November 2013. In the second week of November I found myself in Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, watching the ocean from a beachfront balcony. Last year at about this time I wrote about thoughts triggered by a hike in Nags Head Woods, a Nature Conservancy preserve nearby. On this trip I visited Nags Heads Woods again, and again pondered the ecological diversity of ponds scattered across the old dune landscape, now well forested and well back from the cutting edge of the dynamic coast. As I wrote last year, it is not clear to the casual ecologist why some of these ponds should be crystal clear, reflecting trees and sky like a mirror, and others completely covered with a green scum of duckweed, rendering them as unreflective as a putting green, although very striking in their own right.

This year I went for the first time to Fort Raleigh National Historic Site on Roanoke Island, which lies between the Outer Banks barrier islands and the mainland, and between Albermarle and Pamlico Sounds. This was the site of the first English attempt to colonize the “New World,” between 1585 and 1587, predating the Jamestown Colony farther north on the James River of Virginia by twenty years. It was a failed attempt, and the Roanoke colony is now lost in legend as the “Lost Colony.” The 118 English colonists left there in 1587 disappeared, never to be heard from again, and their fate is still the subject of speculation.

The first encounters between Englishmen and nature and native people on Roanoke Island were well documented by a gifted observer, mapmaker, and artist, John White, and a writer, Thomas Harriot. White produced a remarkable series of watercolor illustrations, 75 of which are now in the collection of the British Museum. Many of these were used as the basis for engravings made to illustrate Thomas Harriot’s account of their 1585 voyage, A brief and true report of the new found land of Virginia, which was published by Theodor de Bry in Frankfurt in 1590. Their paintings and writings provided the first information about the natural and cultural history of this New World to the English-speaking world.

The English were trying to catch up with the Spanish, who had a headstart of almost a century. The Roanoke exploration and colonization attempts were funded and sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh, under charter to Queen Elizabeth. No wonder Sir Francis Drake and other English “privateers” figure into this story; some, including of course the Spanish, would have called them pirates. Drake had been hanging out around Roanoke Island for some years on his voyages to prey on Spanish treasure ships, and when White and the first load of English colonists ran into difficulties in 1585, they accepted his offer to take them home to England.

Besides being the epicenter of a critical historical and cultural encounter between the Old and New Worlds, Roanoke Island lies on a biogeographical boundary, where ecological elements of the New World tropics reach their northernmost limits. Bromeliads, for example. The live oaks at the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site were hanging with “Spanish Moss,” Tillandsia usneoides, an epiphytic bromeliad. Of the approximately 3,200 species in the plant family Bromeliaceae, all but one are found in the Americas, and mainly in the Neotropics. Only a few species range northward into the subtropics of northern Mexico and the southeastern United States. Spanish Moss is the bromeliad with the northernmost range of all, reaching the Outer Banks, and barely beyond to the tip of Virginia’s Delmarva Peninsula.

John White painted another bromeliad, the pineapple, which he first encountered in the West Indies on his way to Roanoke Island in 1584. He labelled his painting “The Pyne frute.” This unique edible bromeliad is thought to have been domesticated in southern Brazil and spread northward during pre-Columbian times. White’s illustration was the first English encounter with the Bromeliaceae.

And alligators are here near the Outer Banks, just barely: the Alligator National Wildlife Refuge, on the North Carolina mainland just to the south and west of Roanoke Island, is approximately the northern limit their range. White also illustrated this species, which he labelled “Allagatto.” His watercolor shows a young, thin individual, which he described saying “This being but one moneth old was 3 foote, 4 ynches in length.”

White painted fireflies, which must have seemed magical: “A flye which in the night semeth a flame of fyer,” he described them.

The brown pelican attracted his attention. He illustrated the amazing fish-catching throat pouch of this species, and labelled his painting “Alcatrassa,” using its Spanish name “alcatraz,” saying “This fowle is of the greatness of a Swanne, and of the same forme saving the heade, wch is in length 16 ynches.” He painted more than a dozen fish, including flying fish and puffer fish, dorados and grunts. He painted hermit crabs, scorpions, flamingos, crabs, box turtles, and the loggerhead sea turtle. His painting of a tiger swallowtail is the first illustration of a North American butterfly.

