From the terrace in front of the mansion, with its stone towers and steep roofs of shiny grey local slate, the lawn sloped steeply down toward the town of Milford, Pennsylvania, and gave a long view east over the Delaware River to forested hills, a pale spring green now on a sunny mid-May morning.

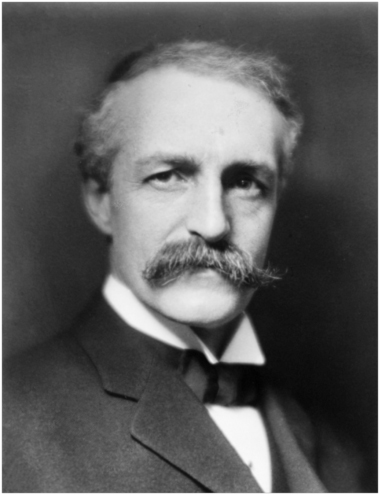

I was here because I wanted to have lunch and a conversation with Gifford Pinchot, a man often called “America’s first forester.” Pinchot was appointed by Teddy Roosevelt to lead the U.S. Forest Service, newly-established in the Department of Agriculture, in 1905. He died in 1946, so I was a bit late to talk directly with him. This was a séance of sorts: I wanted to roam the halls and grounds of Grey Towers, the house where Pinchot lived and worked, hoping to have a conversation with his spirit, even if only in my imagination.

Grey Towers is now a National Historic Site, managed by the U.S. Forest Service; it was donated to the U.S. Government by the Pinchot family in 1963. The house was built between 1884 and 1886 by James Pinchot, Gifford’s father, son of a French Huguenot family that settled in Milford a generation earlier, who made a fortune in the wallpaper business in New York City. On his 21st birthday, celebrated here on August 11th, 1886, Gifford’s parents gave him a copy of George Perkins Marsh’s 1864 book Man and Nature – the birthday book is on display in the mansion. Man and Nature was an early exploration of ecological ideas and a plea for conservation. Marsh wrote that “the operation of causes set in action by man has brought the face of the earth to a desolation almost as complete as that of the moon.” He argued that human welfare required the management of nature to maintain its benefits to society. James Pinchot and his son agreed strongly with this perspective.

James Pinchot had witnessed the environmental damage that forest-product industries such as his wallpaper business had done, and he used his substantial means to try to make amends. He promised to restore the forests and implement responsible forest stewardship on the many deforested acres surrounding Grey Towers. He persuaded his talented son Gifford to go to France to study the latest European forest management methods, and then transplant them to the United States. In 1900, he endowed the Yale School of Forestry, the first graduate forestry program in the country, and from 1901 to 1926, the Grey Towers estate grounds were the site of the school’s summer field program. He established the Milford Experimental Forest nearby as a site for forestry research.

_____________________

Part of my interest in Pinchot stems from my own family history. A great-great grandfather on my mother’s side, Alexander Eisenbise, was born in in Lewistown, Pennsylvania, a once-prominent commercial center on the Juniata River in 1814. Beginning in the 1700s, Pennsylvania became the heart – or hearth – of American iron-smelting. There was iron ore in many places, and the forests of “Penn’s Woods” were an immense energy resource. Charcoal-fueled smelting furnaces harvested the local forests and turned ore into iron. Cast iron stoves were one product much in demand, and immigrant German stovemakers brought their foundry skills to Pennsylvania to create stoves that were both efficient and aesthetic. The informal genealogy handed down to me by my mother placed the Eisenbise family among these iron-smelting, stove-casting immigrants. “Eisen” is the German word for “iron,” and surnames in those days were often based originally on a trade. I’ve been trying to figure out the “bise” part of the name over the years; the closest I can come is the similarity of “bise” to “biss” – in German, to bite.

In any case, my iron-jawed Eisenbise ancestors settled for awhile in central Pennsylvania before my great-great grandfather Alexander moved west to Columbus, Ohio. There, one weekend on an Ohio riverboat, Alexander’s beautiful auburn-haired daughter, Laura, caught the eye of my Irish immigrant great-grandfather Patrick Sweeney, and the rest is history, as they say. Part of my history, at least. Maybe my dose of Eisenbise genes explain why every winter night finds me sitting by the woodstove in my livingroom, indulging my addiction to the ancient alchemy of wood, fire, and iron.

