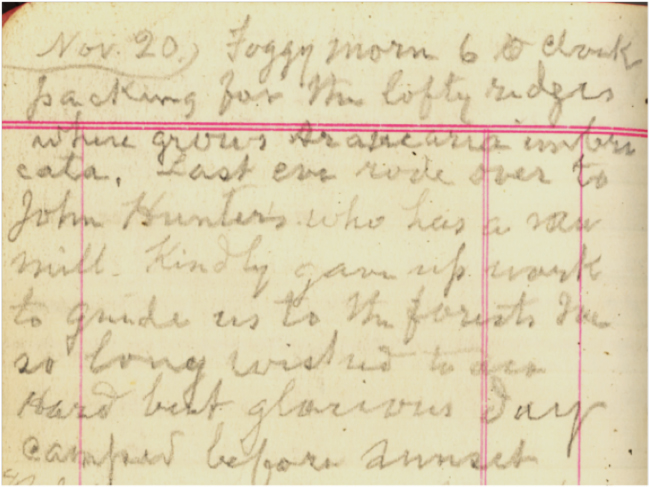

April 2016. In his journal entry for November 20th, 1911, John Muir wrote: “Foggy morn 6 o clock packing for the lofty ridges where grows Araucaria imbricata.” He had arrived in Victoria, Chile, on November 14th, and after being delayed for several days by heavy rain, was finally riding toward the mountains to the east where he hoped to see forests of Araucaria araucana, the monkey puzzle tree (a taxonomic revision has changed the scientific species name from imbricata to araucana since Muir’s day).

Fragment of Muir’s journal from 20 November, 1911 (used with permission of the John Muir Papers, Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific, Stockton, California)

In 2013, on our second research trip to reconstruct Muir’s route to the Araucaria forest he finally found, we finally found the great-grandson of Philip Smith, a Canadian immigrant to Chile, who hosted and guided Muir to see his “long sought for” monkey puzzles. Philip Smith had come to Chile in 1887 with his eldest son George, as a salesman for steam-powered sawmills made by the Watrous Engine Works of Branford, Ontario, Canada. Harry Smith, Philip’s great-grandson, shared family information and old photographs with us.

It was from Harry that we learned that Philip Smith’s country estate, or “fundo,” which Muir called the “Smith Ranch” in his journal, was called by the family “Fundo Ontario,” named for their home province in Canada. That information led us to a parcel of land east of Victoria, still called “Ontario,” where Muir slept for two nights before riding for the mountains. In his journal on November 19th, Muir wrote: “I wandered through broad wheat fields a mile or two from the ranch house and obtained magnificent views of eight great white volcanic cones, ranged along the axis of the mountains. Spent the day sketching them. Sketched all in outline,” In the fields around Ontario in 2013 we found the places from which Muir made his sketches of those volcanic peaks to the east.

Volcán Tolhuaca (top) and Volcán Lonquimay from Fundo Ontario, March 2013, compared with Muir sketch (used with permission of the John Muir Papers)

——-

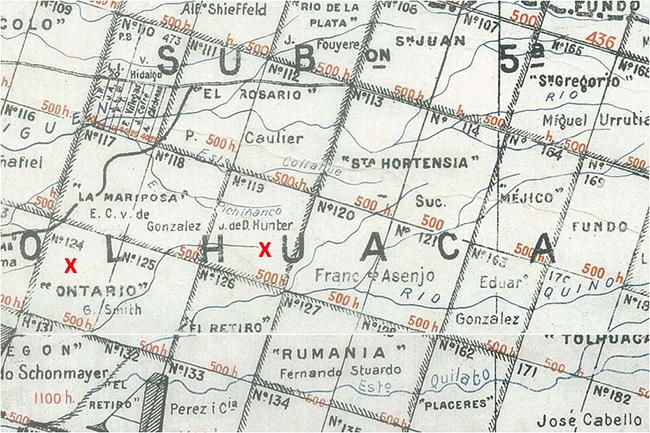

Since our 2013 trip, some detective work by our forest-ecologist colleague from the University of Concepción, Aníbal Pauchard, had turned up an old map from 1917 that showed the locations of all of the properties in the area. The map showed how close the Fundo Ontario was to the Malleco Forest Reserve, the first protected area in Chile, established in 1907 through the efforts of Federico Albert (more on Albert in another story). The map showed the valley of the Río Malleco and Laguna Malleco – the valley and meadow above a “big lake” in Muir’s sketch made on November 20th, the day he and his companions rode to the site where they camped under Araucarias. “Hard but glorious day. Camped before sunset,” Muir wrote in his journal entry.

Detail from 1917 map of property owners in Malleco Province, Chile. Red “X” marks location of Fundo Ontario.

