November 2015. A serendipitous trip to the Outer Banks of North Carolina in early November gave me a personal, human scale for understanding some ecological facts about climate, climate change, and coastal plant communities. I ran the Outer Banks Marathon on Sunday, 26.2 miles. On Tuesday I went to Cape Hatteras and walked in Buxton Woods, the largest area of maritime forest on the Outer Banks. This relict forest on Hatteras Island is now just about a marathon distance from the mainland across Pamlico Sound. About a marathon distance to the east is the Gulf Stream, which circulates tropical water closer to the East Coast here than at any other point. It turns out that this spatial scale has corresponding temporal dimensions. Here at Cape Hatteras I was about a marathon distance west from the post-Ice Age shoreline of this coast about 5,000 years ago, out where the Gulf Stream runs now, and only a few marathons east of the pre-Ice Age shoreline of 125,000 years ago. I was at a focal point of dramatic ecological and climatic changes, all only a marathon or so away. OK, it’s a bit complicated. I’ll try to explain.

——-

Buxton Woods is the largest remaining tract of maritime forest on the Outer Banks. We parked not far from the famous Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. The whole area is part of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, a multiple-use mosaic of public and private lands designated by Congress in 1937. The first national seashore park, Cape Hatteras National Seashore is under the overall management of the National Park Service, and was established to conserve the diverse values of this complex land-and-seascape, from Bodie Island to Okracoke Island.

On November 10th the air was steamy, tropical, with a temperature in the high 70s, and on the Buxton Woods Nature Trail the mosquitoes were fierce. The Nature Conservancy’s online information on the Buxton Woods Coastal Reserve says: “The forest’s great natural diversity can be attributed to the sheltering effects of the ancient dunes and the moderating temperatures on the cape. Over a dozen rare plant and animal species occur here, some at the northern end of their range.”

One prominent example of a species at the northern end of its range is the dwarf palmetto, Sabal minor. Palmettos are a New World group of the palm family, distinguished by their pleated, fan-shaped leaves. Most palms are found in the tropics, and American palms reach their northern natural limit here on the Outer Banks, represented by the dwarf palmetto.

But just above the palmettos, scurrying along branches of live oaks, was the eastern grey squirrel, Sciurus carolinensis, a tree squirrel found throughout forests of eastern North America. Buxton Woods is an ecosystem where the tides of climate change over hundreds of millennia have thrown together the bits and pieces of ecosystems from different directions. This is an ecologically-jumbled, mixed-up forest, it was clear. How did all the pieces of the Buxton Woods puzzle get here?

——-

From here on Cape Hatteras, it is about a marathon to the Gulf Stream. If I could run on water and started here on Sunday morning instead of in Kitty Hawk, I could run to the Gulf Stream’s tropical waters in less than five hours, and dance on the waves with the marlin, swordfish, tuna, and other fast-running fish.

The Gulf Stream is a fast and relatively narrow ocean current, about 40-50 miles wide, that carries warm water from the tropical Atlantic north along the east coast of North America, and across the North Atlantic toward northern Europe. Off of Cape Hatteras, it is often only around a marathon distance offshore, usually nowhere closer to the U.S. coastline than here. At the website for the National Weather Service’s Ocean Prediction Center, you can watch a model forecast of the Gulf Stream, and see how close it is to Cape Hatteras on any given day. Because it is so close, Hatteras Harbor Marina just south of Buxton is the premier launching point for charter fishing boats taking clients to fish for blue marlin, sailfish, swordfish, tuna, dorado, and wahoo in the Gulf Stream.

Benjamin Franklin, interested in the speed of ships sailing east or west across the North Atlantic, investigated the “Gulf Stream” current. Working with experienced American ship captains, including a distant cousin Timothy Folger, a Nantucket whaling captain, he learned enough to chart the current. It was Franklin who gave it the name by which it is still known today.

The palms on Cape Hatteras are here because of the Gulf Stream. In fact, a sign along the trail in Buxton Woods talks about the moderating influence of being so close to the Gulf Stream, and surrounded by water: freezing temperatures are experienced here on Cape Hatteras only 13 days a year, on average – five fewer than in Tallahassee, Florida, about 800 miles southwest. Ocean and land and climate are completely connected here.

Many climate models predict that global warming will alter the circulation of ocean currents in unpredictable ways, including that of the Gulf Stream. Better do your marlin fishing from Cape Hatteras soon, if you’ve ever wanted to, and prepare to bid goodbye to the palms of Buxton Woods.