Twenty miles west of Lewistown, up toward State College, is Greenwood Furnace, now a Pennsylvania State Park and a National Historic District. This area produced some of the highest-quality charcoal-smelted iron in the U.S. for about seventy years. A company town of more than a hundred buildings surrounded the furnace, housing the woodcutters, charcoal makers, iron makers, and their families. The Greenwood Furnace went into blast – the term for a firing of the smelter – in 1834. Freedom Iron Works owned the furnace, a source of high-quality ore three miles away, and almost 40,000 acres of forest for making charcoal to smelt the ore. A charcoal furnace like Greenwood gobbled about an acre of forest a day to fuel its blasts. Teams of woodcutters worked full time making the fuel by clear-cutting the local forests with hand saws and horse teams. Let’s see… do the math: seventy years of ironmaking would require clearcutting more than 25,000 acres of forest. Looking at the forested hills around the Greenwood Furnace now, it is hard to imagine that when it shut down in 1904 there was hardly a tree in sight.

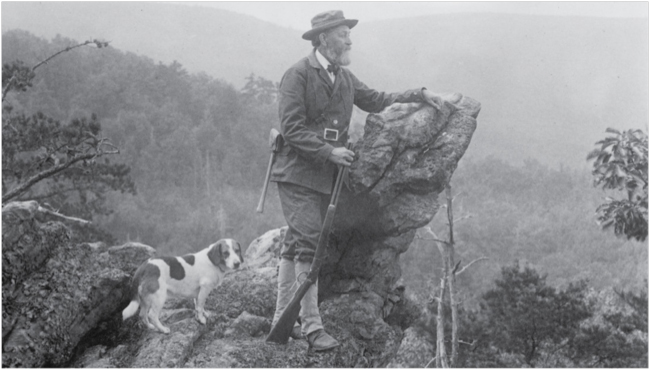

At some point, the wealthy furnace owners began to see a problem. They were burning the forests much faster than they could regrow; wood was a limiting factor to their economic bottom line. Some Pennsylvania politicians finally took notice, and in 1895 created a Division of Forestry within the state Department of Agriculture, appointing Dr. Joseph Rothrock as its head; he has been called the “Father of Forestry in Pennsylvania.” In 1903, when the Greenwood Furnace was about to close, Rothrock pushed the state to purchase 35,000 acres of deforested land nearby. This area, surrounding Greenwood Furnace State Park, is now the Rothrock State Forest. Like my ancestors the Eisenbises, the Rothrocks were also German immigrants to Pennsylvania. Like his contemporaries Gifford Pinchot and John Muir, Rothrock had his own adventures in the western U.S., serving as surgeon and botanist on the Wheeler Survey from 1873-1875. And in 1880, Rothrock studied botany at the University of Strasbourg, where he learned about European developments in forest management, ten years earlier than Pinchot’s studies at the French National Forest School in Nancy.

It was Pennsylvania’s rich coal deposits, and new technologies for smelting iron with coal instead of charcoal – not improved, scientific forest management – that finally saved Pennsylvania’s forests, however. The technological developments in smelting iron with coal were brought to the U.S. from England, which had turned to coal in desperation after cutting most of its own forests. The anthracite deposits along the Susquehanna River in northeastern Pennsylvania soon turned it into a hub of steelmaking, railroads, and industry, taking pressure off the forests as a source of industrial fuel, and enabling Rothrock and his successors to succeed in beginning to regrow Penn’s Woods.

Another part of my interest in Pinchot is due to my interest in another founding father of American conservation, John Muir. If you have read about Muir, you know about the last, losing battle of his long career to protect America’s wild places: the fight over a dam in the Hetch Hetchy Valley of Yosemite National Park. And you may have heard that on that issue, Gifford Pinchot sided with the dam’s proponents. Muir died of pneumonia, on Christmas Eve, 1914, a year after President Woodrow Wilson approved the Hetch Hetchy dam in December, 1913. Some Muir faithful would say that the Hetch Hetchy decision killed Muir in spirit, and some blame Pinchot for his role in that decision. My reading of the Muir-Pinchot relationship is more ambiguous and positive.

