January 2016. In my mind mahogany is one of nature’s wonders, one of the most beautiful woods in the world. Maybe that’s because my dad decided to use mahogany paneling in my bedroom when he was building the house where I grew up. It wasn’t veneer, either. That was back in the day when, I’m sure, Guatemalan forests were being pillaged for mahogany to make such then cheap, but beautiful, wood products. And so I slept surrounded by the warm rich brown of mahogany until I left home for college. Because of that history, I felt a personal interest in seeing how rural communities in Petén are trying to implement a sustainable harvesting system for mahogany and other high-value timber species in the lowland forests of northeastern Guatemala, on the border with Belize.

My alarm went off in the dark in my room at Casazul Hotel in Flores. It was still dark when we picked up Don Jorge, the ACOFOP community concessions coordinator, who was going with us for the day, at 6 AM. ACOFOP is the Asociación de Comunidades Forestales de Petén, a support organization for the 23 communities with community forestry concessions in the multiple-use zone of the Maya Biosphere Reserve.

We stopped for gas at a brightly-lit Texaco station on the highway going east out of town, and then watched as the red and pink band of the coming sunrise painted the horizon ahead. I remembered those colors, watching another sunrise from the top of the Temple IV at Tikal in 2014. We were passing just south of Tikal on this road from Flores. As we drove we encountered patches of fog, spilling over the hills and ridges, and I wondered if they would see the sunrise from Tikal today. The dawnlight was rich and beautiful, and calming, now with a salmon-colored fog hanging in the valleys. Finally we drove up and over a ridge, not really so high, and the fog was suddenly gone. Don Jorge, who had been telling us the names of all of the little clusters of houses along the road, announced that this place was Puerta del Cielo, the “Door of Heaven.” Perfect name, I thought. Below us to the east was a sea of clouds, with hilltops poking out here and there. We soon dropped down into the fog layer again.

At around 8 AM we reached Melchor de Mencos, the main town on the frontier with Belize. Don Jorge directed us to a tiny, chaotic market plaza, where we parked and went into the Comedor Las Delicias. Ah! Huevos rancheros : two crispy-fried eggs, black beans, crema acida, white cheese, and tortillas of course. It tasted delicious. The coffee was powdered Nescafé.

After breakfast we turned north in the sunshine as the disorganized, colorful chaos of the day was just getting going. Roosters in the road, mothers taking their kids to school, tuc-tucs and motos, a pickup with a cow in the back, dilapidated sidewalks, bumpy cobbled roads, brightly painted buildings. A bit like Africa in a way, this energetic disarray makes the order and predictability of home feel a bit boring.

We stopped at the office of the Sociedad Civil “El Esfuerzo” to learn about their efforts – esfuerzo means “effort” in Spanish – to bring economic benefits to their local community from the sustainable management of mahogany and other high-value timber species. El Esfuerzo manages one of the community forestry concessions located in the Maya Biosphere Reserve. As I explained in a recent story, “More Ecological Musings from the Maya Forest,” the Maya Biosphere Reserve was established under the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Program in 1990 to protect the largest area of tropical forest remaining in Central America. The total area of the reserve is around 22,000 square kilometers. A buffer zone of around 5,000 square kilometers, or 24% of the total area, spans the southern side; 36% of the reserve is a core zone, consisting of national parks and nature reserves; and multiple-use zones of around 8,500 square kilometers make up the remainder. Today we would be passing through the buffer zone and into the multiple-use zone where the El Esfuerzo community concession is located.

We talked with the director for about ten minutes, and then headed north again, taking two El Esfuerzo staff as our guides for the day: Roberto, a forester, and Sergio, the treasurer of the organization. The road was rough dirt, not even graveled, and in this limestone landscape there were a lot of rocks, and some muddy patches. We were driving through the zona de amortiguamiento, the buffer zone, of the biosphere reserve, which here, north of Melchor, is about 20 kilometers wide. The road passed through large cattle ranches, with some patches of forest on the hilltops and ridges. In about 45 minutes we drove through a huge commercial maize farm that looked like Iowa – this clearly was not the subsistence farming that is all that is supposedly allowed in the buffer zone – and came to a green wall of tall trees that marked the boundary between the buffer zone and the multiple-use zone of the biosphere reserve. The contrast in vegetation was stark. This boundary was as “hard” as any protected area boundary I’d seen anywhere in the world.

Just inside the forest, maybe 100 meters, was the control post, where a ranger from CONAP checked our credentials to enter the reserve. CONAP is the Consejo Nacional de Areas Protegidas, or National Council for Protected Areas, responsible for managing the biosphere reserves, national parks, and other protected areas of Guatemala. An armed soldier from the Guatemalan army stood at his shoulder. While we were waiting for the paperwork to be completed I walked up the road a short distance. It was dark, moist, and cool under the forest canopy, a stark contrast to the bright sun of the buffer zone ranches and maize fields. I heard the morning roaring of howler monkeys, not far away.