——-

Buxton Woods has been under threat from human activities for more than 100 years. The Cape Hatteras maritime forests attracted the attention of the “forest crusaders” of the late 1800s, including Gifford Pinchot, who later, in 1905, was appointed the first head of the newly-established U.S. Forest Service by President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1892, George Vanderbilt hired Pinchot, fresh from his forestry studies in Europe, to manage his private forest reserve at the Biltmore Estate near Ashville, North Carolina. Pinchot stayed there until 1895, and in 1897, as a private forestry consultant, surveyed North Carolina forests for the North Carolina Geological Survey. His report was the first to characterize the maritime forests of the Outer Banks, and he reported that timber cutting had mobilized sand dunes, which were engulfing communities and the forests themselves. “Some such areas were originally forest-covered,” he wrote, “but once cleared… the constant movement of the sand before the winds, which have piled it into shifting dunes, has prevented a general growth of any kind from securing a foothold.” Pinchot and other forest conservationists of the era took this as further evidence that humans had disturbed the natural balance of nature in dangerous ways, requiring correction through forest conservation and sustainable management.

Pinchot was not aware of it, but recent research has demonstrated that the maritime forest of Buxton Woods provides a critical ecosystem service to the local human community of Buxton by trapping rain in its freshwater ponds. That freshwater lens pushes down on the underground saltwater that would otherwise push to the surface here and destroy the freshwater aquifer that is tapped by the town for its domestic water supply.

Modern research about the dynamic nature of the Atlantic Coast, its barrier islands, and their maritime forests, tapping into deeper geological knowledge than was available in Pinchot’s time, calls into question whether any human action could oppose the dynamic forces of a changing planet on the Outer Banks. Although Pinchot and other forest conservationists were probably correct in blaming human overexploitation of the maritime forest on Cape Hatteras for an increase in dune movement, the view from a longer time-perspective situates that human threat in a larger context. A 2003 study by Jim Senter, Live Dunes and Ghost Forests: Stability and Change in the History of North Carolina’s Maritime Forests, concludes that “while many aspects of the history of North Carolina’s maritime forests need further investigation, the preponderance of the evidence presented here supports the conclusion that human activity was not the primary cause of the live dunes in the region. At the end of the Little Ice Age, an increase in the rate of sea level rise and in storm frequency increased the number of overwash events, and the vegetation responded… From this perspective, rather than a stable forest primeval, the vegetation of barrier islands is as dynamic a part of the island landscape as its human populations and geological structures.”

——-

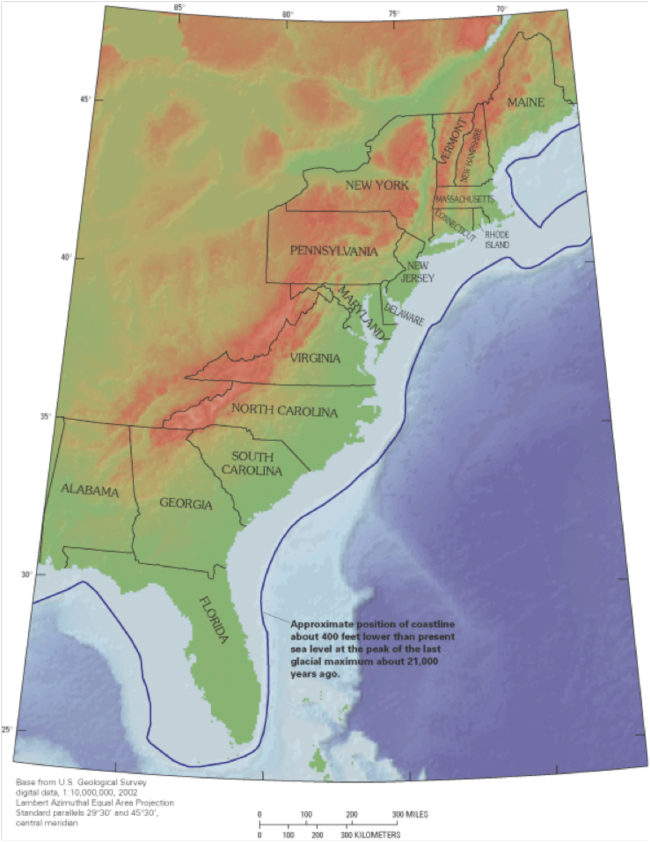

If I could run on water and started here on Sunday morning instead of in Kitty Hawk, I could run a marathon east to the shoreline of around 5,000 years ago, when sea level was much lower because so much water was still locked up in glaciers and icecaps. And by 5,000 years ago, sea levels were already rising. A 2003 publication by the U.S. Geological Survey states that “the global sea level was a maximum of about 400 feet (125 meters) below the present level at the peak of the last glacial maximum about 21,000 years ago.”