_____________________

After the tour of Grey Towers ended, I sat by the so-called “Finger Bowl,” a concrete pool of irregular shape, its bottom painted blue, on the side terrace under a wisteria arbor. The pool has a wide rim just at the height of a dining table. It had been the idea of Cornelia, Gifford’s sociable and progressive wife. Through the 1920s and 1930s, during her husband’s two terms as Governor of Pennsylvania and her own three attempts to run for Congress, Cornelia redesigned and modernized the Grey Towers home and grounds, trying to create a physical setting for social gatherings that would be a crucible for progressive ideas. In the early 1930s she worked closely with New York architect William Lawrence Bottomley to design the Finger Bowl as an informal, intimate social setting for discussing the important issues of the day. Politicians, businessmen, conservationists, and writers joined the Pinchot family around the rim of the pool, and ideas passed back and forth across the water during luncheons served on floating trays.

Finally I was alone with the place; I may have dozed a bit in the breeze under the wisteria shade…

Slowly the guests took their places around the pool. Gifford was the first to arrive, looking exactly like in his pictures, although dressed more casually than in many of them. John arrived next, and took a seat at the end of the pool. Alexander Eisenbise floated in and sat silently, his style of dress and the cut of his beard almost exactly the same as Muir’s. Finally Joseph Rothrock joined us, escorted to the poolside by Cornelia. I think it was Cornelia, never one to shy away from political debate and controversy, who invited this mix of guests to this luncheon séance. I had only hoped to have a quiet conversation with her husband, and I dreaded the possibility of an acrimonious debate here in this peaceful setting.

Lunch was served. Trays of food were placed on thick balsa-wood rafts or in floating wooden bowls that could be gently pushed back and forth across the water table. One tray held slices of beef and pieces of fried chicken. Another had a colorful array of vegetables: peas, carrots, asparagus, tomatoes, potatoes, lima beans. A bowl held bread and butter. After the meal coffee was served, and a bowl of fruit slid back and forth across the water with the talk and grand ideas.

“Tell me, Gifford,” John said, as he pushed a tray across the pool to him – I was afraid he would raise the grazing issue, one of their disagreements about public lands policy, and he did – “How could you support putting those hoofed locusts onto our public lands? I’ve told you about the devastation I’ve seen this sheepgrazing do in my own Sierra country. This isn’t something that can be maintained in our western lands without utterly degrading them. You know that as well as I do!”

Pinchot replied that his strategy was merely political expediency – to buy time with western legislators until a strong national agency to manage public lands and forests could be put in place. “You must know, John,” he said, “the first great fact about conservation is that it stands for development. There has been a fundamental misconception that conservation means nothing but the husbanding of resources for future generations.”

Although Muir is thought of by many people as a “preservationist” because of his work to protect national parks and stop the building of the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, he was in many ways a very pragmatic conservationist. In an article that argued for the creation of a system of national forest reserves titled “A Plan to Save the Forests,” published in Century Magazine in 1895, Muir had written: “It is impossible… to stop at preservation. The forests must be, and will be, not only preserved, but used. Forests, like perennial fountains, may be made to yield a sure harvest of timber, while at the same time all their far-reaching beneficent uses may be maintained unimpaired.” His progressive, pragmatic view was a balance between sustainable use and long-term protection.

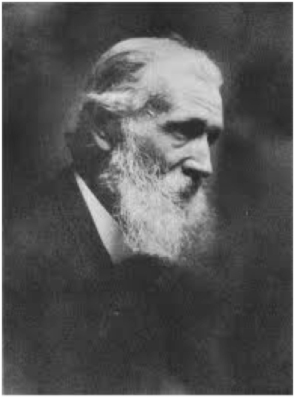

I knew that Muir first met Gifford at the New York home of his father James Pinchot in early June, 1893. Then 27 years old and fresh from his first professional job as consulting forester at the Biltmore Estate, George Vanderbilt’s Gilded-Age mansion in Asheville, North Carolina, Gifford was thrilled to meet Muir, 27 years his senior, who already had a reputation for defending America’s forest lands from the ravages of local exploiters. The two men met again in the West three years later, in 1896, on a survey of western forests under the auspices of an official National Forest Commission that was organized by the National Academy of Sciences and led by Harvard botanist Charles Sprague Sargent. At the time Pinchot wrote: “I met the Commission—Sargent, Brewer, Hague, and Abbot—at Belton, Montana, on July 16. To my great delight, John Muir was with them. In his late fifties, tall, thin, cordial, and a most fascinating talker, I took to him at once.” According to Donald Worster’s biography of Muir, the two men were the rebels of the expedition, chafing at the regimentation imposed by Sargent, and they developed a close friendship that summer. Toward the end of that grand western forest tour they camped together by a fire on the rim of the Grand Canyon, while the rest of the party slept indoors. Pinchot wrote about that experience in his autobiography, Breaking New Ground, and described Muir as “a storyteller in a million.”

