September 2020. This September marked ten years since I left a job at a consulting firm where I had worked for about five years and restarted the independent consulting business I’d first started in 1994. I wrote about that in 2010 in a story titled “Field of Dreams of Monarchs.” On my last day commuting to the office of my former employer, a fat monarch caterpillar was just beginning to crawl off the milkweed plant beside my house that it had been gobbling for a couple of weeks, looking for a place to pupate. When I got home that evening, I spotted a jade-green chrysalis hanging from an old TV cable that runs low along the east side of the house. “Even if coincidental, watching the start of monarch metamorphosis on my last day of a job that had becoming increasingly unrewarding, and moving on to something new and exciting, was for me very symbolic,” I wrote at the time. About a week and a half later, on a bright and sunny, commute-less morning, I watched an adult butterfly emerge from that chrysalis. Free at last!

That year my side-yard monarch “ranch” raised at least 18 butterflies bound for Mexico. For many years after that 2010 fall season, I saw very few adult monarchs in my yard or their larvae on my milkweeds, and only in a few years saw a larva mature to the fat fifth-instar stage, ready to pupate. The milkweed thrived though, living up to its name “weed,” as its downy seeds drifted around my yard and the neighborhood, sending up new plants in my lawn and my neighbors’ lawns too. Joe-Pye Weed (Eutrochium fistulosum), a tall pink-flowered native plant I’d planted as a nectar flower for monarchs and other butterflies, was also thriving and spreading. This looked like good monarch habitat, albeit a small, isolated patch of it in a suburban sea.

In October, 2012, I wrote that “The milkweed I planted two years ago, which hosted such an active monarch population then, had spread this year, and lots of healthy plants promised a feast for monarchs. But the monarch ‘field of dreams’ was deserted and sad. In September, when there had been so many hungry monarch larvae on my milkweeds two years ago, there were none. What happened to the monarchs in Falls Church this year? In ecology, and in life in general, a lot is due to chance. Living systems combine processes and relationships that are well understood with events that are intrinsically non-deterministic, sporadic, and random. This makes it very difficult to understand the behavior of complex ecological systems, much less predict them.”

Two years ago, in September of 2018, I wrote a “reprise” to my 2010 story, “Monarch Field of Dreams: Reprise.” I was just about to leave for a four-month stay as the resident ecologist at the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology on the Oregon Coast. That year I reared 14 monarch larvae from the milkweeds in my yard in an old aquarium with a screened top, protecting them and feeding them sprigs of milkweed until they pupated, and then watched them eclose from their chrysalises and head off on their journeys to Mexico.

In late September last year, 2019, I was again headed to Oregon, and, not wanting to commit the time to rearing the monarch larvae that I found, I decided to let nature take its course. As in many years between 2010 and 2018, I had seen very few adult butterflies and found very few larvae. The small ones all seemed to disappear, and only one managed to make it to the fifth-instar stage. I kept my eye on it, hoping I could find its chrysalis once it pupated. But one morning, a few days before I left, I found the limp shell of the caterpillar, like a striped sock, on the ground under the milkweed where it had been grazing the previous afternoon. Its insides had been sucked out by an assassin bug, which I spotted gloating on the leaf where the larva had been. “Damn!” I thought. Letting nature take her course was a reminder that nature can be “red in tooth and claw”—or the assassin bug equivalent thereof. Assassin bugs (Zelus spp.) are common predators in what has been called the “milkweed ecosystem.” They stab caterpillars with their needle-like proboscis, inject saliva that liquifies their insides, and suck their juices out, leaving the outer skin—just what I’d found that morning.

This year, 2020, after seeing last year’s small crop of monarch larvae disappear and the one that made it to fifth instar get sucked dry by an assassin bug, I decided to take a more active role to protect “my” monarchs; I decided to assist nature by reviving my monarch ranching. I got out the old aquarium with its screened top, and started bringing larvae into that simplified, predator-less (or so I thought) ecosystem, where they could safely nibble the sprigs of milkweed I provided and grow up to pupate and emerge.

But right away I got another lesson in the hazards of monarch life. Of the first seven larvae I brought into the aquarium, one turned jet-black just after it formed its chrysalis, and never emerged. Another big fifth instar crawled up the glass toward the screened top as if going to pupate, but stopped halfway up and went limp, never to move again. A third made it to the screen, spun the silky cremaster by which the chrysalis is attached, but then went limp before going into the “hanging J” phase; it never formed a chrysalis.

