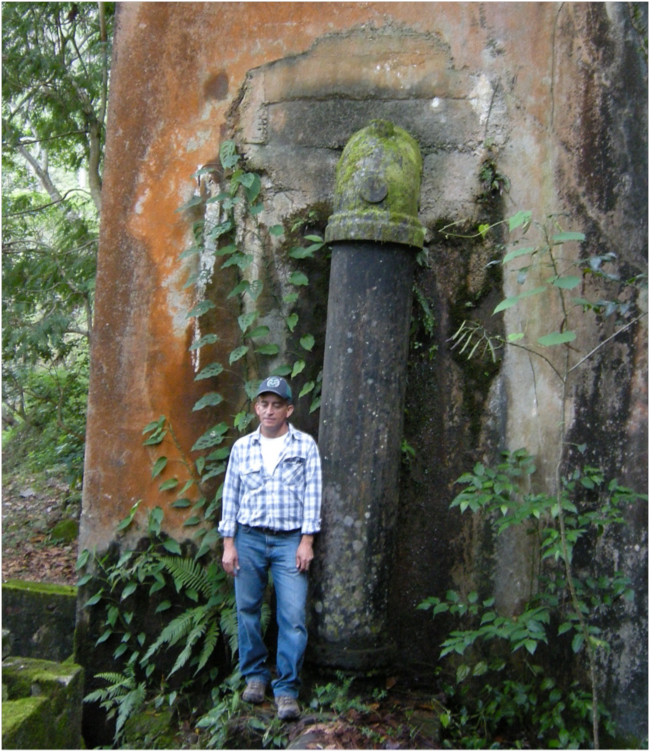

Water diversion structure capturing all the water in this stream coming from La Tigra for Tegucigalpa drinking water

To reach the stream-guaging wiers Luis built in 2008 for his study, we parked at a locked gate a kilometer or so into the forest above the main road between Tegucigalpa and Valle de Angeles. We walked briskly up the narrow valley. Big Pinus oocarpa covered the slopes above us. In about ten minutes we came to a concrete structure where a large pipe led into the steep side of the valley. Water, taken from a catchment structure just upstream, passed through this pipe in a tunnel that led downhill under the mountain to Tegucigalpa on the other side. Another hundred meters up the valley the concrete catchment structure swallowed the entire flow of the stream and put it into the big pipe. Above the dam was a crystal-clear splashing stream; below it, a dry, rocky streambed.

People in the capital don’t pay anything toward the protection of the La Tigra cloud forest that supplies this water – some 25% or more of the drinking water for the city. Some people, including the non-governmental organization Fundación Amigos de La Tigra (Amitigra), who co-manage La Tigra National Park, think that should change, and that domestic water users in Tegucigalpa should pay some of the costs of protecting and managing the park. In the Honduran system of protected areas, NGOs, or sometimes other kinds of organizations, are given rights to co-manage a protected area in collaboration with the responsible government agency, the Instituto Conservación Forestal, ICF. But funds needed for proper protection and management are usually lacking, and management often suffers. Amitigra argues that a “payment for ecosystem services” mechanism, where water users in Tegucigalpa are charged a small fee that is then used to fund proper park management, would ultimately help sustain the cloud forest ecosystem that contributes to the water supply.

See More Photos

Related Links

- Caballero, et al., 2013. Evaluating the bio-hydrological impact of a cloud forest in Central America using a semi-distributed water balance model

- Fundación Amitigra

- Reserva Biológica “El Uyuca”

October 23, 2013 12:59 am

Bruce, me alegro que hayas tenido la oportunidad de visitar las micro-cuencas de investigación del Dr. Caballero; es un gran aporte científico no solamente para la formación académica de la Universidad El Zamorano, sino, que también para los formuladores de propuestas de proyectos en manejo de cuencas y recursos naturales en Honduras y centro américa. Esto lo hemos podido corroborar en los sondeos que hemos hecho con diferentes actores en la Región Sur de Honduras, en relación al estudio sobre Resiliencia al cambio climático, manifestándonos el interés de considerar en futuros proyectos estudios de este tipo que nos permitan con base científica identificas practicas y tecnologías que pudieran contrarrestar el impacto del cambio climático. Lastima que en nuestro querido país Honduras muy poco se invierte en este campo y no valoramos los aportes que científicos como el Dr. caballero pudieran proporcionar a los tomadores de decisiones; a tal grado que para seguir contribuyendo desde el campo científico a veces tienen que buscar otros horizontes. Muy interesante resumen Bruce y felicito al Dr. Caballero por esta iniciativa.

October 24, 2013 3:25 pm

Muchas gracias, Olman, por sus comentarios!

October 23, 2013 9:09 am

Excelente artículo Bruce¡ Te felicito¡

October 24, 2013 3:27 pm

Gracias, Carlos! I’m glad if you enjoyed this. It should have some relevance for similar issues of the relationship between conserving natural ecosystems and hydrological functioning and ecosystem services in the Dominican Republic, no?