April 2016. In trying to figure out how John Muir finally found his way to the slopes of Volcán Tolhuaca in November of 1911 to camp under his “long-sought for” Araucarias, our research soon led us to the name of Federico Albert. Albert could be described as the “John Muir of Chile” – although it is more complicated than that, as I will explain later. The two never met when Muir passed through Santiago in 1911, and we are still trying to figure out why – we think it was a narrow miss. Muir apparently did not know that Albert had been instrumental in creating the first protected area in Chile, the Malleco Forest Reserve, even though the site where he camped and sketched was just on its southern edge. The two would have had much in common.

Federico Albert Faupp is considered the father of environmental conservation in Chile (Faupp, his mother’s maiden name, is often retained in Chile, as is the custom with Spanish surnames). He was born in Berlin, Germany, in 1867, studied biology in Berlin and Munich, and by the age of 20 had a doctorate in natural sciences and worked at the Botanical Museum in Berlin. Because of his experience and youth, Albert was offered a job as a professor and preparator at the national Museum of Natural History by the president of Chile, and arrived in Santiago in 1889. For ten years he collaborated with Rodolfo Amando Phillipi, director of the Natural History Museum and a foundational figure in biological studies in Chile – and like Albert, a German, who emigrated to Chile a generation earlier. The natural wonders of Chile seemed to delight Albert, and he became a tireless scientific collector and explorer, travelling throughout the country. On his trips as far south as Chiloé, and Llanquihue in the Los Lagos Region, he became familiar with Chile’s temperate rainforests and Araucaria forests.

Albert’s career shifted in a more applied and influential direction in 1898, when he was put in charge of zoological and botanical studies in the Ministry of Industry. He immediately began a reconnaissance of the central coast, where sand dunes were invading former agricultural lands in many places. In 1900 he visited Chanco, on the coast about 125 kilometers north of Concepción, where an enormous moving front of sand dunes was about to bury the town and surrounding farms. Albert developed a plan to construct a forest that would stabilize and stop the dunes. With the help of the townspeople, he directed a patient effort to plant trees and nitrogen-fixing shrubs. It worked, and that success gained him considerable notoriety and political support.

But his experience in Chanco led Albert to shift his efforts toward addressing the causes of Chile’s environmental problems rather than just reacting to the consequences. He believed that the cancer of the dunes was caused by uncontrolled deforestation, poor agricultural practices, and overgrazing in the watersheds of the rivers that were dumping their unnatural loads of sediment into the ocean, and he knew that controlling those causes would take new laws and institutions, not just tree planting. He therefore initiated an intense campaign for the creation of a government office aimed at the conservation and management of forests and other natural resources. In 1911, the year of Muir’s visit, the Section of Zoological and Botanical Research in the Ministry of Industry, which Albert had directed, finally became the Office of the Inspector General of Forests, Fish, and Game, an agency with a regulatory and management role.

In 1906 Albert accompanied what one Chilean source calls “a forestry mission of North Americans that studied the forms of exploitation of the temperate rainforests of southern Chile.” The group was dismayed, and Albert warned that forest fires, logging on steep slopes, and other unsustainable forestry practices would lead to the extinction of many species within 80 years if not controlled. In 1907, through Albert’s efforts, the first national forest reserve in Chile, the Malleco Forest Reserve on the slopes of Volcán Tolhuaca, was created. It was the first protected area in Chile, and is said to be the first protected area in all of Latin America.

——-

Muir arrived in Santiago by train on November 11th, 1911, and wrote:

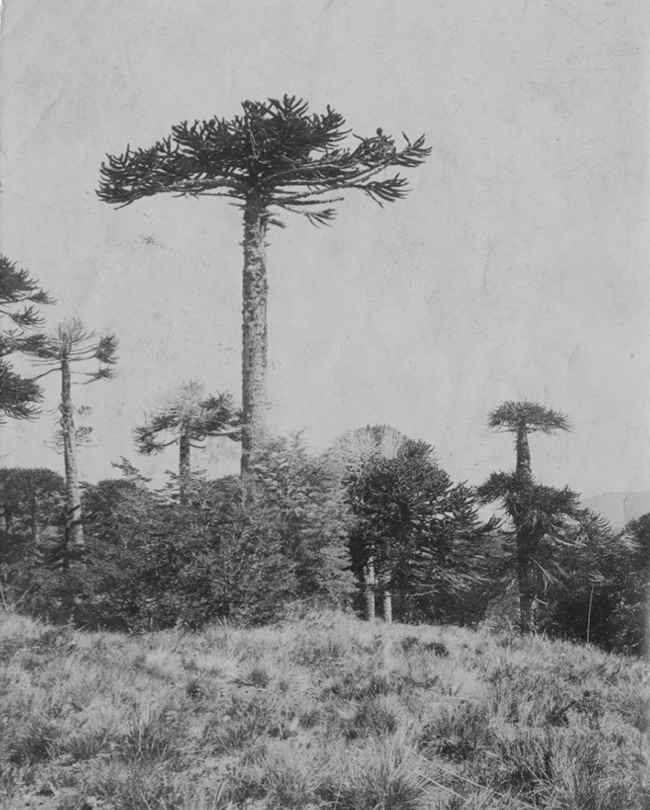

“From the railway station I took a cab to the Hotel Oddo, engaged a room, had luncheon, and drove to the American Legation. On the strength of my credentials from President Taft I was cordially received by Mr. Fletcher, Minister Plenipotentiary from the US, who, to my surprise, invited me to take a room in his house, directed his auto driver, who speaks English, to get my baggage from the hotel and take me to the Botanical Gardens to search for information concerning Araucaria imbricata. The Director of the Gardens took pains to give me a general description of its distribution so far as known. He also presented me with a fine photograph of old trees, which he said must have come from somewhere near Conception, but he had never seen any of the trees of this species growing naturally, and of course could give me no definite information as to how to reach them.”

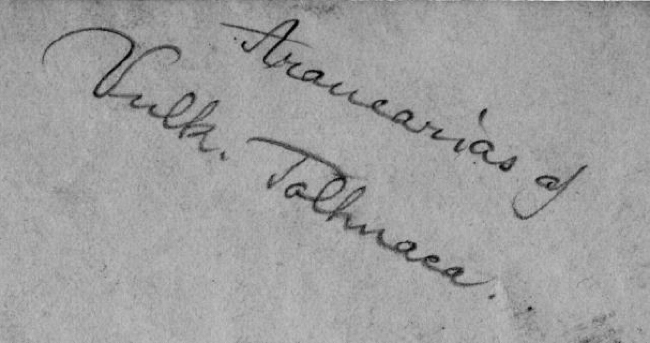

Before we had reconstructed his route to what we now call the “Muir site,” where he finally saw his long-dreamed-of monkey puzzle trees, we were searching for clues, and went looking for this photograph he described in his journal. It was not in the John Muir Papers where most of his journals, letters, photos, and books are now kept, but when we contacted the John Muir National Historic Site, it turned out that they had the photo. The archivist there told us that there was a caption on the back of the photo, and sent us digital images of both the photo and the caption. Our interest was piqued by the caption, which in very clear handwriting said: “Araucarias of Vulk. Tolhuaca.” The mention of Tolhuaca already made sense to us – we knew that where Muir had gone, east of Victoria, Chile, was directly toward Volcán Tolhuaca, in what is now the Tolhuaca National Park. The “of” suggests that the caption was written by, or perhaps for, an English-speaker. But a volcano, or “volcán” in Spanish, is “Vulkan” in German, abbreviated “Vulk.” We immediately suspected that Federico Albert had something to do with this photograph that eventually was given to Muir, and which may have given him the clue that led him to the slopes of Volcán Tolhuaca where he finally saw Araucarias.

Photo of Araurcarias given to Muir at the Botanical Gardens in Santiago in November, 1911. Image courtesy of John Muir National Historic Site, JOMU 3335

Caption on the back of the photo of Araucarias given to Muir at the Botanical Gardens in Santiago in November, 1911.

——-

Our fascination with the entangled history of Federico Albert and John Muir led us on a quest to visit the protected area created in Albert’s honor, the Reserva National Federico Albert, in Chanco. We drove north from Buchupureo, a town north of Concepción famous for its surfing scene, where we had spent the night. The coastal road north passed through extensive commercial forestry plantations of Eucalyptus and pine, and a few quiet, decrepit towns that apparently are jammed with vacationers in summer. Chanco was a bustling little town, the streets clogged with cars and morning shoppers. We eventually found our way to the small visitor center and entrance gate of the reserve.