A couple of days later, I noticed ten little white maggots squiggling around on the floor of the aquarium under the dead, hanging caterpillar; each was about the size of a grain of rice. Each soon formed a hardened pupal case that darkened to brown, then black. That’s weird, I thought. Out of curiosity, I put them in a jar with a gauze cover, and waited. About 10 days later, the jar was abuzz with tiny black flies that looked something like houseflies. Now that was quite a transformation: from butterfly to flies! If metamorphosing monarchs, dreaming in their jade chrysalises, have nightmares, that would be one of them!

A little online research taught me that these were tachinid flies, common parasites of butterfly and moth caterpillars of all kinds. It turns out that one species of tachinid, Lespesia archippivora, is a significant parasite of monarchs. They lay their eggs on monarch larvae, into which the fly maggots burrow once hatched, eating the larva from the inside—and killing it, of course.

Karen Oberhauser, a monarch ecologist and now the director of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum, used data from citizen-scientist observers to get a picture of the level of parasitism of monarchs by Lespesia archippivora. The study area spanned at least a dozen upper midwestern and southern states and one Canadian province, and 13 years. In a 2007 summary article, Oberhauser and colleagues reported that an average of 13 percent of monarch larvae were killed by tachinid flies. Parasitism rates varied by year. The proportion of monarch larvae parasitized by L. archippivora ranged from zero to 43 percent. In some years, regional rates of tachinid parasitism were up to around 30 percent, and a few years later could be near zero. With that kind of variation, maybe it isn’t so surprising that in other years I hadn’t seen tachinid flies kill the caterpillars I was rearing. Bringing larvae into a screened aquarium when they are very small would, of course, help protect them from the flies, and that could also explain why I hadn’t witnessed this kind of monarch nightmare before. Oberhauser’s study found that approximately 80 percent of the monarch larvae collected and reared eventually emerged as adult butterflies, though, so monarchs seem to have a pretty fair chance of surviving their predators in the milkweed ecosystem.

Is there a moral lesson here, a lesson about “taking sides”? If anything, the lesson is that ecosystems are bound together in mutual interdependence by energy and nutrients flowing in food chains and food webs. As much as I love monarchs and delight in their amazing life cycle and migration, they are only one part of the milkweed ecosystem. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who used the phrase “red in tooth and claw” in his 1850 poem, In Memorium, wrote in that poem:

She [= Nature] cries ‘a thousand types are gone:

I care for nothing, all shall go.

Thou makest thine appeal to me:

I bring to life, I bring to death: …’

Californian poet Robinson Jeffers put a more positive face on nature’s seeming indifference to the yin-yang of life and death, saying “the greatest beauty is organic wholeness, the wholeness of life and things, the divine beauty of the universe.” Monarchs, milkweeds, tachinid flies, assassin bugs: all part of that wholeness and beauty.

I’m glad to know about assassin bugs and tachinid flies, but I don’t feel guilty for my assistance to the monarchs. I was able to watch and record the exact moment of eclosion of one butterfly, which you can watch here:

Monarch Eclosing, 24 September 2020

It was a brief, transformative moment like that I’d seen on that morning a decade earlier. This year my milkweeds and aquarium-rearing technique saw 21 butterflies through their metamorphic transformations from larvae to chrysalises to adult butterflies.

Over the years I’ve reflected on monarchs many times, often writing about my observations of their migration at Cape May, New Jersey, where the state points a finger of land down through the Pinelands, past Atlantic City and the Wildwoods, to the mouth of Delaware Bay. Any flying creature heading south for the winter, whether birds or monarch butterflies, pause at Cape May, fuel up, and get up the courage to launch out over the bay mouth to Cape Henlopen, Delaware, 14 miles away.