We drove north, paralleling the border with Belize, which was only three or four kilometers to the east here. We passed a junction where a road as bad as the one we were on turned east, toward El Pilar, a Mayan ruin spanning the border of Guatemala and Belize. In about an hour we came to a clearing – a zona de acopiliación, or collection point – where a 2014 timber harvest by the El Esfuerzo concession had pulled in the harvested trees on a spoke-like network of skidder trails and loaded them onto trucks. This was the objective of our long drive, the place where we could get a tutorial on sustainable forest management in community concessions.

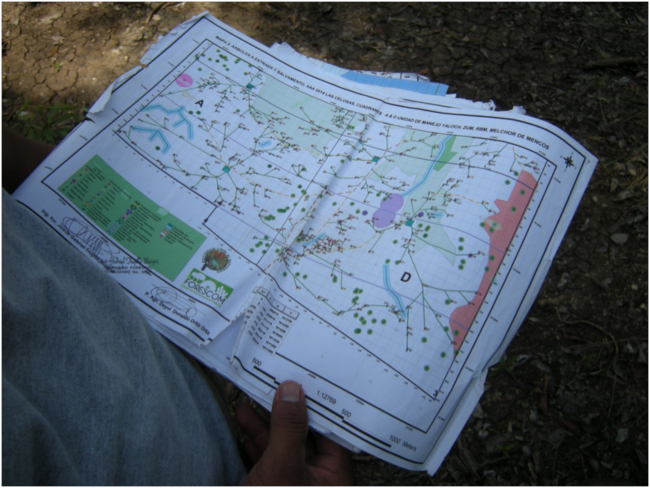

As soon as we stepped out of our truck we noticed that in this area, which had been cleared and the soil exposed by log-loading operations, was thick with baby mahogany seedlings, some a meter tall. Roberto, the forester, pulled out the map of this location from the overall forest management plan for the El Esfuerzo concession. The skidder trails from this collection point were mapped, and we followed one of them out to the site of a mahogany tree that had been harvested in the 2014 cut, labelled “D52.” The trails where logs had been dragged and bare soil exposed were now thick with young trees and shrubs. With a GPS unit to confirm it, we found the stump of D52, a caoba (the local name for mahogany). Tropical trees, often growing on thin soils, often develop thin, fin-like buttresses at ground level to stabilize them. D52 had been a mahogany with three buttresses, and a trunk diameter inside the buttresses of about 18 inches. Although not really a very big tree, Sergio, the El Esfuerzo treasurer, estimated that the wood from D52 might have been sold for around $2,000 US dollars, which is a lot of money in rural Guatemala.

ACOFOP community concessions coordinator Jorge Soza explaining how mahogany is measured to determine the growth rate for management planning

I was completely fascinated to be on the ground, for my first time ever, in a certified, sustainably-managed tropical forest with a forester who had crafted the management plan. I have been so skeptical in other cases where I’ve read secondhand reports about supposedly-sustainable forest management, and I was looking for problems. I asked Roberto all the probing questions I could think of, but he could answer them all. The plot-by-plot mapping of high-value species they have done – and he showed me the species-by-species tree census of this plot we were walking in – is what is needed to develop a plan for a sustainable cut of those species within their community concession. Setting sustainable quotas for harvesting trees is similar to, but different than, the science of setting sustainable quotas in fisheries. Trees don’t move, but grow and reproduce. Fish move, grow, and reproduce. The ecological understanding needed to underpin sustainable management is complicated in both cases, in different ways.

Map showing locations of mahogany and other high-value timber trees from the El Esfuerzo concession forest management plan

In their management plan El Esfuerzo is mainly going after mahogany, and another related high-value species, cedro, or Spanish cedar, although they also harvest a dozen other timber species, as well as xate, a species of palm found in the shady forest understory that is used in the international floral industry.

After exploring the skidder trails radiating out from the log collection site, we crossed the road and walked about 50 meters through the deep selva to the east to see a big, straight-trunked mahogany that had been designated as an arbol de semillas, a seed tree, to be left and never cut in order to provide the seeds for natural regeneration. Don Jorge explained the criteria for selecting seed trees: clean, straight, and with a crown in the canopy. This one was undoubtedly the mother of the baby trees we saw in the former log loading area.

Mahogany, scientific name Swietenia macrophylla, or caoba in Spanish, is sometimes called big-leaf mahogany to distinguish it from a couple of related species. Its seeds are winged, dehiscing from pods when mature, and can fly long distances like maple, spruce, pine, or other winged, wind-dispersed seeds. Writing about the natural history of mahogany in A Natural History of Belize: Inside the Maya Forest, Samuel Bridgewater summarized the conditions that favor mahogany reproduction, which we were observing here: “Occurring as a tall tree in mature forest, mahogany is a light-demanding species, and moderate disturbance is ideal for its development. Indeed, light hurricane damage or fire can provide ideal conditions for mahogany regeneration, with mature trees withstanding damage better than many other species. The fast-growing seedlings are also well adapted to exploit canopy gaps caused by treefall.”