——-

We left Suizandina Lodge on another “foggy morn,” April 6th – a good bit later than Muir’s 6 AM departure time though, after a hearty breakfast and plenty of coffee. We wanted to go back to Ontario and look for the old “Smith Ranch” house where Muir stayed. On our trip in 2013, we had been too busy looking for the sites from which he sketched the volcanoes, and talking to Marcelo Mila, the leader of the community of indigenous Mapuche who now live at Ontario, to look for the old house. This time Marcelo wasn’t around, but we talked to his neighbor Robinson, who described how to find it.

It looked like someone was living there. Bright laundry hung on a line in the back, and turkeys, chickens, and ducks foraged in the bare yard. Not wanting to be too intrusive, we parked at the bottom of the driveway, and walked up. A lonely Araucaria grew beside the faded old house, which had peeling white paint and a rusting metal roof. We knocked at the door and hollered “hola” several times. Apparently whoever was living here was away just now.

We had found the “Smith Ranch” house where Muir slept for several nights. We wondered which was the window of his guest bedroom.

In Muir’s journal entry of 20 November, describing the day of travel to the mountains, he had written: “Last eve rode over to John Hunter’s who has a sawmill. Kindly gave up work to guide us to the forests I’ve so long wished to see.” On that foggy morning, heading for the mountains, Muir wrote that ““Our party consists of Mr. Smith, Mr. Williams, Mr. Hunter, Self & 2 Chilean packers.” Studying the old map showing the owners and locations of the properties at the time Muir visited, we realized that an old house we had found and photographed in 2013 was John Hunter’s house, just over the gentle ridge that slopes down into the upper valley of the Río Traguen, only a mile or so from the Fundo Ontario. We drove over to see it again.

Detail from 1917 map of properties in Malleco Province, “X”s mark the Fundo Ontario and John Hunter parcels.

We have been trying to find answers to multiple mysteries surrounding Muir’s trip to Chile, and John Hunter figures into one of them: the mystery of what happened to photographs of the Araucaria forest that Muir mentioned in his journal entry of November 21st. On that day he wrote: “I traced the south ridge above our camp, sketching and photographing six views of the ancient forest.” This sentence implies that Muir himself was taking photographs. It is possible that he had a camera with him on the trip. After all, “kodaks” were common by the time Muir joined the Harriman Alaska Expedition in 1899, and his daughter Helen was photographing her father and sister in the Petrified Forest of Arizona in 1905, so personal cameras were familiar to the Muir family even then. But any photos Muir may have taken apparently did not survive his trip, which included another six months of travel through Africa before he returned to California. Or, the other possibility is that John Hunter, one of his hosts, was taking photographs for – or in addition to – Muir.

I’ll return to the mystery of the missing photos in a moment. But we, and others, have also puzzled about why Muir didn’t publish anything about his South American and African travels in the two and a half years between his return and his death in 1914. One explanation is that he was consumed during those years with the final stages of the fight against Hetch Hetchy Reservoir in Yosemite National Park. But Michael Branch, editor of John Muir’s Last Journey – the annotated transcription of Muir’s journals from his trip to South America and Africa – doesn’t think that explanation is sufficient. Another reason for Muir’s delay appears to have been his effort to get photographs to illustrate the articles he was planning to write.

Branch relates how Robert Underwood Johnson, Muir’s long-time, faithful editor at Century Magazine, had solicited articles even before Muir left on his last journey, and pressured him for them as soon as he returned. Muir began working on his journal notes almost immediately after his return to California in the spring of 1912. Visiting his daughter Helen in Hollywood, he had his journals typed up by a secretary that summer. But by that time photographs were becoming expected as illustrations in magazine articles, and Muir was conflicted and stymied by a lack of photographs from his trip. In August, 1912, he wrote to Johnson at Century that although he had all his travel notes in order, “… I find that without a lot of good photographs suitable magazine articles cannot be got out of them, at least in a reasonable time.” Oh, I understand it perfectly – as you can see from my use of photos to tell the story in these stories! “A picture is worth a thousand words,” as the saying has it.

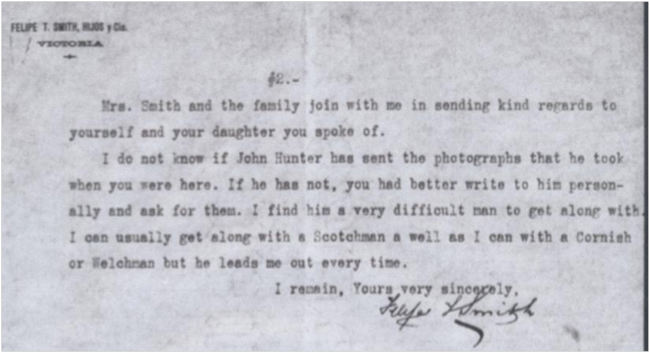

Muir tried to salvage the situation by soliciting photos from people he had visited. He must have written to his host in Chile, Philip Smith, asking about photos of their trip to the mountains, because in an answering letter Philip Smith says: “I do not know if John Hunter has sent the photographs that he took when you were here.” So Hunter must have been taking photos on the trip to the mountains, even if Muir was also. And this letter exposes the rift between Philip Smith and John Hunter, which Harry Smith remembers as family history to this day. Philip’s letter to Muir continues: “If he has not, you had better write to him personally and ask for them. I find him a very difficult man to get along with. I can usually get along with a Scotchman as well as I can with a Cornish or Welchman but he leads me out every time.”