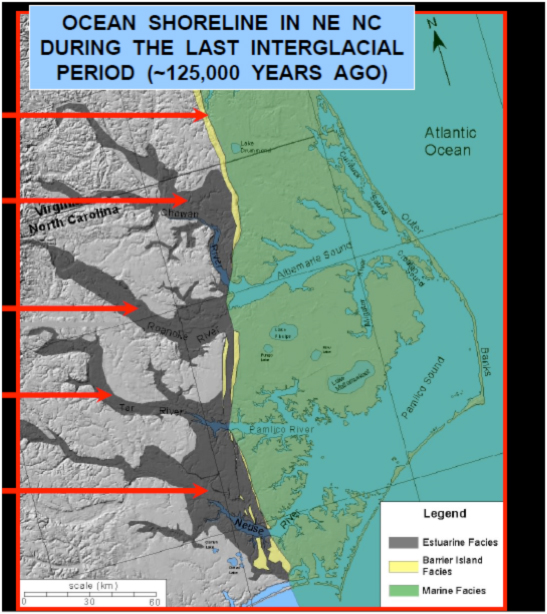

About three marathons to the west of the current location of the Outer Banks, ancient sand dunes, now forest-covered, mark the position of the North Carolina shoreline during the last interglacial maximum about 125,000 years ago, when sea level was dramatically higher, and what is now Hatteras Island was under water.

It’s enough to dramatically complicate, if not completely confuse, my perspective on “climate change” and the discussions about its dire effects taking place right now at the U.N. Climate Change Conference in Paris. Our species has such a short time horizon. Science can extend it, stretching our imaginations, and expanding our view of the human-nature relationship.

I thought of my recent trip to Alaska’s fjords and glaciers. Here at Cape Hatteras, I was on the opposite side of the continent, perhaps seeing the counterpoint to the relict, isolated population of beluga whales I’d seen in Turnagain Arm south of Anchorage, in this isolated maritime forest, now thirty miles off the North Carolina mainland because of rising sea levels caused by melting ice.

——-

The dwarf palmetto is one of a species rich genus of New World palms, with at least 15 species found from northern South America and through the Caribbean to Florida, the U.S. Gulf Coast, and as far north as the Outer Banks. The diversity of palmettos is probably the result of speciation driven by the isolation and reconnection of their ancestral populations as the climate pulsed with the ice ages. As sea level retreated and advanced over the past hundreds of thousands of years, isolating patches of forest on barrier island blocks as the ice melted and sea levels rose, and then reuniting them with contiguous mainland forest again as ice advanced and sea levels fell, the conditions for speciation were created again and again.

Another group of species that could be the result of similar evolutionary dynamics are the American hollies of the genus Ilex. In the U.S., hollies are represented by about 14 species, found mainly in on the coastal plain of the southeastern states. The shifting archipelagoes of isolated forest patches created by climate change and sea level rise and fall also may have created the conditions for the speciation of hollies in the southeastern U.S. In Buxton Woods, there were several species, including Ilex opaca, American holly. Their white trunks were a palette of lichens – red, orange, gold, and brown patches covered the bark. These lichen maps seemed to me an apt image for the islands of isolation and speciation that climate change may have created here.

So, the palmettos and hollies, the live oaks and grey squirrels – in other words, the biodiversity of Buxton Woods and other Atlantic maritime forests – may be the result of the dynamic climate, and climate change, that is now being seen as a threat to biodiversity. It depends on your time horizon. Our human time horizon is very short.

The “ultimate goal” of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, UNFCCC, is to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations “at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic (human induced) interference with the climate system.” Out of their climate-model “hat,” scientists advising the UNFCCC decided that if global warming could be limited to two degrees Celsius above the recent historical background temperature of the planet, we would avoid “dangerous” climate change. But what is “dangerous?” Were sea level changes caused by natural, non-anthropogenic climate changes during the lifetime of our species “dangerous?” Apparently not, to humans; and they may have been a driver for the evolution of new non-human species.

