Forested ridges rolled away in the early morning light as far as the eye could see from the top of Canaa, Sky Place Temple, at the ancient Mayan ruins of Caracol. Howler monkeys were still roaring from the tall trees below this artificial mountain that rises above the Maya Forest. We took our leave of the view and descended, and after a hearty breakfast back at the research camp we drove north, crossing the Guacamallo River. Our plan for the day was to try to see scarlet macaws in their prime nesting habitat along the Macal River, in an area that was partially flooded by the reservoir of the Chalillo Dam in 2008. The road climbed up and then turned back to the east, crossing part of the Mountain Pine Ridge Forest Reserve. The granite substrate here creates the habitat for pines, which are adapted to poor soils and frequent fires. It was a much different ecosystem than the lush, broadleaf forest surrounding Caracol. From a high ridge we dropped into the valley of the Macal, and soon saw the dam and reservoir behind it.

Just upstream from the dam and hydroelectric powerhouse a steep road dropped down to the shore. Two small boats were already in the water waiting for our group of about a dozen people, mostly U.S. Embassy staff and friends. In our boat was Derric Chan, the manager of the Chiquibul National Park, the largest national park in Belize, whose protected forests rise from the south shore of the reservoir. The park is managed through a co-management agreement between the Belize Forest Department and the non-governmental organization Friends of Conservation and Development. This kind of co-management arrangement is the norm in Belize, and many Central American countries.

The scarlet macaw (Ara macau) is a spectacular red, blue and yellow parrot. Adults are almost three feet long, with about half of that length a long, forked tail. The species is found throughout the Amazon and Orinoco Basins in South America, with a subspecies ranging north through Central America and into tropical Mexico. Globally, scarlet macaws are not under immediate threat of extinction. But an illegal pet trade is the main threat to many populations, combined with habitat loss, and the species is listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which prevents all international trade. In Belize, the species is considered nationally threatened, with a total population estimated at between 125 and 250 individual birds.

From the boats the difference in vegetation on the two sides of the reservoir was striking. On the granite soils of the Mountain Pine Ridge to the north were sparse pines and oaks. To the south, limestone soils supported a lush forest, where we soon started to see tall, branching, pale-barked quamwood trees (Schizolobium parahyba) emerging above the forest canopy. Quamwoods are the favored nesting trees of the scarlet macaw because when big branches break off the trunk, deep cavities can form, creating perfect nest-nurseries for macaw chicks. The Chalillo Dam was extremely controversial when it was proposed and built because it flooded a riverine forest full of quamwoods along the upper Macal River and its tributary the Raspacula.

We learned from Derric, the park manager, that the main threat to scarlet macaws here is the capture of their chicks for the illegal pet trade. This is uniformly blamed on Guatemalans – the border is very close here. A scarlet macaw chick can sell for around 55,000 Quetzales, the Guatemalan currency, on the illegal international market, he said. [Interesting that the Guatemalan currency is named after another spectacular and threatened bird of these forests, the resplendent quetzal.] That is about $7,500 US dollars, or about one and a half times the average annual per capita income in Guatemala. It isn’t hard to see why stealing macaw chicks would be an economic motivation for some Guatemalans, or even Belizeans. Friends of Conservation and Development has started a nest monitoring program, locating macaw nests and visiting them periodically, both to deter poachers and to record nesting progress. They estimate that seven or eight out of every ten nests were being poached until recently. Natural predators – snakes, hawks and owls – kill the chicks in another two of ten nests. It doesn’t take a math wizard to see that with those statistics, macaws are barely making it, with maybe one nest in ten fledging two chicks every year.

We scanned the big trees as we went up the reservoir, and after twenty minutes or so someone spotted a pair of macaws. They are striking once you see them, but the macaws didn’t stand out as much as I had imagined they would; a common epiphytic bromeliad of these forests has red leaves, so there were many patches of red color on the branches of the big quamwoods besides scarlet macaws. After watching the first pair for about twenty minutes we went on, reached the confluence of the Raspacula River, and continued up the righthand fork, the upper Macal. Soon another pair was spotted, this time with a third bird – a “pair and a spare,” we called them. They squawked and moved among the branches while we marveled at their amazing colors. Another half-hour upstream we found a third pair at a nest hole where a big lower branch had broken off. Our guides took us ashore here, purportedly to walk closer to the nest for better views, but also as an excuse to relieve ourselves of our morning coffee after some two hours on the water. Perhaps disturbed by our presence on land, the macaws launched into the air and treated us to a spectacular screeching flight up and then down the river in front of us.