Detail from letter to John Muir from Philip Smith, June 3rd, 1912. (used with permission of the John Muir Papers)

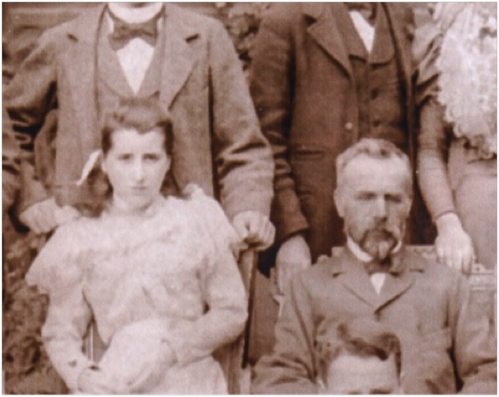

This tension between Philip Smith and John Hunter may have had a very personal dimension. We learned from Harry Smith that John Hunter married Philip’s youngest daughter, Elizabeth. Oh, who knows the real story? Elizabeth – Lizzy – rebellious youngest daughter, falls in love with an older neighbor who her protective father doesn’t really like? Maybe. Probably. Yes, it seems that is what happened.

Some of John Hunter’s descendants emigrated to Australia, although there are still some “Hunters” in the telephone directory in and around Victoria, Chile. Harry Smith sent us a photo of John Hunter from 1936 that he got from his Australian relatives, with the note “I am sending the photograph of my great uncle John Hunter, which I received the other day from Australia, hope it is O K. He is much older, as it was taken in the thirties.”

Photo of John Hunter, taken at the port of San Antonio, Chile, 1936. (photo courtesy of Harry Smith)

It turns out that Muir had already written to Hunter about the photos. Michael Branch quotes a letter from Hunter to Muir, dated 24 April, 1912, saying that he had sent ten photographs, but that “I have overexposed the plates; that is the cause of the fog.” Apparently these photos did not meet Muir’s expectations, or magazine standards, and they too appear to have been lost.

Alas, it’s a bit like the quotation attributed to Benjamin Franklin “…for want of a shoe the horse was lost, for want of a horse the rider was lost…” For want of a good photo of the Araucaria forest he had seen – and despite his beautiful sketches of them – Muir’s motivation to publish something about his experience faded under the then-modern expectation of photo-illustrated magazine articles. And so we are left imagining what he felt, and would have said, if he had written a popular article about his trip to the monkey puzzle forest with Philip Smith and John Hunter. We are left wondering what he meant when he wrote to his friend Henry Fairfield Osborn in late November, 1911, waiting in Buenos Aires for a ship that would take him to Africa, the second leg of the last major journey of his life: “All I came to seek I’ve found and far, far more.”

We did manage to find the old house at Fundo Ontario where Muir slept before and after his success in seeing an Araucaria forest, and John Hunter’s old house as well. But we are still hoping that somewhere in a closet or attic in Australia or Chile, or maybe even in California, an undiscovered box of old photographs, maybe glass-plate negatives, will turn up – photographs of Muir sketching under the Araucarias he went so far to find. Until then, we can only imagine.

For related stories see:

- Tracking John Muir to the Monkey Puzzle Forests of Chile

- Following Muir’s Route in Sketches and Photos

- Documenting Forest Change at the Muir Site

- Maples, Mapuches, and Monkey Puzzles: Human Dimensions of John Muir’s Travels in Chile

- Picnicking in Deep Time

- Following John Muir’s Footsteps in the Petrified Forest

- All I Came to Seek I’ve Found: Closing the Loop with John Muir in California

- Following Up on Following John Muir to the Monkey Puzzle Forests of Chile

Sources and related links:

May 29, 2016 4:17 pm

Bruce:

As always, I enjoyed this little story about Muir’s search for Araucarias in Chile. Some place I once read that Muir was truely devastated by the impending damning of Hetch Hetchy and I’ll bet that so completely consumed his time and was why he never wrote his promised article on his trip to Chile and South Africa.

—Sid

March 27, 2019 5:52 pm

Most interesting, thrilled to know more about the history of “Fundo Ontario”, and see photos of the old house, the farm ended up un my grandfathers hands in the 1920’s and till today I remain owners of one of its parcelas.