October 30, 2013. Just after the death of his wife Louie Strenzel Muir in August, 1905, seeking to escape his grief and find relief for his youngest daughter Helen’s tuberculosis, John Muir travelled with his daughters to eastern Arizona. They settled in at the Forest Hotel, a small tourist establishment in Adamana, a coaling and watering station on the Santa Fe Railroad, near an area of exposed fossil trees that would a year later be declared the Petrified Forest National Monument by Muir’s friend, President Theodore Roosevelt. They stayed in Adamana almost a year. Muir provided sketches of boundaries to the federal government that would help define the new monument, according to his biography by Donald Worster.

Adamana is now more or less a ghost town, just south of Interstate 40, not far east of Holbrook, Arizona. The hum of big trucks rolling the interstate is a constant background of white-noise here.

In my previous story I wrote about our search for fossil fire scars in the Petrified Forest. We also wanted to follow Muir’s footsteps, if possible, and were again aided in this quest by the park paleontologist, Bill Parker, who provided us with a handful of historical photographs of the sites Muir visited in 1905.

Historic photo of John Muir in the Petrified Forest

In 1888, Frank Knowlton, the Assistant Curator of Fossil Plants at the U.S. National Museum, looked at some fossil logs that had been hauled to Washington from the northern “Black Forest” area of the current park in the early 1880s. He decided that these were ancient conifers that looked much like trees in the modern family Araucariaceae, and named them “Araucarioxylon arizonicum” – essentially the Latin translation of “ancient Araucaria of Arizona.” A more recent paleo-taxonomic revision has suggested that the ancient genus of these trees is more appropriately called Agathoxylon. Agathis is another genus in the Araucaria family.

Muir, a well-trained botanist, was probably aware that relatives of the giant fossil trees he saw in Arizona still grew on the southern continents, and seems to have been fascinated by the Araucariaceae, modern and ancient. On a tour to Australia and New Zealand in 1904, he made deliberate detours from a more direct route of travel to see Araucaria bidwellii , the “bunya pine,” in the rainforests of Queensland, and another giant member of the Araucaria family near Dargaville on the North Island of New Zealand, the kauri, Agathis australis. In 1911, when he was 73 years old, he travelled alone to Chile to look for Araucaria araucana, the Monkey Puzzle Tree, in its native environment. I’ve written in several earlier stories about following his footsteps to the exact spot on the side of Volcán Tolhuaca, where he finally saw this species. It was exciting to be following Muir’s footsteps again, this time on an earlier journey – into the fossil “forests” of the Late Triassic.

Araucaria araucana on “Muir’s Ridge,” looking toward Volcán Tolhuaca, Chile, February 2012

Historic photo of John Muir in the Petrified Forest

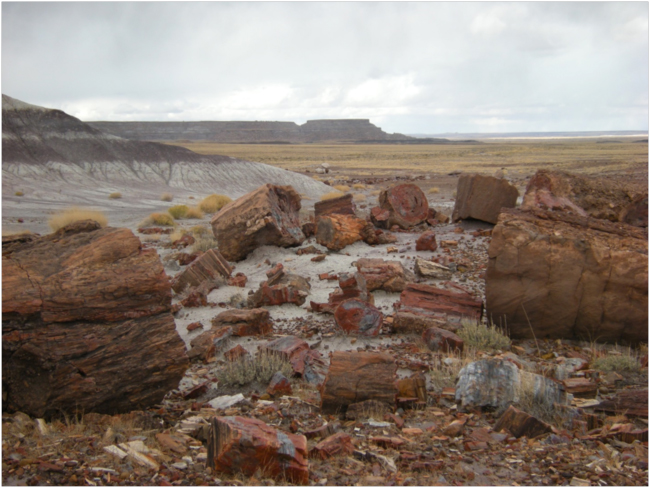

As we headed on foot and off-trail through the Jasper Forest, the wind was howling. It was mostly overcast, and off to the west the low, fast-moving clouds looked like we might soon get some rain, or snow. Our destination was an area that was called the “First Forest” in the early 1900s because it was the first of the big deposits of fossil trees that could be reached from Adamana, only about six miles away. With prints of the historic photos gripped tightly in gloved hands, we stumbled around trying to match up bluffs and cliffs on the horizon and the slopes and forms of the landscape nearby. When the photos and our views began to match, we searched for pieces of fossil logs with the shapes and positions of those in the photos. When we found the first “match,” we knew we were in the area where Muir and his daughters had been, and guessed that at least some of the other photos might have been taken nearby.

