June 2021. At about the time the coronavirus pandemic struck in the spring of 2020, I was preparing my application for a writing residency at the Mesa Refuge in Point Reyes Station, California. It was an exciting opportunity I had learned about because several of my favorite writers, including Rebecca Solnit and Robin Kimmerer, are Mesa alums. Mesa suspended the application process for about half a year, but when it opened again, I sent my proposal in November. It was accepted and I was invited to spend two weeks as a resident writer in June.

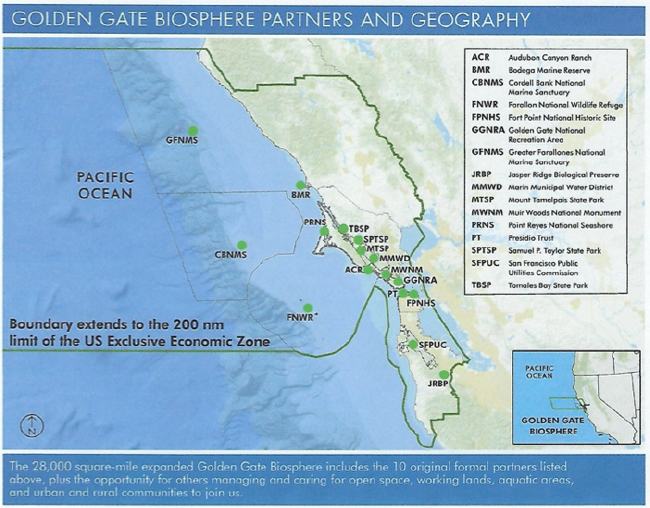

In my proposal, I said that I would use the conceptual framework of “lessons” and “themes” that I developed in my book about Oregon’s Cascade Head Biosphere Reserve (The View from Cascade Head: Lessons for the Biosphere from the Oregon Coast, Oregon State University Press, 2020) to ask how they may apply in the Golden Gate Biosphere Reserve, within which the Mesa Refuge is situated. Compared to Cascade Head, the Golden Gate Biosphere Reserve is huge. Its 28,000-square-mile area, which includes both terrestrial and marine zones, stretches approximately 150 miles along the coast, from Point Arena to Point Año Nuevo. Established in 1988, it is one of the most complex, sprawling, diverse and ambitious of any of the 28 biosphere reserves in the United States. Its stakeholders and partners include two large national marine sanctuaries, Greater Farallones and Cordell Bank, which protect the marine zone, and various federal, state, and local agencies and non-profit organizations, including the National Park Service, California State Parks, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which conserve and manage its terrestrial areas. It is probably more accurate to call it a “biosphere region” than a “biosphere reserve,” given its size and the complexity of ownership and management of its lands and waters. The Golden Gate Biosphere Region is part of an international network of biosphere reserves designated by UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, which now includes 714 sites in 129 countries. (In my international ecological consulting career, I’ve been fortunate to work in 35 of these, in 17 countries.)

_______

The Mesa Refuge was my base to begin to explore this region’s fascinating geology, ecology, and history. One goal was to experience the landscape firsthand—to hike, look, see, and gather impressions and images to nourish my writing. Another was to meet some of the scientists and conservationists who know the bioregion and are working to protect and restore it. But another goal was just to take time to enjoy and experience the place, to sit and listen to the wind, watch the birds and the sunsets, and let it all sink in.

The environment at Mesa Refuge was perfect for all of that. I shared the common spaces with only one other resident writer. The main house, designed as the studio of an abstract-expressionist painter before becoming a residence for writers, was a charming blend of elegant and rustic, cultured Californian with a touch of Zen temple: wooden beams, open design, high ceilings, windows in all directions, gardens all around. The wall of west windows in the main living room of the house, called the “Gathering Room,” gave light across to an east wall of bookshelves that held the Mesa Refuge library. Looking through the hundreds of books written by Mesa resident authors was both humbling and gratifying; humbling because those volumes represent a lot of cutting-edge thinking and include some of my favorite writers, gratifying because my work will also now share those shelves.

I was assigned my own personal “writing shed,” a small cabin a few steps from the main building, with windows looking out over the restored Giacomini Marsh and Tomales Bay, where white egrets hunted and hawks and vultures circled. The “shed” was simply furnished, with not much more than a wooden desk and narrow table under the windows and a small couch with big pillows; its ceiling and walls were cedar, the smell of wood wonderful. After busy days of hiking, driving, or interviewing, I retreated there in the late afternoons to reflect and write, as the sun sank northwestward over the water and the wind thrashed in the trees, creating a magical space of silver light and sound in which my imagination could expand to its edges.

_______

My analytical framework from Cascade Head proved to work well in the Golden Gate bioregion. It was easy to find illustrations here of what I argued were the three lessons from Cascade Head. What lessons?

- People make a difference. Their stories are unequivocal in showing the importance of inspired, value-based, individual action.

- Ecological mysteries still abound, despite all the knowledge we’ve gained, and this means that the need for research to inform sustainable ecological management is a never-ending task.