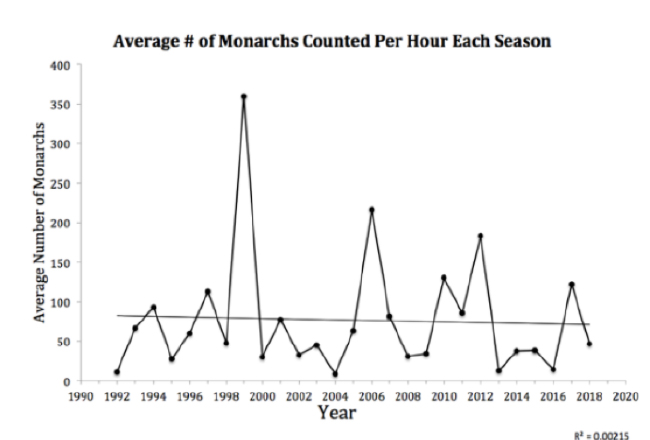

In October, 2011, I wrote: “Sipping coffee on my 5th Floor balcony at the Ocean Holiday Motel, overlooking the dunes and beach at Wildwood Crest, New Jersey, on Columbus Day, the scientist in me couldn’t resist even an amateur attempt to quantify the surprising flow of monarch butterflies going past at this “altitude.” I started the timer on my digital watch, and started counting. In ten minutes, I was ready for a refill, and 20 monarchs had flapped and soared by – an average of one every 30 seconds.” The Cape May Bird Observatory (CMBO) is famous for its annual “watch” and count of migrating hawks, and a spinoff, the CMBO Monarch Monitoring Project, has been monitoring monarch numbers since 1991, making it the longest continuous quantitative study of migrating monarchs in the world. The project conducts a census of passing monarchs on a standard transect, and so can compare numbers from year to year. In my post from October, 2013, a story I called Peregrination to Cape May for Hawks and Monarchs, I described how the monarch-monitoring data seemed to show that monarch numbers at Cape May (reflecting their population in eastern North America) were climbing back up from a record low in the fall of 2004.

After years of making a faithful fall pilgrimage to Cape May, I didn’t make it back several years after that, until October, 2017, when I wrote that “One of the blessings of trying to observe natural phenomena is that we are not in control – nature is. We can hope that the hawks or butterflies will be at their peak, but all of us are caught up in a complex system we can’t control or hardly even predict, and that experience of being embedded in a complex ecological world is humbling – or should be. In 2011 on almost the same date, as I sipped my morning coffee, I watched a steady flow of monarch butterflies – an average of one every 30 seconds according to my informal tally – heading south past the ocean-facing balcony of my 5th-floor room at the Ocean Holiday Motor Lodge in Wildwood Crest, New Jersey, just north of Cape May. This year, nothing. Monarchs and hawks take advantage of cold fronts pushing strong winds that carry them south, but this year former Hurricane Nate, now a tropical depression, was lollygagging up from Louisiana, spinning a strong flow of unseasonably warm and humid air to Cape May on steady breezes from the south. Sipping my coffee on the balcony of Room 512, I was sweating in shorts and T-shirt, and not seeing any butterflies.” But just a week earlier, in the wake of a passing front from the north, the CMBO Monarch Monitoring Project Reported: “Wow! What a weekend in Cape May. This has been the biggest year since 2012.” Their driving census on Saturday, September 29th, was 279 monarchs per hour, and a point-count in the dunes was over 700 per hour. That rate of migration would be several multiples of my 2011 Ocean Holiday point-count of 120 monarchs an hour. Wow was right! That must have been spectacular.

I haven’t been back to Cape May for the hawk and monarch migration since 2017. In October, 2018, and again in 2019, I was in Oregon, enjoying writing residencies at the Sitka Center and the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, respectively. This year, the coronavirus pandemic has pinned me down and completely curtailed my travel, except to the grocery store once a week wearing a mask.

Monarch monitoring at Cape May is underway this fall (2020) however, and the CMBO Monarch Monitoring Project has posted data from early September so far: “During this year’s first week (Sept. 1 – 7), the average was 12.5 monarchs sighted per hour (see chart, below). This ranks 18th for week 1, meaning 17 years have seen a higher average and 11 have seen a lower one. It’s still too early to predict if the whole season will be above or below the long-term average, which is why we continue to count monarchs several times, every single day, during our two-month field season.” In the project’s graph, below, note the slight—actually quite slight—downward slope of the average since 1992; but also note the dramatic fluctuations.

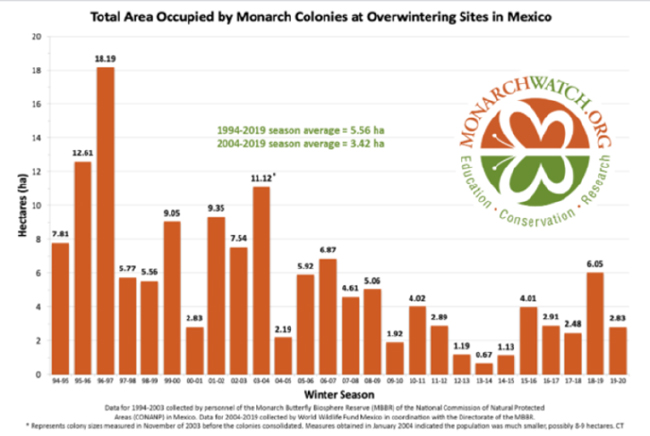

One benchmark of the status of the monarch population is the area occupied by their overwintering colonies in the mountains of Michoacán, Mexico. I wrote about a visit there in March, 2004. Monarch Watch, a monarch science and monitoring organization, reports these statistics. The most recent data, up to the 2019-2020 winter, are shown in the graph below. It’s interesting for me to compare my “backyard” experience with monarchs over the decade from 2010 to 2020 with these data from Mexico. When my fledgling “monarch field of dreams” in 2010 launched at least 18 monarchs Mexico-ward, the area occupied by monarchs there was about four hectares—about 10 acres. Tiny, even then—but these overwintering roosts are incredibly dense! Last winter’s roosts in Mexico were about three-quarters as large.