Why conserve scarlet macaws? Because they are a spectacular, unique, charismatic species. Their feeding and nesting territories range over the landscape of Belize, symbolic of the interconnections of the country. [They are the national bird of Honduras – apparently the Hondurans also see this species as symbolic of the unity of their country.]

When not hanging around the Macal River where we saw seven of them, scarlet macaws sometimes head east into the Cockscomb Basin, to an area near the town of Red Bank, in search of their favorite wild fruit trees. That was where we were headed next, but not in search of macaws.

The Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary in southeastern Belize is the world’s first and only protected area dedicated to conservation of the jaguar, the largest cat found in the Americas. The sanctuary was established in 1986, partly because studies by Alan Rabinowitz, working with the Wildlife Conservation Society, showed that this area had the highest density of jaguars in Belize. Now there are an estimated 60-80 jaguars in the 124,000 acres of the sanctuary.

We turned off the Southern Highway between Dangriga and Punta Gorda at the town of Maya Center at 10:30 in the morning, and paid our entry fee at the Maya Women’s Craft Cooperative. At the Wildlife Sanctuary Visitor Center we studied the trail map and conferred with Fred, the Belize Audubon Society staffmember at the information desk. [Here at Cockscomb, the Belize Audubon Society is the co-managing agency, as Friends of Conservation and Development is at Chiquibul National Park.] A preserved fer-de-lance (Bothrops asper), the deadliest snake found in these forests, leered at us from a big jar of formalin on the countertop, it’s eyes turned blue by the preserving process. As we headed up the Tiger Fern Trail in the heat of the day we hoped we wouldn’t see a live one. Our plan was to climb to a viewpoint overlooking the Cockscomb Basin at the top of a ridge, and then descend into a valley with a double waterfall.

The trail passed through lush tropical forest. There were huge tree ferns, giant understory palms, big buttressed ceibas, and a fern-like clubmoss on the forest floor. The trees were overrun with climbing vines and epiphytes – arums, bromeliads, ferns, philodendrons, and what are called “mano de tigre,” “jaguar paws,” in Spanish – several of them very similar to the houseplants in my temperate-zone house.

The climb to the ridge was hot and sweaty, but the effort was finally rewarded with a hazy view north toward Victoria Peak in the Maya Mountains, at 3,675 feet the second highest peak in Belize.

Then came the payback for our sweaty work. We dropped down a steep, rough trail into the next valley, and in half a mile reached a pair of waterfalls. The lower falls dropped about 30 feet into a deep pool, but on a shelf above it was another falls more than twice as high, with its own lovely plunge pool. We scrambled to the higher pool and slipped into the refreshing water, and when cooled enough climbed out onto a sunny rock to dry and warm up again. An alternation of swimming and sunning filled the afternoon. I imagined jaguar eyes watching our every move. Jaguars. Yes, we came to the Cockscomb Basin because of jaguars. We hadn’t seen one, of course, and didn’t really expect to.

Why conserve jaguars? Now that question, for me, is more complicated than the previous one: Why conserve scarlet macaws? One reason for conserving jaguars was alluded to on a billboard near the turn to the Belize Zoo on the Western Highway between Belize City and Belmopan. It said “Protect the Predators, They Maintain the Balance of Nature.” Now, if you ask an ecologist about the “balance of nature,” you are likely to get a complicated and ambiguous answer that you probably won’t understand. The reason is that ecosystems are so complicated that they are sometimes stable and “balanced,” but sometimes very unstable, flipping from one state to another based on factors that are not really well understood. Ecosystems are complex systems, and even ecologists don’t understand everything about them.

Balance of nature or not, however, it is still a fact that top predators – like jaguars, or sharks in the oceans – are generally the rarest of species. That fact is a simple consequence of the way energy flows through ecosystems, with herbivores eating plants, and predators eating herbivores, and huge amounts of energy being lost at each of these food-chain links. The consequence is that jaguars and other predators are rare, sparsely distributed through an ecological landscape. And so, if an ecologist or conservation biologist were to draw up a plan to conserve all of the biological diversity in a landscape, they could with good reason make a case for conserving an area capable of sustainably supporting a population of the top predator – like the jaguar. This idea is the underlying rationale for the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary.