The first matching location we found was perhaps the easiest, because of the distinctive shape of the mesas on the northwest skyline, and a promentory of white and purple badlands in the middle distance. It was a strange feeling to stand on the exact spot where the photo we held in our hands was taken almost a century ago. A few of the giant sections of fossil logs had shifted their positions since Muir was looking at this same scene, but only very slightly. A log that stood vertical in the center of the old photo had toppled to a horizontal position. And the tongue of purple and white mudstone on the left side of the photo had clearly been eroded by a few feet. There was some geological change, but it had been very slow.

Copy of the historic photo from 1905, weighted with pieces of fossil wood, on the exact spot from which it was taken

Rephotograph of “In first forest”

Not far away we found the location of another photo. The caption said “In first forest – looking north.” Again, some minor movement of the fossil wood could be detected by comparing the photo and the modern view. The two big logs in the left foreground had moved a foot closer together, and were now touching. But not that much had changed in a century.

“In first forest – looking north,” historic photo from 1905 with caption apparently by Helen Muir, “H.M.”

In first forest – looking north, rephotograph, October 30, 2013

In the same area we finally spotted the scene we especially wanted to rephotograph. The 1905 photo shows five people: John is pointing at a ring-like crack in the end of a fossil log. Behind him, a mostly-hidden man with a hat lays his right hand on the ancient log. A woman and man behind them are conversing intently. The woman dominating the right side of the photograph holds a chunk of fossil wood in her left hand, and appears to be examining another in her right hand more closely. The women are presumably Muir’s daughters Wanda and Helen, both wearing similar unique hats, although it is impossible to tell which is which. For an August expedition in the Arizona desert, all of them look overdressed. I imagine they were perspiring profusely under those long sleeves and layers.

Muir and his daughters examining a fossil log, First Forest, 1905

Bruce and Anya examining a fossil log, First Forest, October 30, 2013

Meanwhile, as we tried to re-enact the scene, we were pelted by light rain, thrashed by wind, chilled to the bone, and treated occassionally to a pulse of sun breaking between the fast moving clouds. The sunlight and shadows playing over the stark landscape were enchanting.

The ground here in the First Forest is a desert pavement of shards of fossil wood of all colors, although the dominant color is rusty red. The close-up landscape underfoot was as amazing as the larger view. No wonder Muir was fascinated by this place.

Chip of fossil wood, First Forest

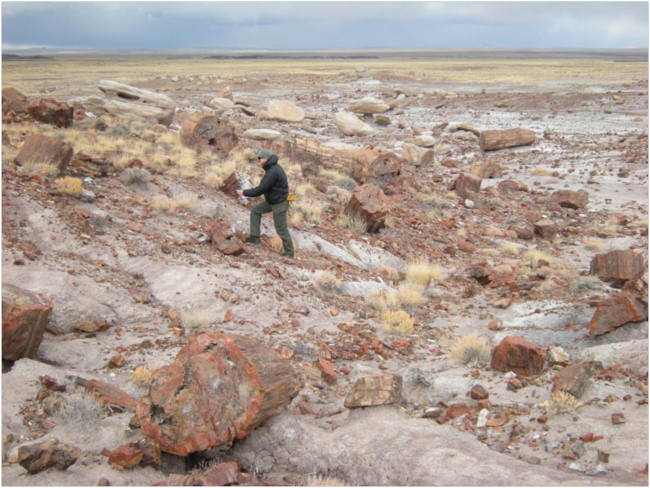

Wandering farther, we found the sites of two more historic photos from Muir’s time. One looking north from First Forest toward Adamana showed two men, one scrambling up a slope among fossil logs. Again we wondered at how hot they must have been in August, 2005, as we re-enacted the scence with pellets of ice pelting us from the next passing shower.