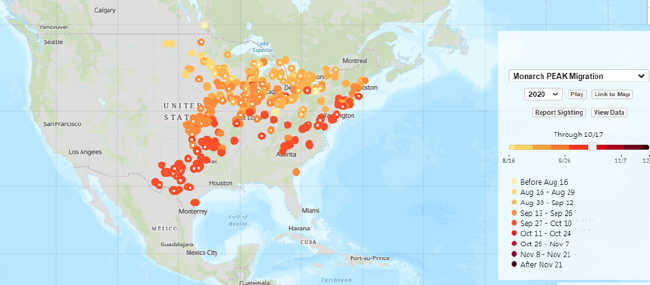

This year—my backyard having launched 21 monarchs that I know of—my scientific prediction would be that the overwintering area will be as large as that of the winter of 2010-2011, or maybe just a bit larger. But it’s a long journey from my backyard to Michoacán—2,000 miles, very roughly. And there could be a lot of unpredictable weather to travel through, from cold fronts to late-season hurricanes. The Journey North project, hosted by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum, compiles observations of monarchs by citizen scientists. Amateur observers from Mexico, the United States, and Canada report monarch sightings at all stages of the life cycle, from egg to adult, track the migration, and observe the overwintering colonies in Mexico. The results are published online in a biweekly map allowing us all to visualize the seasonal flow and movements of monarchs across the continent. Wonderful! The latest map shows them retreating from their summer habitat in the north, and well on the way to their winter home in Mexico.

I imagine the monarchs from my yard joining this flow as they retreat south from the coming cold to those cool refugia of oyamel fir, where they will wait in hope for a new year and a new journey north.

For related stories see:

- Field of Dreams of Monarchs. October 2010.

- Migrating Hawks and Monarchs, Cape May, New Jersey. October 2011.

- Pilgrimage to the Monarch Butterfly Overwintering Refuges in Michoacán, México. March 2012.

- Cape May Hawks and Monarchs. October 2012.

- Peregrination to Cape May for Hawks and Monarchs. October 2013.

- Monarchs and Hawks at Cape May. October 2017

- A Morning at the University of Wisconsin Arboretum in Madison. July 2018.

Sources and related links:

- Huber, Kate. 2014. Monarch butterflies depend on the milkweed to survive, but other insects also call it home. Houston Chronicle, September 19, 2014.

- Journey North

- Oberhauser, et al. 2007. “Parasitism of Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus) by Lespesia archippivora (Diptera: Tachinidae).” The American Midland Naturalist 157 (2): 312-328.

- Oberhauser, Karen. 2012. “Tachinid Flies and Monarch Butterflies: Citizen Scientists Document Parasitism Patterns over Broad Spatial and Temporal Scales.” American Entomologist, 58 (1): 19–22.

- Tennyson, Alfred, Lord. 1850. In Memorium A.H.H.

- Cape May Bird Observatory Monarch Monitoring Project

- Monarch Watch

October 18, 2020 7:54 pm

Hope I responded to this latest (terrific) essay. Do have some “age-related” CRS (can’t remember stuff).

Hope all’s still well with you.

dave armstrong

October 27, 2020 11:37 pm

Great article! Thanks.

November 13, 2020 4:26 am

One observation that I made was the size of the screen on your aquarium. It does not look parasite proof. Flies can lay through that type of screen when a caterpillar is molting or in its J. Also assassin bugs can pierce caterpillars. I don’t know if your container is inside or out. I would recommend an extra layer of protection. A layer of noseum screen would prevent any parasitization. Make sure to use parasite proof cages outside or even inside. Frass (butterfly poop) attracts predators. They will follow you inside.

I truly believe if we can create a dense, diverse garden that nature will allow some of the Monarch caterpillars to succeed in the wild. Wild Monarchs are more successful at migrating to Mexico. Keep it wild and keep them local. Monarchs are amazing, so are all the pollinators. I am located in Herndon, Virginia.