Along the road we saw another example of enthusiastic mahogany reproduction created by a combination of a mature seed tree and bare, disturbed soil. We stopped where thick forest of young mahogany was growing right along the road. The roadside had been graded bare about ten years ago, and a big mahogany that we could see towering on the east side of the road had seeded it. The El Esfuerzo foresters were using this young roadside forest as an experimental plot. They had individually marked and were measuring the diameters of the trees in to get better data on mahogany growth rates in the area, information that would help them refine their management plan.

In the early afternoon we drove south again, and passed out of the cool, tall, rich selva, into the sad sunny pastures of the buffer zone with its cattle ranches. Having seen the native forest, I could now really feel what had been lost. This time I noticed the names of the fincas, posted on the gates along the road. Many names were inspirational: Finca Nueva Amanecer. Finca La Esperanza. New Dawn Ranch. Hope Ranch. But these were obviously rich peoples’ ranches – I would be a lot more sympathetic if the forest had been cleared by poor campesinos struggling to feed their families. Roberto and Sergio said this was an area of narco-ganaderia, where drug money was being laundered through land purchases and cattle ranching. Don Jorge chimed in to say that the #1 threat to forests in Petén was this kind of drug-lord ranching.

We passed through Melchor de Mencos, dropped our guides Roberto and Sergio at the El Esfuerzo office, and stopped quickly for a late lunch of fast food, fried chicken and french fries, at a local joint, Pollo a la Prisa or something like that. Then back westward toward Flores, passing again through the Door of Heaven. In a little town called Ixlú we stopped to visit a community forest-based enterprise, Alimentos NutriNaturales, run by an entrepreneurial cooperative of women. These local ladies harvest, process, and sell various products made from the fruits of a tree called ramón, gathered in the forests of the Maya Biosphere Reserve. Ramón, whose scientific name is Brosimum alicastrum, is a member of the fig family. Its fruits are round, about the size of grapes, and with a brown husk. When dried they can be ground into a flour, which can then be mixed with water to make a beverage something like hot chocolate, or baked into cookies. Ramón has a sweet, nutty, unique flavor.

One of the Guatemalan conservation experts we interviewed made a statement that really stuck in my head. Talking about the challenges of stopping narco-ganaderia, he said “No puede frenar la narco-ganaderia con galletas de ramón.”: “You can’t stop narco-ranching with ramón cookies.”

Well, he is probably right. In our assessment interviews with a wide range of Guatemalan experts on biodiversity and forest conservation we had already heard their collective opinion that what is needed to protect the environment in Petén is for the Guatemalan government to regain control of this part of the country. They suggested that the government should use the army, police, and judicial system to stop illegal land conversion like narco-ganaderia and other illegal activities.

But, on the other hand, I had an immediate sympathy for these ramón-harvesting women. The Guatemalan experts we interviewed provided a long list of actions needed to conserve forests and biodiversity in Guatemala, and there were other themes besides stopping illegal forest conversion. Another main need was, they told us, to support community organization, empowerment, and capacity – such as in the community forest concessions like El Esfuerzo, or the women’s ramón cooperative in Ixlú. In both cases, we also saw examples of how providing economic options for poor rural people who depend on natural resources from forests can support development while conserving biodiversity, another key need identified by the people we interviewed.

Although I am often a skeptic when it comes to believing that people can figure out how to sustainably manage natural resources, I’m also somehow a congenital optimist. What I saw in the El Esfuerzo concession gave me hope that mahogany can survive to enrich future generations with the beauty of its wood. And the galletas de ramón ? ¡Deliciosa !

For related stories see:

- More Ecological Musings in the Maya Forest. January 2016.

- Sugar Maples, Ecohydrology, and Climate Change in the Sierra de las Minas of Guatemala. February 2016.

- Quetzal and Coffee at Los Tarrales, Guatemala. January 2016.

- Ecological Musings in the Maya Forest. March 2014.

- Screeching Macaw, Hidden Jaguar. March 2014.

Sources and related links:

- Asociación de Comunidades Forestales de Petén

- Guatemala Tropical Forests and Biodiversity Assessment Draft Report March 2016

- Maya Biosphere Reserve

- Swietenia macrophylla, big-leaf mahogany

- A Natural History of Belize: Inside the Maya Forest. 2012. Samuel Bridgewater.

- Ramón, Brosimum alicastrum

- Alimentos NutriNaturales, Guatemala. UNDP Equator Initiative Case Study.

