August 2014. What I liked so much about Point Reyes when I first started hiking and camping there as a college undergraduate was that it combined natural ecosystems and human uses in a beautiful mosaic, a “working landscape,” a balance of people and nature. Dairy farmers and oyster-growers made a living there, and dark coastal forests and elk thrived too. Point Reyes was a national seashore, not a national park, established in 1962 for a mix of compatible, sustainable uses. Threatened by coastal development, local dairy farmers, beef ranchers, and conservationists had teamed up to push for its designation and management as a multiple-use landscape, including natural ecosystems, pastoral lands, and a historic oyster farm on Drakes Bay.

Back then, after reading about the geology of Point Reyes in Roadside Geology of Northern California, I collected a piece of weathered granite from near the Point Reyes Lighthouse, and it sat on my desk as a paperweight for many years, my daily reminder of the dynamic, continentally-drifting planet we live on. According to geologists, that piece of rock from Point Reyes matches rocks found on the other side of the San Andreas Fault near Santa Barbara, now around 350 miles south.

In a lovely essay “Crowning Glories: 50 Years of Point Reyes,” Jules Evens described the geology of the place: “The Point Reyes peninsula was dubbed an “Island in Time” by San Francisco Chronicle writer Harold Gilliam, a sobriquet that captures both the singular and transitory nature of the peninsula – a huge chunk of granitic bedrock wrenched from the southern Sierra Nevada about 100 million years ago and adrift ever since, working its way up the coast, pushed along by the tectonic forces generated by the perennial collision of the North American and Pacific plates. This itinerant geology is sutured, if temporarily, to the western boundary of the North American tectonic plate. The expression of this contact zone, the San Andreas Fault, comes ashore at Bolinas Lagoon, stretches northward beneath the deceptively tranquil Olema Valley, and heads offshore again at the mouth of Tomales Bay. This plate boundary is considered “active,” and the northwestward movement of the Pacific Plate is relatively speedy in geologic time, averaging two to three inches a year, but predisposed to much more abrupt jolts when the fault gives way, as it did in the great 1906 earthquake, which left visible scars in the landscape around Olema.”

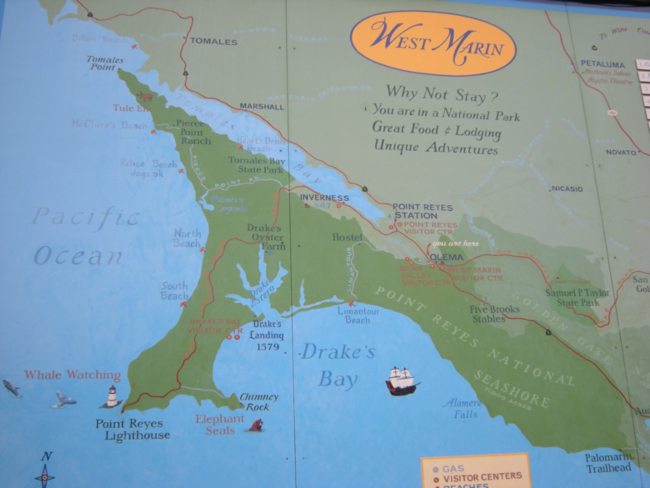

Fast forward to the “Island in Time” today. Tule elk populations, once considered endangered, have rebounded, especially on Tomales Point, the northern tip of the peninsula, where they now probably exceed the carrying capacity of the habitat. The entire “West Marin” landscape has experienced a recreational and foodie boom, providing an accessible rural and natural getaway for the urban throngs of the San Francisco Bay metropolitan area.

Now, these many decades after my first visits, Point Reyes National Seashore is a case study of the schizophrenia in American conservation philosophy. This was one of the things that I’d come to California to explore on a trip this past August. In several previous stories about that trip, I reflected on John Muir, and his influence on American conservation, and about Robinson Jeffers, whose “not man apart” philosophy had a strong influence on some of my ecophilosophical ancestors, and on me.

So what’s the issue? Why do I say “a case study of the schizophrenia in American conservation philosophy”? It’s about oysters. Specifically, the Drakes Bay Oyster Company. Their case to retain the right to grow oysters in the National Seashore went to the Supreme Court this year under appeal; the Court refused to hear the appeal, letting a lower court ruling stand. The National Park Service and some people’s idea of “wilderness” won, oysters and working landscapes lost. The case shines a bright light on the still unsettled state of our understanding of, and public policies toward, the relationship between humans and nature.

Sign supporting the Drakes Bay Oyster Company

The relationship between humans and nature. In my career over the last twenty years I’ve worked in more than thirty developing countries, where the urgent need is to find ways to conserve nature in working landscapes, the places where people produce food and make a living. Ironically, I’ve often thought of Point Reyes as a potential model.

A decade or so after my early Point Reyes days, I had a chance one summer to experience some of England’s “national parks.” According to the UK National Parks website, “There are many different types of protected areas across the world. The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) has split them into six categories. Even though the IUCN call Category II ‘National Parks’, the UK’s National Parks are actually in Category V.” The IUCN defines Category V protected areas as “A protected area where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced an area of distinct character with significant ecological, biological, cultural and scenic value: and where safeguarding the integrity of this interaction is vital to protecting and sustaining the area and its associated nature conservation and other values.” The primary objective of such protected areas is “To protect and sustain important landscapes/seascapes and the associated nature conservation and other values created by interactions with humans through traditional management practices.”

Point Reyes National Seashore was clearly founded as an IUCN Category V protected area. But the Department of Interior opted not to renew the lease of the Drakes Bay Oyster Company, pushed by some factions of the environmental movement who want to incorporate the Drakes Estero area into the part of the National Seashore designated as “wilderness.” In their efforts to do so, they portrayed the options to the public as a clash between “wilderness” and compatible human uses of nature. This led to the appeal that went all the way to the Supreme Court.