- How we think about our place in nature—our worldviews—matter. Worldviews shape our individual and collective behavior and our effects on the biosphere that sustains us, in potentially positive and sometimes negative ways.

Stories illustrating these lessons flowed freely from the people I met, places I went, and documents I read:

People make a difference? Who? John Muir, William Kent, Alice Eastwood, Alfred Kroeber, Alan Watts, Gary Snyder, Shunryu Suzuki, William Burton, David Brower, Anne Kent, Ansel Adams, Paul Ehrlich, Mimi Whitney… oh, this list goes on and on, right up to the present day and including many of the people I met during my time at the Mesa.

More research needed? What? Which of the blue butterfly (Polyommatinae) species found in the region is the closest relative of the extinct Xerces blue that used to exist in the Lobos Valley Dunes in San Francisco, and would it make a good candidate for reintroduction of an ecologically equivalent species in the restored dunes there? How big a threat is Sudden Oak Death to the various species of native oaks, and how can it be managed? How is ocean acidification related to upwelling and climate change in the California Large Marine Ecosystem? Why are kelp forests disappearing, and what can be done to restore them? How can sea otter restoration along the coast be speeded up? How did so many species of manzanitas evolve in California, and is the Franciscan manzanita really that different from the Mount Tamalpais manzanita and other close relatives, in a genetic sense? The list of fun and fascinating scientific questions also goes on and on.

Worldviews matter? Which? The starkly different worldviews and lifeways of Native American peoples and Europeans and Euro-Americans—Spanish explorers and missionaries, Russian fur traders, and American gold-rushers—collided here, starting centuries ago. The indigenous worldviews of the place—Ohlone, Coast Miwok, Pomo—documented by cultural anthropologists like Alfred Kroeber, and brought to life again by Native American storytellers like Greg Sarris, help us imagine another way of being in nature. And Zen Buddhism, a sharp samurai sword cutting into the Western worldview, helped motivate cultural and environmental rebellion from the Beats of the 1950s to the environmental movement of the 1970s. From the San Francisco Zen Center to Tassajara and Green Gulch, zendos have sprung up across the bioregion faster than native salmon can recolonize restored creeks. The worldviews imagined in works of future-fiction set in the region also have helped us picture alternative futures: Ecotopia by Ernest Callenbach (1975), for example, or Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home (1985).

_______

The Mesa Refuge website describes it as “a residency for writers, journalists, and other creatives… focusing on ‘ideas at the edge’ of the areas we value: nature, economic equity and social justice.”

Their phrase “ideas at the edge” immediately caught my imagination. I’ve explored this part of the world a bit before, and knew that Point Reyes Station, a town of about 350 residents, sits right on the infamous San Andreas Fault, at the southern toe of Tomales Bay. To the north, the bay fills the drowned fault valley for fifteen miles to its mouth at Dillon Beach. To the south, the Olema Valley marks the fault line to Bolinas Lagoon, where it goes offshore until it hits and splits the San Francisco Peninsula. To the west, the Inverness Ridge rises up steeply; to the east, the hills of Marin Country roll toward San Pedro Bay and the Sacramento Delta.

The Mesa Refuge is at the edge of two of Earth’s great tectonic plates (the Pacific and North American), the edge of a continent, the edge of land and sea. I liked Mesa’s “ideas at the edge” metaphor. Edges are dynamic places, where change and movement— “stuff” —happens. We talk about the “leading edge” or “cutting edge” of something, usually with a positive connotation. That’s where I wanted to be.

On the “Earthquake Trail” that starts at the Bear Valley Visitor Center of Point Reyes National Seashore, a thought-provoking sign welcomes visitors to the San Andreas fault zone, which it calls “A Shrine to Earth’s Power.” The text seems written to jolt us out of our temporal myopia—our short-sightedness regarding time. Here, on this part of the trail, we walk on the Pacific Plate, which is moving northwest at a speed of around two inches per year. The Pacific Plate has been grinding northwest along the western margin of the North American Plate for 20 million years or so, grabbing bits of the continent as it goes. The granite core that forms the outer point of the Point Reyes Peninsula, with its dramatic cliffs and lighthouse, match granite found in the hills near Santa Barbara, about 350 miles south. It is estimated that about 100,000 slips of the fault the size of the 1906 earthquake would be required to move Point Reyes that far north. The trail leads on under ancient bay laurels until it reaches an old fence; an offset gap of eighteen feet in the fenceline here recorded the movement of the 1906 earthquake, when a couple of century’s slow creep of the fault suddenly slipped all at once.

One day I hiked to the far northern tip of Tomales Point, a granite finger of the Point Reyes Peninsula that points northwest along the fault between Tomales Bay and the Pacific Ocean. From there, looking across the mouth of the bay, I had the feeling of looking at North America “over there;” that I was on another continent and I was waving goodbye as I rode off on the Pacific Plate into the future. This was the wild edge, in time and space and imagination. I couldn’t stay long, the wind was too strong.