“But remember Gifford,” John finally said, “your parent’s favorite environmental writer, George Perkins Marsh, warned us that ‘the equation of animal and vegetable life is too complicated a for human intelligence to solve, and we can never know how wide a circle of disturbance we produce in the harmonies of nature when we throw the smallest pebble in the ocean of organic life.’ If that is true, can you seriously propose that you can treat Nature as if she were your farm?”

After a short pause during which I feared the worst, Pinchot responded calmly (maybe it was Cornelia’s womanly influence on the gathering, I don’t know):

“My dear old friend,” he said, “I remember a night long ago, when we watched the stars stretching above the Grand Canyon together, and you quoted your friend Emerson about ‘hitching your wagon to a star.’ You said that for you, you felt that everything was connected – something about ‘when we try to pick out anything by itself, we find that it’s hitched to everything else in the universe.’ I agree with your philosophy… But what are we – we in leadership positions in government, or leaders of opinion in the popular press like you – to tell the people? If we don’t understand everything, and the demands of the people are so urgent, do we have the luxury to wait until we see how everything is connected before we cut a tree or catch a fish?”

“Marsh spoke strongly to me too,” interjected Rothrock, “and I must say we did not heed his warning soon enough. In fact, I’m not sure we have, still.”

My great-great-grandfather Eisenbise spoke out too: “Ach! When I was growing up in Lewistown, there were a lot of trees, but they were going fast. We could see what we were doing to the forests, and we could see that we were destroying the very foundation of our lives – but we didn’t stop. We couldn’t stop ourselves it seemed! In the end, we just moved on, abandoning the ruined forests that had been our home and hearth. Why couldn’t we understand, why couldn’t we stop it?” I was glad that he was not shy to add his views; I guessed by the similar twinkles in their eyes that he and Muir immediately saw each other as old friends.

“You may be encouraged to know, Alexander, that we have declared the area around the old Greenwood Furnace, just west of our mutual hometowns, a Pennsylvania State Forest,” said Rothrock. “It’s in bad shape now, of course, but we aim to restore that old forest.”

“Old forest! Restore it!” John exploded. “Och! You Eastern men have hardly seen real old forests, like ours out West! They were destroyed here even before I set foot on this continent! And then my own family set to work destroying those farther west, in Wisconsin, when we arrived from Scotland! But look, if you are going to restore natural forests, you have to have some samples of them, preserved in their original wild condition, so you know what you might aim for in your ‘restoring.’ Don’t we need some wild lands, preserved not as tree farms, but as examples of what Nature, not people, intended on this land?”

“Imagine,” Muir continued, “what could happen if we continue to allow these greedy lumbermen to take the most valuable species out of these woods, even if they don’t clearcut them for charcoal like our friends Alexander and Joseph have seen in the central part of your state? Like the chestnut! They are going fast, I have heard. And then – just imagine – what if, in their reduced numbers, suddenly a chestnut disease, a blight, were to appear? Imagine it, my friends! As Marsh warned, the workings of Nature are much too complicated for us to understand, and if we don’t understand them, how can we pretend to control and manage them like our forest farm?”

I felt goosebumps along my spine at these words coming from Muir. I almost felt he had tapped my mind, in a Spockian, Star-trekian Vulcan mind-meld, and somehow looked into the future through me. “Blight” – he had used that word! But how could he even imagine that an introduced disease, the chestnut blight, would wipe out the keystone tree of eastern forests, before it really happened? How could he imagine that now some people are using the genetic diversity of chestnuts that survived in tiny pockets of protected lands, wild lands – witness stands from the old forests – to try to regenerate and restore this keystone species to these eastern forests?

But again, unexpectedly, my great-great grandfather Alexander Eisenbise spoke up: “Ach, I agree with you John! My own daughter Laura Isabelle has just married one of the Irishmen driven from that country by the potato blight! How could they have imagined that their farms, which they thought they knew and controlled and managed so carefully, could be so suddenly devastated by a blight? Well, I’m blessed to have Patrick Sweeney join my family, but to me it says that we don’t really control Nature, even on our real farms – much less on your forest farms, Gifford.” I was a bit surprised that he would confront Gifford Pinchot so personally and directly, but secretly pleased that he felt comfortable enough with the famous man to do so.