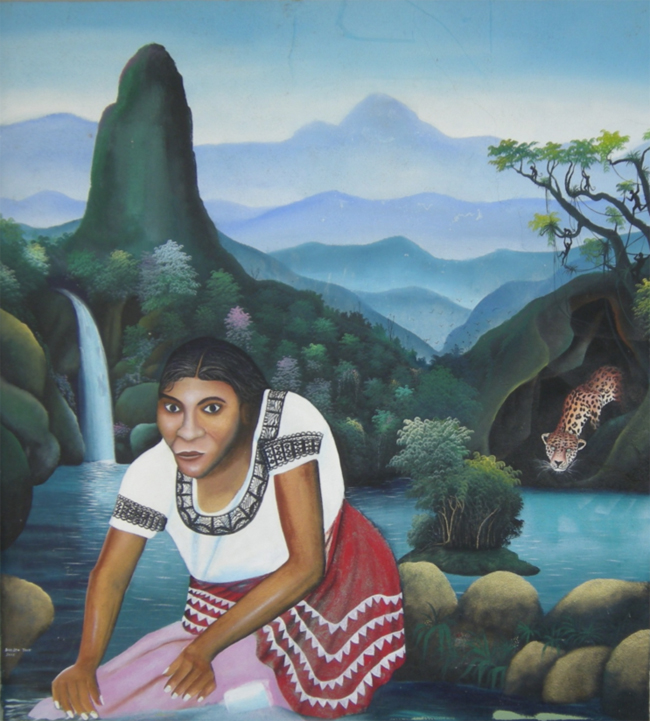

So why conserve jaguars? Beyond the ecological rationale, there is another reason, equally valid; jaguars have a psychological, emotional, spiritual, and cultural value to us humans.

Why? Because we are part jaguar, and they are part of us. The Mayan shamans knew that much better than we do now. At Tikal, Temple III is known as the Temple of the Jaguar Priest because a bas-relief image there shows a shaman dressed in a jaguar skin. According to the K’iche’ Maya creation myth, the Popul Vuh, Seven Macaw was an arrogant, evil bird-god that inhabited the world between the last creation and the present one. Called Vucub Caquix, the vain bird thought of himself as both the sun and the moon. The hero twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque apparently decided that the present world couldn’t be created while Seven Macaw was pretending to be the sun and moon, so they tried to shoot him out of a tree with a blowgun. Although wounded, the demon-bird escaped, shrieking, after severing Hunahpu’s arm. They continued to pursue him and finally killed him, and he became what are now the seven stars of the constellation of the Big Dipper – hence his name “Seven Macaw.” Xbalanque, the twin with the most power to operate in the underworld, was portrayed in some Mayan art as spotted like a jaguar, and his name has been translated as “Jaguar Sun” or “Unseen Sun” – maybe “Unseen Jaguar”. After many further heroic acts, the hero twins were able to defeat the forces of the underworld, reach the surface of the present Earth, and continue into the sky until they themselves became the sun and moon.

A long time ago, participating in a men’s workshop on defining personal values and perspectives, the group leader challenged us in one of the exercises to let our minds go free, and to “find your totem animal.” It sounds a bit flakey and New Agey now, and maybe it was, but it had a significant effect on the lives of many men in that group. Given the challenge, my mind immediately started wandering, and found itself in the dark forests of the American tropics, and I entered into the body-mind of a jaguar. In that long-ago psychological exercise, I felt that a jaguar chose me to take it as a totem animal.

Why conserve jaguars, and the forest expanses they need to survive? The Mayans knew that jaguars are part of our shadow side, our connection to the dark, the night, the unseen, the forest, the power we can’t understand, and the sun and moon as they shine on the present Earth. Landscape species like the macaw and jaguar, besides connecting and unifying the ecological landscapes that we inhabit, also inhabit the cultural and psychological landscapes of human myths and dreams, linking our world with the wider ecosystem of the Cosmos.

Jaguars are watching us. I never saw them, but I knew they were listening at Caracol when the pauraque spirit kept asking “Who are YOOUU?” I could feel their eyes on me as we walked in the dark at Tikal to watch the sunrise from Temple IV. I could imagine them watching us as we swam and sunned in the deep pool below the falls on the Tiger Fern Trail, where they drink in the inky night.

Related links

- A Natural History of Belize: Inside the Maya Forest, by Samuel Bridgewater

- Friends for Conservation and Development (FCD) Belize

- Forest Department of Belize

- The Last Flight of the Scarlet Macaw, book review from Orion Magazine, March/April 2008

- Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary

- Jaguar: One Man’s Struggle To Establish The World’s First Jaguar Preserve, by Alan Rabinowitz. Island Press, 2000

- Jaguars and big cat conservation

May 14, 2014 5:15 pm

Dear Bruce:

Thanks for sharing this nice trip findings, and for the education that brings your writing to the public.

Saludos