We drove in to the deserted campground on a sand road with big puddles from the recent rain, and hiked from there on the “Sendero de las Dunas,” a trail that winds out through this non-native forest of huge eucalypts, pines, and cypresses to an area where Albert first began the work to stabilize the dunes in 1900.

At Chanco, Albert carried out an early experiment in what is now called “ecological engineering.” He assembled a simple ecosystem of non-native trees and plants from around the world that could thrive in the sand and the climate of Chanco, and developed a silvicultural system to get them going here. A diorama in the visitor center depicts Albert himself, with hoe in hand, heroically laboring to plant barriers of European beach grass, Ammophila arenaria, and Spanish broom, Genista hispanica, to stop the dunes. Both species are still thriving today. Spanish broom, native to SW Europe, is a leguminous shrub that fixes nitrogen in the soil, as Albert knew. In the engineered forest we saw Acacia melanoxylon, Australian blackwood, native to southeastern Australia; Pinus radiata, Monterey pine, from California; and Eucalyptus globulus, Tasmanian bluegum, from southern Australia. Some of these species are now naturalized, reproducing on their own without further human intervention.

The term “ecological engineering” was coined by systems ecologist Howard T. Odum in 1962, who described it as an ecological intervention where “… the energy supplied by man is small relative to the natural sources but sufficient to produce large effects in the resulting patterns and processes.” The townspeople of Chanco, guided by Albert, certainly worked hard planting trees, shrubs, and grasses, and their efforts did result in ecological patterns and processes that eventually defeated the wind and sand.

I saw this as a fascinating experiment in creating an “artificial” ecosystem. Ecologists talk about how in this era of invasive species and climate change, novel assemblages of plants and animals that have never existed before may soon come into being. Federico Albert’s constructed forest ecosystem is an experiment and example that could be studied, and there is lots of research to do. How many native species have moved in over the century or so since it was constructed from non-native species? How resistant is it to non-native invasive species? How resilient is it now to climate variability, and what about in the future of climate change? In native forests with an eco-evolutionary history of eons, the plants have co-evolved suites of insects, birds, mammals: what about here – have novel co-evolutionary relationships developed?

According to one website, “very slowly, with time, native species have appeared, such as boldo (Peumus boldus), peumo (Cryptocarya alba), corcolén (Azara celastrina), maqui (Aristotelia chilensis), maitén (Maytenus boaria), and litre (Lithraea caustica). What about animals? We saw a few birds, of only four species – not a lot compared to native natural ecosystems. Information on the web lists almost 20 bird species found in the reserve. As far as mammals go the reserve supports a handful of species, including the South American grey fox (Lycalopex griseus) and culpeo, or Andean fox (Lycalopex culpaeus), but not Darwin’s fox. It seems that in terms of species diversity, Federico Albert’s engineered forest is still a depauperate ecosystem.