Of course we have “anthropogenic interference with the climate system.” And that forcing of the climate system caused by our fossil fuel addiction may be much faster than previous natural climate evolution – although some evidence suggests that even natural climate changes could be dramatic and fast. But what is dangerous, now, is that our unwise and selfish species has filled up the planet to the brink, driving other species to extinction, and dominating most of Earth’s ecosystems with our agriculture, fishing, and other activities. We have pressed against and exceeded the carrying capacity of the planet for our own species, and created a new geological epoch of human dominance of the Earth system. If it weren’t for that – that is, if we weren’t already courting our own extinction for a host of other reasons – all the changes that climate could throw at us would just be another surmountable challenge, like our species has surmounted innumerable times in our past evolution.

The ecophilosophical question seems to be: Isn’t it a bit strange, even anthropocentric, to call what we have created by our own unwise choices “dangerous climate change?” What was and remains dangerous are all of those same unwise choices we have made about the human-nature relationship, not really a changing climate.

OK, it’s all a bit complicated, both ecologically and philosophically. Have I explained it all, as I said I would try to do in my opening paragraph? I hope so, and I doubt it.

——-

Later on that very same night, back in an oceanfront bedroom in Nag’s Head, windows thrown open and a gentle surfsound swishing in, I had a strange dream. At the end of a marathon run, I was surrounded by a crowd of talking palmettos. “Don’t worry,” they said, “we’ll be fine, we’re adaptable. We’ve been moving in and out, up and down, and all around for hundreds of millennia. Climate change? We’ve seen it all before, we can handle it! If you want to worry, worry about your own species. You are the ones who haven’t yet learned to relax and adapt to what our planet blesses us with. You are the species at risk because of your own actions. You are the only species at risk of extinction by your own choices. Don’t worry about us, we’ll be fine!”

For related stories see:

- Beaches and Dunes, Kiunga Marine National Reserve

- Pondering the Ponds of Nags Head Woods

- Outer Banks Encounters

- Not Nature Apart Either: A Case Study of Point Reyes National Seashore and the Drakes Bay Oyster Company

- Breaking the Curse of Voodoo Economics and Designing an Ecological Economy

- Lunch at Grey Towers

- Time Travels in Alaska

- Travels in Alaska: Seeking the Sublime Among Glaciers and Fjords

Sources and related links:

- Outer Banks Marathon

- Cape Hatteras National Seashore

- Buxton Woods Coastal Reserve. The Nature Conservancy.

- The Interpreter’s Guide to Seashore Life on Hatteras Island. National Park Service.

- Bellis, Vincent J. 1995. Ecology of the Maritime Forests of the Southern Atlantic Coast: A Community Profile. U.S. Department of the Interior.

- Gulf Stream

- Gulf Stream Forecast Model, National Weather Service, Ocean Prediction Center

- Lee, Gabriel F. 2008. Constructing the Outer Banks: Land Use, Management, and Meaning in the Creation of an American Place.

- Senter, Jim. 2003. Live Dunes and Ghost Forests: Stability and Change in the History of North Carolina’s Maritime Forests.

- S. Geological Survey. 2003. Ground Water in Freshwater-Saltwater Environments of the Atlantic Coast. Paul M. Barlow.

- Stanley R. Riggs, Dorothea V. Ames, Stephen J. Culver and David J. Mallinson. 2011. The Battle for North Carolina’s Coast: Evolutionary History, Present Crisis, and Vision for the Future. U. of North Carolina Press.

- Stanley R. Riggs. Climate Change, Sea-Level Rise, and Coastal System Evolution: Overview of the Mid-Atlantic System. NOAA Presentation.

- Sara Peach. 2014. Rising Seas: Will the Outer Banks Survive? National Geographic.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Essential Background.

- “The magic number: Holding warming under two degrees Celsius is the goal. But is it still attainable?” 29 November 2015. Chris Mooney. The Washington Post.

December 9, 2015 4:28 pm

Very interesting rumination, Bruce. Thank you for it.

So in my overly quick read, am I to conclude that climate change per se is less of an issue (i.e. is not “the” issue) than simply rotten human interaction with the biosphere overall, period?