And then Cornelia brought in her perspective: “My dear gentlemen, the conservation problem is not concerned only with the natural resources of the earth. Rightly understood, it includes also the relation of these resources and of their scarcity or abundance to the wretchedness or prosperity, the weakness or strength of peoples, their leaning towards war or towards peace, and their numbers and distribution over the earth.” My god, I thought: she’s bringing up poverty, inequality, governance, resource conflicts, demography – all of the factors that cause the unsustainable use of natural resources that conservationists are grappling with now. This woman is way ahead of her time!

So far the subject of Hetch Hetchy hadn’t come up. Maybe Cornelia had spoken to Gifford and insisted that for this luncheon at least, the topic was taboo. Or maybe both John and Gifford didn’t want to awaken any ghosts, and would rather remember their glorious campfire under the stars at the Grand Canyon.

And then I was suddenly startled out of my fly-on-the-wall reverie. Gifford pushed the floating bowl of fruit across to me and asked: “Bruce, what do you think of all this?”

I had been trying to keep up, to understand all of these comments in their context from the historical perspectives of an earlier time, and I was scrambling to do so. For five of the ten seconds it took for the bowl to cross the pool my mind went blank. Then for three seconds it protested: No! I’m just an observer, from the future, listening in on your conversations and debates. But there was no escape. I’d asked for this encounter with these spirits – at least one of them – and I couldn’t evade being part of the exchange of perspectives about the conservation of nature and natural resources across time.

“What do I think?” I stammered. “I’m… I’m humbled that you ask, and I just want to say, first, how grateful I am for all your efforts, your insights, your struggles, to bring us all, including me, to where we are now in our understanding of how we humans should relate to nature…” I was trying to buy time to think of what I thought, but I was feeling humbled, and I did think that each of these people here contributed, in their own context and time, and in their own way, to a better understanding of what we need to do.

“What do I think? I think we need a few things, all of which you have grappled with, and laid the foundation for. As you can tell, I’m a bit younger than all of you, and so what I think is colored by the changes that have happened since your time. In the current context, I think we need to keep working to understand ecosystems – this is the word we use now – in all their complexity as best we can, so that from that understanding we can try to manage them scientifically and sustainably, just as Gifford says. But we also need to understand – as Marsh warned – that Nature is so complex that we will never be able to completely understand and ‘manage’ her. I think we need to protect the few remaining examples of wild nature, the ‘witness stands’ that can provide a reference and laboratory to try to understand what Nature, not people, has put on each part of our Earth, as John has argued. And maybe most importantly, I think Cornelia is right when she says that the conservation problem is, fundamentally, about people – their needs, their aspirations, and their values. No amount of ‘scientific management’ will change people’s behavior toward Nature unless they see the value to their lives, whether as a source of wood to build their houses, or forest cathedrals to worship in. All across that wide spectrum, I think we need Nature, ecosystems, biodiversity. You helped us, each in your own way, to understand that.”

_____________________

It was a warm May afternoon. Maybe I had dozed off again. The bowl of fruit, almost empty now but with a few grapes and an apple left, was still floating on the Finger Bowl. I stood up and headed toward the parking lot. It had been an unbelievable, enchanting day at Grey Towers.

Sources and Related Links:

- Grey Towers National Historic Site

- Greenwood Furnace State Park

- Pennsylvania German Stoves: Mercer, Henry C. 1899. The Decorated Stove Plates of the Pennsylvania Germans

- Joseph Trimble Rothrock

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Rothrock

- Rothrock State Forest

- Cornelia Bryce Pinchot. Biographical article by Carol Severance (no date given)

- The Pinchot-Muir Split Revisited. 2007. Presentation at the Society of American Foresters National Convention, Portland, Oregon, October 26, 2007. Barry Walsh, Edward Barnard, and John Nesbitt, presenters

- Worster, Donald. 2008. A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir. Book jacked notes

- Worster, Donald. 1994. Nature’s Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas. Second Edition. Cambridge University Press

May 23, 2015 10:47 pm

It looks like a great place for a visit. How has your proposal to write up these trips/observations turned out?

Rich