The last big slip of the San Andreas, the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, resulted in some important realignments in American nature conservation that are still reflected in the landscape of the area today. The fire in the city following the quake set off a frenzy of water development and rebuilding that almost led to the damming of Redwood Creek, on the southwest slopes of Mount Tamalpais in Marin County, and the cutting of its old-growth redwoods, some of the few left in the area at that time. But through quick and clever conservation action, involving William Kent, Gifford Pinchot, Teddy Roosevelt, and John Muir, it was protected as Muir Woods National Monument in 1908. The water development lobby eventually succeeded in damming the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park, however. a stinging loss for Muir, the Sierra Club, and the American nature conservation movement. Sierran water from Hetch Hetchy now fills the Crystal Springs Reservoir that lies over the fault in the middle of the San Francisco Peninsula, supplying the urban area with water.

_______

Nature makes and has edges. Ecologists call the edges between different habitats or ecological communities “ecotones.” Ecotones are transition zones between biological communities, where their species meet and interact. The term was first coined by Alfred Russell Wallace, co-inventor, with Charles Darwin, of the idea of evolution by natural selection. The “tone” part of the word comes from the Greek word tonos, meaning tension; ecotones are places where ecological forces pull in different directions. A lot is happening at ecological edges. Biological diversity is often high, with species from both habitats mixing. Some species love ecotones—you might call them edge specialists. Crows and jays, gulls and coyotes, raccoons and foxes—and humans, perhaps? But some species don’t like edges; these “interior” specialists like to be surrounded by a lot of the same habitat. Spotted owls, lovers of big, intact, old-growth forests, are one example of edge-haters. As human activities have fragmented natural ecosystems and increased edges, we have often had to put the edge-haters on the endangered species list.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to define the boundaries of any ecosystem; if you push outward, looking for the edge, that ecosystem eventually connects with the entire biosphere. Global warming and ocean acidification are already demonstrating this fact by affecting ecosystems everywhere.

The biosphere is an “edge” between life and the non-living physical world; it may be the only such place in the universe. The biosphere is where the non-living parts of our round planet—the lithosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere—meet and greet and create the mix-up in which life evolved. The term biosphere and the concept behind it were cutting-edge ideas at the time they were developed. The word “biosphere” was first used in something like its modern sense by the Austrian geologist Eduard Seuss, in his book Das Antlitz der Erde, or The Face of the Earth, published in 1885. The term and concept were promoted by Ukrainian geochemist, Vladimir Vernadsky, in a 1926 book, The Biosphere, which was translated from Russian to French in 1929, and soon after to English. The biosphere concept is a cutting-edge idea because it describes how all of life on the planet, and everything we do, are interconnected and interdependent.

And the biosphere concept is not only a cutting-edge ecological concept, it is also—and has been from its beginnings—a radical geopolitical concept. Ecological historian Frank Golley describes Vernadsky’s book as “a scientific expression of a global system of man and nature, which was an antidote to the virulent nationalism that was being expressed at the time, especially in Europe.”

In 1968, with growing international alarm about human impacts on the global environment, UNESCO elevated the biosphere concept in a conference that asserted that environmental conservation and sustainable human development are two sides of the same coin. After the conference, an international network of “biosphere reserves” was organized. The first US biosphere reserves were designated in 1976.

Biosphere reserves are supposed to be special, significant places where the interface between human activities and natural processes and ecosystems can be described, diagnosed, restored, and healed. They are meant to be experimental sites—maybe they could be called laboratories—for understanding and improving the human-nature relationship. Beyond the general parallels with the Cascade Head, the unique ecological, cultural, and historical context of the Golden Gate Biosphere Region promises to demonstrate some important new insights and lessons for healing and harmonizing our relationship with our home planet.

I wanted, at the Mesa Refuge, to do some “edgy” thinking from the edge of the continent. The way the Mesa website described its areas of interest seemed, to me, slightly slanted toward human “economic equity and social justice.” I agree with that, in and of itself. But I tried to use my time there to begin to expand that mission, à la Aldo Leopold, and explore some ideas about equity and justice for the whole biotic community.

For related stories see:

- Report from a Season at Cascade Head, February 2019

- Explorations in Oregon’s Andrews Experimental Forest, December 2019

- More Fun and Philosophy in the Andrews Experimental Forest, February 2020

Sources and other links:

- Mesa Refuge

- The View from Cascade Head: Lessons for the Biosphere from the Oregon Coast (Oregon State University Press, 2020)

- Golden Gate Biosphere Reserve Fact Sheet

- UNESCO Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme

- U.S. Geological Survey. 2005. Geology at Point Reyes National Seashore and Vicinity, California: A Guide to San Andreas Fault Zone and the Point Reyes Peninsula

- Landscapes Revealed (blog). 2020. The Geology of Point Reyes National Seashore

- Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service (official website)

- Point Reyes National Seashore Association

- Muir Woods National Monument, National Park Service (official website)

July 23, 2021 5:24 am

Hi Bruce- another thought-provoking read. Thanks for keeping me posted on your writing. Best- Anne