What we need now, in all countries – both developed and developing – are models of how to integrate humans into functioning natural landscapes, landscapes that balance the conservation of biodiversity, on which everything depends, with our need to eat and make a living. What we need now, in other words, are models of successful IUCN Category V protected areas.

We need those models far more than we need models of how to protect wilderness areas “untrammeled by man,” as the classic U.S. definition of “wilderness” has it. That definition poses a dichotomy between landscapes “where man and his own works dominate the landscape,” and those “where the earth and its community are untrammeled by man, where man is a visitor who does not remain.” No: what we really need are models of where neither of these dichotomous poles dominates, but where humans and their economic activities are balanced with the Earth and its ecosystems. Point Reyes should be that. In losing its only oyster farm it may have lost a precious chance to be one of those badly-needed models of a balance between humans and nature.

Besides losing this model of integrating human uses into conservation landscapes, the philosophical wound may be deeper. Ironically, pushing a historic oyster farm out of Drakes Bay may be treating man as “apart” from nature, as not a part of nature. In a strange, twisted way, the idea of a “pure” wilderness – some sort of perfect, untouchable, supposedly “wild” nature – is a dualistic view that in the end is probably counter-productive for the conservation of nature. Pure wilderness isn’t what my ecophilosophical ancestors Ed Ricketts and John Steinbeck, following Robinson Jeffers’s “not man apart” philosophy, were envisioning about the proper relationship between humans and nature. And it is very ecologically naïve: ever since humans arrived in North America perhaps some 15,000 years ago, there has been no “wildness” or “wilderness” that wasn’t shaped by, and didn’t include, our species as part of it. From megafaunal extinctions to the shaping of forests by anthropogenic fire, we have been part of “wild” North America for millennia.

Sitting on the continental side of the San Andreas Fault, at the Hog Island Oyster Farm in Marshall on the east side of Tomales Bay, I washed these thoughts down with another cold, tangy, just-shucked oyster, and a sip of a hoppy local IPA from the Lagunitas Brewing Company in Petaluma. I could taste the whole ecosystem: the cold currents and fogs; the nutrients washed from the ridges of forests and elk and dairy farms; the marine mammals – seals, sea lions, whales – and birds; the tourists from the cities who come to restore their connections with their home planet.

To think that getting rid of an oyster farm is somehow “better” than leaving it as part of an integrated working landscape is treating humans and nature as independent, separate entities. To paraphrase Jeffers, in the spirit, I think, in which he wrote his “not man apart” lines:

The greatest beauty is organic wholeness… Love that, not nature apart from that.

Nature can never be apart from humans, and vice versa – and it’s anthropocentric to think that we could ever be separated.

For related stories see:

- All I Came to Seek I Found: Closing the Loop with John Muir in California

- At Church with John Muir

- Not Man Apart: Genealogy of an Ecological Worldview

Related links:

- Point Reyes National Seashore

- Crowning Glories: 50 Years of Point Reyes. Jules Evens, July 02, 2012

- Drakes Bay Oyster Company

- “What you may not know about the laws governing Drakes Estero,” Dr. Laura A. Watt, 2010.

- National Parks, Britain’s Breathing Spaces: What is a National Park?

- IUCN Protected Area Category V

- Hog Island Oyster Company

- Lagunitas Brewing Company

October 31, 2014 3:44 am

Look forward to talking with you about this piece and related things.

October 31, 2014 3:46 am

Bruce,

I liked this. We’ll have to talk about it and related topics when we next see you.

Dewey

October 31, 2014 12:02 pm

Both Jeffers and the other great West Coast poet, Gary Snyder, saw mind and nature as indistinguishable. The Drakes Bay debate, an instance of the insurgent ecological phenomenon of “rewilding”, represents the sharp break between mind and nature in modern America. Snyder, a Buddhist, argued eloquently for a reconciliation in his 1969 protest poem, the Smokey the Bear Sutra (http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Smokey_the_Bear_Sutra). If you haven’t read it, you’re in for a treat. Wilderness as a concept reifies the split. This is a lesson that West Africa taught me. There, human society is the source of purity and warmth, and nature is chaotic, menacing, malevolent. Both world views represent false dichotomies that are barriers to sustainability. Thanks for sharing.

August 10, 2022 8:12 pm

Your particular reading of particular lines from Jeffers rather ignores his misanthropic view. “Man has bred knives in nature and turns them also inward” is another quote—and a far more accurate representation of his view of humanity as self-entitled and destructive of the natural world. In the instance if Drake’s Bay Oyster Farm, run through with capitalism’s conceits, all the way to the climate crisis, Jeffer’s view seems to have been accurate. The instructive “oneness” he sought, ironically present only where we do not remain, seems always to escape humanity when dollars comes first.

August 11, 2022 8:14 pm

Paul, Thank you for your comment on this old post! I’ve recently been working on a book of essays about Point Reyes and the larger Golden Gate Biosphere Reserve (look for that in about a year). My views about the oyster farm have shifted since I wrote that story you commented on, and I now think not allowing it to continue operating was the right decision. My views on Jeffers have not changed, however, and I think you are reading him wrong. I don’t think he was “misanthropic,” but rather trying to call us to our better, higher, natures; his “inhumanism” is not the same as misanthropy. You may wish to look at an old article of mine in The Trumpeter, from 1992, titled “Deep Ecology and Its Critics: A Buddhist Perspective,” linked on the library page of my website: http://www.brucebyersconsulting.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Deep-Ecology-and-Its-Critics-The-Trumpeter-Win.-1992.pdf