——-

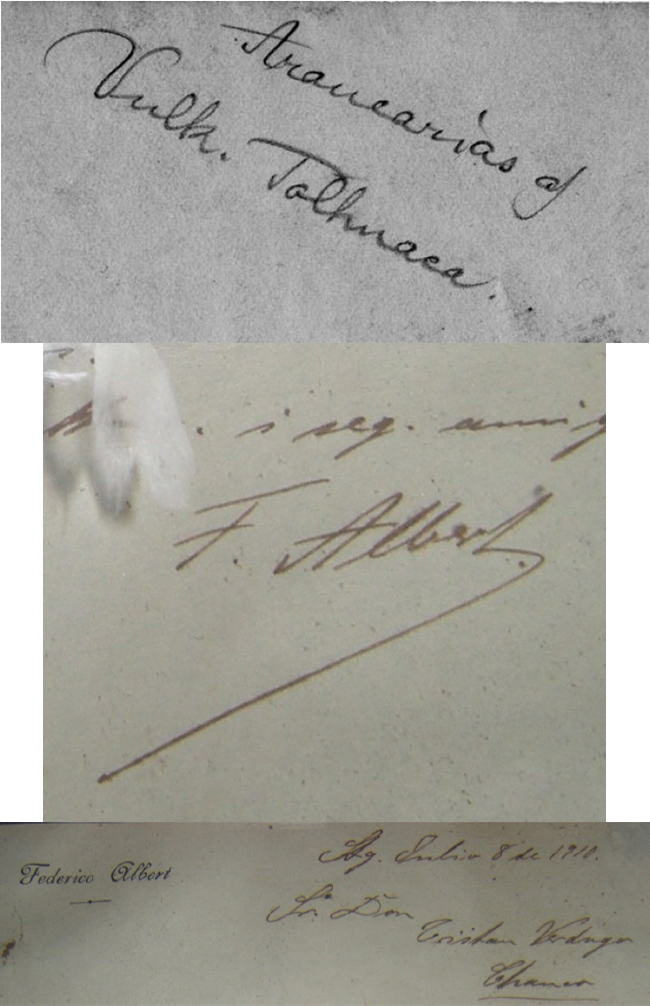

Our visit to the Federico Albert National Reserve in Chanco finally gave us further evidence that the photo of “Araucarias of Vulk. Tolhuaca” that was given to Muir was originally from Federico Albert. In the visitor center at the reserve a copy of a handwritten letter from Albert, dated the 8th of July, 1911, was displayed, which greeted and sent best wishes to a Don Cristan Verdago (the name is a little hard to make out) and the townspeople of Chanco. Like forensic sleuths, we analyzed the “A”s and “V”s and “T”s in the letter, comparing them with the caption on the photo, and were convinced: Federico Albert wrote the caption on the back of the photo given to Muir. The “A” in “Albert” and “Araucaria” are distinctive, and match perfectly, for example. The photo was probably taken on Albert’s 1906 forest reconnaissance trip.

Handwriting comparison of caption of photo given to Muir with letter from Albert to his contact in Chanco

——–

In 1912, the year after Muir’s visit, Albert wrote: “Where are we going? It is now fitting to ask whether after so much destruction, without limits, of the riches of our forests, fish, and wildlife, we see this as the worst enemy of our country, and whether there remains enough to even maintain our most indispensable industries.”

This may be interpreted as a utilitarian argument for nature conservation, and Albert sounds quite a bit like George Perkins Marsh, whose 1864 book Man and Nature was an early exploration of ecological ideas and a plea for conservation in the United States. Marsh wrote that “the operation of causes set in action by man has brought the face of the earth to a desolation almost as complete as that of the moon.” He argued that human welfare required the management of nature to maintain its benefits to society. Marsh’s work strongly influenced Gifford Pinchot, the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service, which was created in 1905. Pinchot is often described as a utilitarian conservationist.

But it is interesting to compare Albert’s words and views with those of John Muir, who some have interpreted as promoting nature protection for only non-utilitarian reasons – an interpretation that oversimplifies Muir’s views. For example, in an article that argued for the creation of a system of national forest reserves in the United States titled “A Plan to Save the Forests,” published in Century Magazine in 1895, Muir wrote: “It is impossible… to stop at preservation. The forests must be, and will be, not only preserved, but used. Forests, like perennial fountains, may be made to yield a sure harvest of timber, while at the same time all their far-reaching beneficent uses may be maintained unimpaired.” His progressive, pragmatic view was a balance between sustainable use and long-term protection.