October 13, 2016 7:04 pm

1. I read your posting with great interest. I think there is good potential for community management of humid forests in Africa but very little has been done. Cameroon is the most advanced but results seem to be very unimpressive. GIZ has just started a pilot in DRC. Beyond that I don’t know of any attempts to do this in Africa in humid forests.

2. What is the legal status of Sociedad Civil “El Esfuerzo”– what type of organization is it?

3. “Buffer zone” is a term that is used to mean many different things. What is its legal meaning in this case?

4. The term concessions is most commonly used for blocks of forest that are awarded to industrial logging companies for a fixed period of time. In my experience, the term is not commonly used for community-based forest management – at least in Africa. What does concession mean is this context and how does it differ from an industrial logging concession? Most importantly, is there any guarantee that the community’s concession will be renewed for the community managers when its term is up if they have managed it well?

5. I just learned with a search engine that the first species of tropical tree to be called mahogany and that was adopted very early by major furniture makers of Europe was the Cuban mahogany (Swietenia mohogani) S. macrophylla became its first replacement after the Cuban mahogany was harvested to commercial extinction by the mid-1980s (http://www.woodmagazine.com/materials-guide/lumber/mahogany). Mahogany is a term that is used very loosely in world markets. When I was an undergrad in the late ‘60s, there were about 70 species marketed under the name of “mahogany”.

6. It is probably relatively easy to manage for light-loving pioneer species like Swietenia macrophylla. – okoume (Aucoumea klaineana) in the Congo Basin also has abundant regeneration following logging/disturbance. But we found (from research organized by WCS) on an assessment I led of the largest logging concession in northern Republic of Congo in 1995 that there was no regeneration at all, in commercial terms, of the two species of African mahogany (Entandophragma cylindricum and E. utile) that made up close to 90% of their harvest at that time. Some of the trees were 900 years old and harvesting them seems to have been more like a mining operation on that site.

7. Given that Swietenia regenerates so abundantly after logging, is there not a danger that the forest will become dominated by Swietenia over time and that much of the biodiversity will be lost? Coastal okoume stands that I have seen in the Republic of Congo that have been repeatedly logged over are strongly dominated by this okoume.

8. I believe there is great potential for developing intensive community humid forest management in charcoal supply zones of urban centers. One could do frequent, light selective thinnings on areas already cut over harvesting low value trees for wood fuels and preserving trees of high commercial and conservation value for later harvest or as seed trees. One could sequester a lot of carbon in this way.

9. Certification may be no panacea. The head of FSC in Brazzaville told me in July that the company with the largest area of certified humid forest in Gabon and Republic of Congo intends to ultimately convert their concessions into cocoa – and that this is supported by government policy in Gabon. Governments that have been funded by oil revenues are desperate for alternative sources of income.

October 16, 2016 8:01 am

Roy, thanks for your interest in this story, and your thoughtful questions and comments.

In Guatemala at least, the community-managed forest areas within the multiple-use zone of the Maya Biosphere Reserve are called “community concessions.” They are mostly managed for high-value timber like mahogany, but many are also trying to maximize the overall revenue from their area by harvesting non-wood forest products like ramon and xate.

Your question about whether mahogany might become more common after a long period of selective cutting in the Maya Forest because of its successful reproduction following disturbance is an interesting one. The comparison with okoume in the Congo Basin is fascinating! During the Classic Mayan period, the whole region was dramatically more disturbed and deforested than today. Maybe that stimulated an anthropogenic shift in forest composition favoring mahogany that was then exploited by loggers starting in the 1800s? That would make an interesting study in historical ecology!

You raise so many interesting questions, most yet without clear answers, I think. In our assessment report, one of the four main opportunities we recommended that USAID address was the need to generate information to catalyze change in environmental management in Guatemala. Your questions reinforce that idea.

October 16, 2016 8:12 am

For my friend and professional colleague Luis Caballero, an ecohydrologist with whom I worked in Honduras (see my blog “Ecohydrology of the Honduran Highlands” posted in October 2013) this story triggered a childhood memory. With his permission, I share his response below:

Dear Bruce,

Glad to read your nice report of your trip to Guatemala. As I read through, I saw the picture of the ramon fruits, and immediately it came to my mind, I know this fruit, it is called masica in Honduras. When I was a kid, my brothers and I collected them from the forest, brought them home, and cooked them in water with wood ashes, then we peeled off the skins and ate them. It provided a good source of energy to go out play soccer and other traditional games. Masica had a special place in our childhood life, as we frequently visited forests and rivers and harvested whatever was edible.

Saludos my friend, good to hear these well written stories from you.

Luis

September 8, 2021 8:15 am

Dear Bruce,

Wonderful article. Do you ever

travel to the Philippines?

If so, please give us a heads up so you can visit us in Mindoro.

Regards,

Joseph