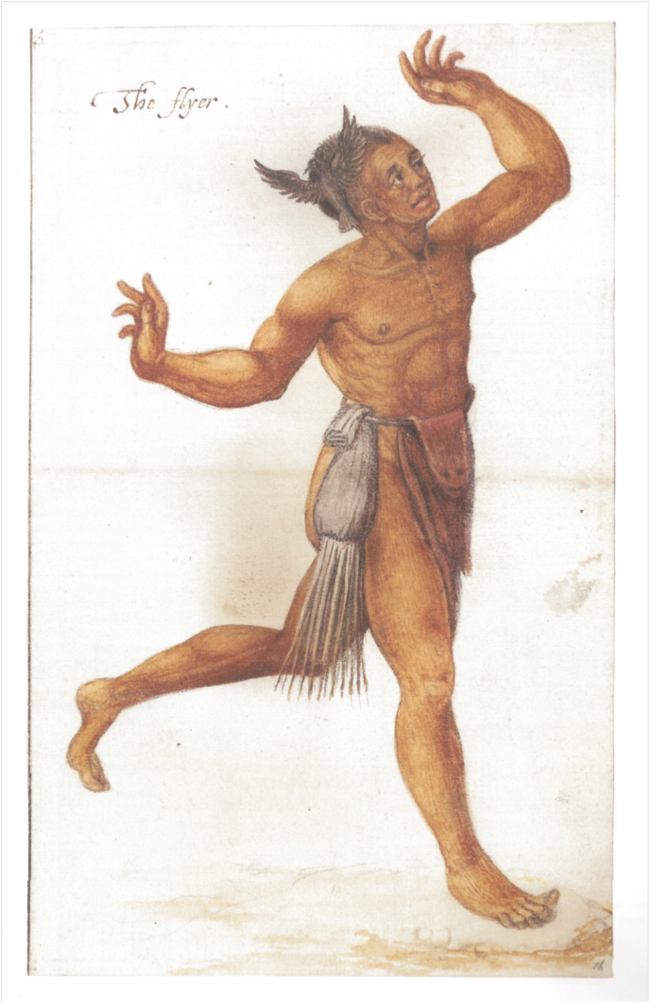

Perhaps more thought-provoking to 16th century Europeans than White’s pictures of plants and animals were his portraits of the native inhabitants of Roanoke Island. His sympathetic, humanizing images of the local people, their villages, their economic activities, and their ceremonies seem, at least to a modern eye, to portray them as equals. The paintings show them as people with a sophisticated knowledge of their environment, which then was so foreign to Europeans, and of how to make a living in it – knowledge that the first colonists lacked almost completely.

His portrait of a local shamen, labelled “The flyer,” strikes me especially. The painting shows a well-built man, mostly naked except for an animal skin apron and fringed bag hanging from his belt, who seems to be running through the air – almost flying – with his fingers spread in way that reminds me of how the wingtip feathers of hawks, ravens, and condors spread when they are feeling the currents of air through which they fly. He wears a bird with its wings outspread as a headdress above his right ear. His expression seems otherworldly, fixed on the future, the big picture.

In his equalizing images of indigenous Americans, White reminds me of Alexander von Humboldt, whose reports of his explorations in South America in the 18th Century painted a picture of cultured and sophisticated New World civilizations deserving of European respect. In this regard, White was more than two centuries ahead of von Humboldt, who himself was far ahead of his time. But this illustrates an interesting insight into the slowly shifting European worldview of White’s time. In the 16th Century, humanist influences were penetrating the old, inbred worldviews of Europe. White was a contemporary of William Shakespeare. The Age of Exploration was opening up the world, and opening up at least some European minds. Some of the gentlemen-courtiers with whom he kept company were not only interested in economic opportunities in America, but also curious about the land and people of the world in a broader sense. Although White and other explorers were commissioned to describe all that they saw and learned that was of potential commercial value, he obviously couldn’t resist his own natural curiosity. While pineapples may fit within that mercenary mandate, fireflies and butterflies do not. And in this, we might interpret White as among the first in a line of curious geographers and artist-naturalists, whose later ranks include Von Humboldt, William Bartram, John James Audubon, Charles Darwin, Alfred Russell Wallace, and John Muir.

White’s illustrations provide a remarkable and tantalizing record of the first deep encounter between England and the people and nature of the “New World.” The Outer Banks and nearby mainland where White made these observations are a biogeographical boundary where elements of the flora and fauna of South America encounter and intermingle with those of North America. And because of continental drift, that biogeographical boundary also reflects a re-contact between ecological elements of Laurasia and Gondwana, the long-separated northern and southern siblings of the former supercontinent Pangaea.

The encounter between people and nature is continuing today here around the Outer Banks. The system of national wildlife refuges in this area, including Alligator River, protects the last wild population of the red wolf, Canis rufus, a relative of grey wolves and coyotes, whose historic range was the southeastern U.S. The many refuges here, from the Great Dismal Swamp to Mackay Island and Pea Island are important stopovers for migratory birds, moving between north and south.

Watching the ocean from my beachfront balcony, flights of pelicans passed, sometimes from north to south, sometimes from south to north. They glided over the wavetops, riding the updrafts along the wave fronts, flapping their wings only when necessary. Sometimes one would break away from the flock and flap up, looking down, and then plunge into the sparkling water after a fish.

For last year’s blog about the Outer Banks, read Pondering the Ponds of Nags Head Woods and about early American naturalists John and William Bartram and John James Audubon.

Related links:

- A New World: England’s First View of America, by Kim Sloan. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill. 2007.

- Fort Raleigh National Historic Site

- Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge

- Red Wolf Recovery Program

- Red Wolf Fact Sheet

December 15, 2013 1:44 am

Very thoughtful writing Bruce. Historical context and images were a great treat. I greatly enjoyed this post and will ponder your insights when we head down to the Outer Banks after Christmas for a few days. Thanks!

December 21, 2013 5:13 pm

Glad you enjoyed this little story, Matthew, and thanks for the comment. If you have time when you are at OBX after Christmas, check out Fort Raleigh. Or look for tundra swans and snow geese at Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge. Or for a real adventure, try howling up some red wolves some night at the Alligator River NWR.

December 16, 2013 11:28 am

Gracias, amigo por ayudarme a enriquecer conocimientos; Muy interesante.

December 21, 2013 5:15 pm

Gracias, Victor, por tu comentario. Estoy muy contento que disfrutaste este cuento. Y muchas gracias a ti por la ayuda a conocer un poco de la naturaleza del sur de Honduras. ¡Muy impresionante!

October 18, 2014 7:13 pm

Thank you for this lovely blog entry and most especially sharing the artwork. I am currently reading Roanoke : Solving the mystery of the Lost Colony, by Lee Miller, and, while there are wonderful descriptions of White’s work, none of it is included in the illustrations in the book.

I did a Google search, looking particularly for the baby alligator, and discovered your blog!

Thank you again – I will definitely have to plan a trip to the Outer Banks some time in the future.