October 10, 2011

Sipping coffee on my 5th Floor balcony at the Ocean Holiday Motel, overlooking the dunes and beach at Wildwood Crest, New Jersey, on Columbus Day, the scientist in me couldn’t resist even an amateur attempt to quantify the surprising flow of monarch butterflies going past at this “altitude.” I started the timer on my digital watch, and started counting. In ten minutes I was ready for a refill, and 20 monarchs had flapped and soared by – an average of one every 30 seconds.

Something was up today: the previous two days had been much slower and quieter. Some monarchs, sure, but nothing unusual. Today was much more active.

At the Hawk Watch platform at Cape May Point it was clear that something was up also. A swirl of monarchs was going over the platform and the parking lot, a dozen at a time in the lower field of binoculars turned skyward. And above them, the hawk flight was hot too. Saturday and Sunday had both been slow as far as birds go, although the human crowd was high on Saturday, and peaked on Sunday. Today many of the Jersey weekenders had headed home, but because of some subtle quirk in the winds and weather, the hawks and monarchs were on the move.

But now, a bit of context: New Jersey? Are you serious? Most of us don’t think of New Jersey when we think of hotspots of biodiversity conservation. But for eastern North America, for hawks and monarch butterflies, it is such a focal point.

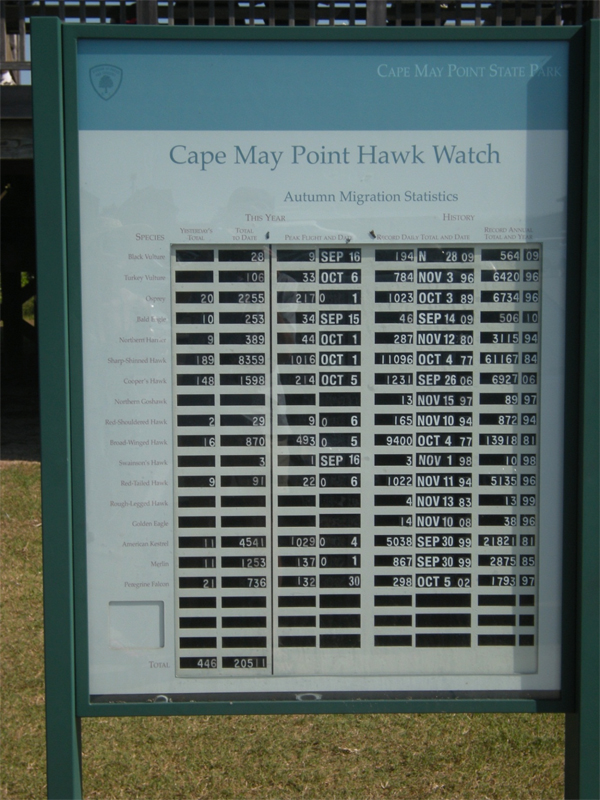

A look at the map of the east coast of North America gives the first hint. Because of the shape of the coastline, any bird, or butterfly, heading south in the fall from a big chunk of northeastern North America – anywhere from Newfoundland and Quebec to Maine – will find itself funneled to Cape May, New Jersey. Funneled through Wildwood Crest, a beach town with its classic 1950s and 60s “Doo-Wop” era motels, from the balcony of one of which I had conducted my breakfast monarch count. Funneled past the Victorian hotels and mansions of Cape May, to “the Point”: an arrow of sandy land aiming across the mouth of the Delaware Bay, separated by fourteen miles of water from Cape Henlopen, Delaware, where the coast continues on south. At this point, birds and butterflies alike pause, put down to feed, and rest and regroup for the crossing and the next challenges of the journey south. This concentration of migrating hawks has been recognized for over a century, and in 1976 the New Jersey Audubon Society’s Cape May Bird Observatory (CMBO) began its annual hawk count. Between September 1st and November 30th, an average of 60,000 birds of prey have been counted passing Cape May Point over these years. The count gives a basic summary of the health of raptor populations – and by extension their prey species and their natural habitats – over a large part of northeastern North America. The annual hawk count is a partial answer to the question: How is nature doing in this part of our continent?

So here we humans stand and marvel at them; wonder at the forces that impel them on their journey; and ask ourselves what this means for us, and whether we can learn anything here that will inform our own wanderings and migrations.

“Kettles:” of raptors – swirling groups of hawks circling in the vortices of thermals to get lift up to altitudes that would help them slide across the mouth of the bay to Delaware – boiled up against the sky. Some were nearly pure groups of one species: ten or a dozen Broad-winged Hawks, for example, or four Bald Eagles. Others were integrated: a Bald Eagle, an Osprey, a Northern Harrier, two Broad-Winged Hawks, and a Peregrine Falcon. Peregrines stroked by in their deliberate flight. Turkey Vultures soared without a wingbeat, around and around, apparently in no hurry to go anywhere.

Looking up at the hawks through binoculars, in the foreground, like the stars in our own galaxy, were the constellations of monarchs. The CMBO Monarch Monitoring Project has been monitoring monarch numbers here since 1991, making it the longest continuous quantitative study of migrating monarchs in the world. Dick Walton, the director of the project, told me that this year monarch numbers have been low.

That correlates with my observations in Falls Church, Virginia. Compared to last year, when my side-yard monarch “ranch” raised at least 18 butterflies bound for Mexico, this year I saw only one 5th instar larva on my milkweeds. I saw a few other larvae of earlier instars, but never saw them get bigger and mature. Here in Falls Church we were confronted with exceptional heat in July, Hurricane Irene in August, and a record-setting dump of rain from Tropical Storm Lee in September. Compared to last year, this apparently wasn’t monarch weather.

However, since everything in the ecological world is connected to everything else, the cause of this year’s low monarch numbers throughout the northeast and mid-Atlantic may have linked back through earlier generations and wider geographies. This year the first generation of monarchs flying out of Michoacán, Mexico, back in March may have encountered the drought in Texas, and not been able to build up a very big population to fly on northward. Whatever the causes, this year my monarch ranch was very unproductive, compared to my first year, last year.

But despite low numbers of migrating monarchs at Cape May this year, they continue to flow past the point on the journey south. Louise Zemaitis, the CMBO Monarch Monitoring Project Coordinator, said that last week, when conditions were just right, they counted about 600 monarchs an hour leaving the Point to cross the Delaware Bay. On the Cape May to Lewes, Delaware, ferry this afternoon, we encountered a pocket of monarchs over the water, about three-fourths of the way across the 14-mile crossing. About once a minute a monarch would appear on the upper deck of the ferry, and flap into the lee of the wheelhouse, where it would linger in the still air, but not land. After a minute or so of flapping around the passengers sitting on benches in the late sun it would flap up and get blown back behind the moving ship, making its own way on across the bay. That image of spontaneous encounter in the middle of the crossing, and of the strength and self-sufficiency of those monarchs, sticks with me still. With that internal fortitude and compass, monarchs will be fine, as long as we give them room to roam, and habitat to roam in. They may be fine long after we are, come to think of it.

Related links:

- http://www.birdcapemay.org/index.html

- http://www.birdcapemay.org/monarch.shtml

- http://www.learner.org/jnorth/maps/monarch_f11_all.html

- http://www.doowopusa.org/district/index.html

November 8, 2013 2:10 am

[…] Migrating Hawks and Monarchs, Cape May, New Jersey […]