In first forest in August, 1905

James re-enacting the scrambling man in the historic photo, October 30, 2013

After returning from this trip to the Petrified Forest, I was looking at some old slides my dad took. Although I can’t remember it, according to these photos I was also there many years ago. One photo shows my mom holding my hand by a section of a fossil tree, and in another I’m sitting on a big fossil log.

My first visit to the Petrified Forest

Native Americans wondered about these stone logs lying in a treeless desert landscape and explained them through their myths and stories. According to an 1876 report by John Wesley Powell, the Paiute of the area said they were the arrow shafts of the Thunder God, Shinuav, which may suggest that they recognized their similarity to modern wood. The first American explorers who saw them must have wondered too. The first sketch of a fossil tree was published in the 1855 report of the Whipple Expedition, and in 1878 two sections of fossil logs were sent to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, where they are still on display. Later travellers, tourists, and scientists – including John Muir – were pulled here by the sense of wonder about these ancient trees. And even if I don’t consciously remember being in the Petrified Forest when I was two years old, something about it must have entered my memory, so that being there again resonated deeply. Something about the depths of time, and the dramatic changes that have occurred on Earth, and also about how our lives are somehow a part of all that.

For previous stories about following John Muir’s 1911 journey to Chile, see:

- Tracking John Muir to the Monkey Puzzle Forests of Chile

- Maples, Mapuches and Monkey Puzzles: Human Dimensions of John Muir’s Travels in Chile

- Following Muir’s Route in Sketches and Photos

- Documenting Forest Change at the Muir Site

Related links:

- Frank Knowlton’s 1888 paper describing Araucarioxylon arizonicum

- A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir, by Donald Worster. Oxford University Press. 2008.

December 7, 2013 3:05 am

Great photos and article, Bruce. But tell me, are Muir’s daughters wearing cheese-head hats? Were they U. Wisconsin fans, or was that protective headgear fostered on them by the National Park Service (in case of an errant petrified limb)?

Timberrrr ….

Also, I love the purple pants on your first visit. Stylish, even then. You look so happy with your Mom, on the dunes, amongst the logs. Most kids would have been, well ya’ know … petrified.

December 8, 2013 12:38 am

Bruce, Always its a pleasure to read your blog. Plese keep going.

Un abrazo desde la Araucanía.

Sergio Pérez

Malalcahuello, Chile, South América.

March 3, 2017 6:54 pm

Hi Thanks for your webpage. Would it be possible to get permission to use one of the photos of Muir at Petrified Forest? I am finalizing an article on the history of paleontology in the National Park Service and looking for a photo of Muir at the petrified forest. Thanks, Vince Santucci, National Park Service

May 5, 2020 3:35 pm

So well written–and exciting! I love the picture of you and Anya exploring together. What a great relationship to have. It is so fantastic to have a like mind to adventure with into the mysteries of the world. Robert Graysmith

June 15, 2021 5:26 pm

Bruce, In your visit, did you see any of the archeological sites at Petrified Forest? According to one website, John Muir was the first to excavate the Puerco Pueblo in the national park: https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM14DT_Puerco_Ruin_and_Petroglyphs_Arizona

see

https://www.nps.gov/pefo/learn/historyculture/puerco-pueblo.htm

Also, he studied the petroglyphs there, and discovered ancient pottery, and one he gave to Alice Cotton Fletcher is now part of the museum collections at the John Muir National Historic Site.

See “John Muir in Arizona, 1905-1906” by Peter Wild at https://johnmuir.org/arizona/

We don’t usually think of Muir as an archeologist, but he had a fascination and appreciation of Native American cultures (a fact misunderstood by many today.)