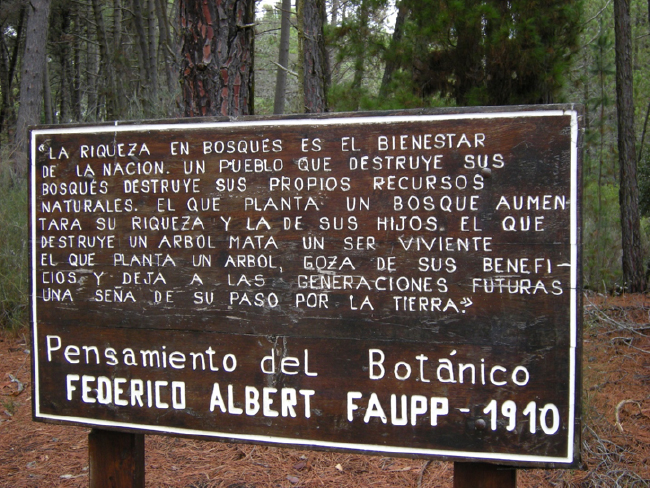

In 1910 Albert wrote: “The wealth of forests is the well-being of the nation. A people that destroys their forests destroys their own natural resources. He who plants a forest increases his wealth, and that of his children. He who destroys a tree kills a living being. He who plants a tree enjoys its benefits and leaves for future generations a sign of his passing through the land.” As I said at the beginning, Albert is too complicated to be only the “John Muir of Chile;” he is the “Gifford Pinchot of Chile” too. To me, his perspective sounds like a hybrid between Muir and Pinchot.

It’s too bad John Muir didn’t meet Federico Albert. They would have had a lot to talk, and maybe to argue, about. Their ideas about the human-nature relationship, and their legacies in building a system of nature conservation, live on in both Chile and the United States.

For related stories see:

- Tracking John Muir to the Monkey Puzzle Forests of Chile

- Following Muir’s Route in Sketches and Photos

- Documenting Forest Change at the Muir Site

- Maples, Mapuches, and Monkey Puzzles: Human Dimensions of John Muir’s Travels in Chile

- All I Came to Seek I’ve Found: Closing the Loop with John Muir in California

- The View from El Cañi

- Following Up on Following John Muir to the Monkey Puzzle Forests of Chile

- John Muir Slept Here, and the Mystery of the Missing Monkey Puzzle Pictures

- Camping with Darwin’s Fox: Nahuelbuta National Park, Chile

- Lunch at Grey Towers

Sources and related links:

- Federico Albert (1867-1928)

- Federico Albert Faupp: 1867-1928.El primer conservacionista de la naturaleza chilena.

- Federico Albert Faupp

- Rodolfo Amando Philippi

- Rodulfo Amando Philippi (1808-1904)

- Reserva Nacional Federico Albert

- Reserva Nacional Federico Albert – El Eucalipto

- What is “ecological engineering”?

- Man and Nature: Or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. 1864. George Perkins Marsh.

June 17, 2016 2:21 pm

Bruce,

Perhaps the most fascinating of all your essays. Too many environmentalists show photos of a successful ecological engineered situation using non-natives without asking the ecological questions that you have. It is a fascinating opportunity to look at the long-term implications of a successful ecologically engineered intervention.

I wonder … It seems unlikely (to me) that rapid dune shifting was normal in this ecosystem. I’m guessing that small-ruminant grazing (due to the villagers themselves) reduced the vegetative cover that once stabilized the dunes (which is the case in much of the Sahel and China’s loess areas). To me, it looks like Albert came to the rescue at the last moment to install a system that goats couldn’t destroy (even then, he must have imposed a moratorium on grazing for awhile).

Rich

June 20, 2016 2:09 pm

Rich,

I’m glad if you enjoyed this story, and thanks for the feedback!

I think you must be right – there were probably some local causes of the moving dunes at Chanco, probably both farming and grazing that disrupted the native coastal ecosystem. We probed the staff at the Reserva Nacional Federico Albert about that, asking, “Well, what kind of vegetation was here BEFORE people started farming at Chanco?” They hadn’t even considered the question, and had no idea – they seemed to be able to imagine only back to the sand at the turn of the nineteenth century, not earlier. A lot of information does seem to suggest non-local causes as well, however – deforestation and poor agricultural practices in inland watersheds – which is what finally motivated Albert to take a larger view of the problem.

I discuss a “home-grown” case of a possibly parallel example in my story “Pondering the Palms of Cape Hatteras,” from November 2015. Gifford Pinchot, as a private forestry consultant, surveyed North Carolina forests for the North Carolina Geological Survey in 1897. His report was the first to characterize the maritime forests of the Outer Banks, and he reported that timber cutting had mobilized sand dunes, which were engulfing communities and the forests themselves. “Some such areas were originally forest-covered,” he wrote, “but once cleared… the constant movement of the sand before the winds, which have piled it into shifting dunes, has prevented a general growth of any kind from securing a foothold.” Turns out that was probably too simplistic an explanation, but he was partly right.

Bruce

June 19, 2016 10:39 pm

Another interesting travel log.Good work.

—Sid