About a year ago, in October 2016, I was in Quelimane, Mozambique, a small city on the central coast and the capital city of Zambezia Province. Quelimane is located in the delta of the Rio dos Bons Sinais, as the Portuguese explorers named it – the “River of Good Signs.” The U.S. Agency for International Development, USAID, is helping the city to prepare for global climate change through its Coastal City Adaptation Project, or CCAP (“see-cap”). CCAP began its work in 2014 in two coastal cities, Pemba and Quelimane, and in Quelimane mangrove restoration was an important component.

I was there as team leader for a midterm evaluation of CCAP, contracted through ECODIT, a small consulting firm based in Washington, DC. Two Mozambican consultants and a climate change specialist from the U.S. rounded out the evaluation team. The project is challenging and complicated, and our evaluation identified some weaknesses as well as successes. My philosophy is that the primary purpose of evaluations is to learn: to learn what worked, what didn’t work, and how to improve the project. As you might guess, project implementers welcome the success stories, but often resent the critical findings, and this case was no different. So, I wanted to wait a bit before sharing this story. I wanted to see whether our recommendations for improving CCAP, and in particular its mangrove restoration component, were listened to and acted upon.

Having made a career of assessing challenging conservation situations and evaluating programs, I have always wondered whether my work has made any difference at all. In this case, to informally evaluate the effects of our evaluation of CCAP, I recently contacted several people responsible for the project and asked them whether they had done anything in response to our recommendations about CCAP’s mangrove restoration work. Their responses encouraged me to think that the evaluation had led to changes that will improve mangrove restoration in Quelimane, and so I feel free to share the whole story now, a year later.

——-

We flew from Maputo to Quelimane on LAM, Linhas Aéreas de Moçambique, the national airline. Descending to the airport we got a good view of the lay of the land and the winding Bons Sinais River. We checked into our hotel on a hot and windy afternoon, and had an interview in the hotel courtyard with a representative of one of the project’s partners as the tropical dusk descended rapidly and the mosquitoes came out. Then hunger drove us off through the dark streets, led by Rui Mirira, one of the Mozambican members of the team who was familiar with the city, to find a little seafood restaurant by the river that he said had some of the best and freshest prawns in town. It didn’t look like much, but they had cold 2M – “Dois M” – beer, and the large grilled prawns were indeed wonderful. The Bons Sinais sucked at its banks a few steps from the door.

——-

After a 2012 trip to Angoche, another coastal town about 350 kilometers north of Quelimane, I wrote a story titled “Mangroves in Mozambique: Green Infrastructure for Coastal Protection in an Era of Climate Change.” On that trip, I was leading a team in an “environmental threats and opportunities assessment” for USAID-Mozambique. We went to Angoche to learn about a project being implemented by WWF and CARE that was working with poor coastal communities to protect natural resources. One of their initiatives was mangrove restoration. Based on what we saw in Angoche, in our final assessment report we recommended that USAID incorporate mangrove conservation and restoration into the CCAP project, which it was just then designing. We wrote: “Mangrove conservation and restoration represents an important opportunity to demonstrate the value of an ecosystem-based approach to climate change adaptation. The physical protection from cyclones, winds, waves, and storm surges that mangroves provide, and their ability to trap and hold sediment and thereby build land, are ecosystem services that increase the resilience of coastal communities.” We recommended that mangrove conservation and restoration be a much stronger component of the CCAP program than was then planned and that one or more additional cities be chosen “in which mangroves may provide the main infrastructure for coastal city protection.” I was happily surprised when USAID and CCAP adopted our recommendation in Quelimane. That was the clearest example yet, in my long experience doing these kinds of assessments for USAID, of a recommendation being incorporated into the design of a future project, so of course I was pleased.

However, in that 2012 environmental threats and opportunities assessment report, we also warned that ”mangrove restoration is needed in many places, but the silvicultural science of how to restore each of the main species (there are nine species in Mozambique) in its proper intertidal zone is not complete.” In the story posted as a blog, I stated that warning as: “Although planting mangrove ‘droppers’ – the already-sprouted dispersing seeds of these trees – is easy and effective for some species, more pilot work on mangrove restoration is needed.” Although USAID-Mozambique and their Coastal City Adaptation Project adopted our idea of mangroves as “green infrastructure” for climate change adaptation, here in Quelimane I began to wonder whether they had noted the caveats in our 2012 recommendation: that the science of mangrove restoration is incomplete and that pilot studies are needed to figure out how to do it most effectively.

——-

Mangrove restoration supported by CCAP began in Quelimane in April 2015, Seedlings of Avicennia marina, the most common mangrove species in the area, were grown in plastic tubes and then planted in the intertidal zone. Planting was done in areas adjacent to the neighborhoods of Icidua and Mirazane that were designated by the Municipality of Quelimane as “Areas of Environmental Conservation,” intended for “restoration and protection of mangroves.” Mangroves that formerly covered these areas had been destroyed by the construction of salt-making ponds, in which seawater is evaporated to make salt, or by cutting for firewood. For reasons that we were not able to discover, the communities dug furrows in the mud of the areas to be replanted, as if these were crop fields for familiar crops like maize and cassava. Approximately 13 hectares (about 32 acres) have now been planted with CCAP support.

Mangrove seedlings planted in furrows near Mirazane neighborhood of Quelimane; note some natural regeneration at top of photo

The furrows were not a standard practice for mangrove restoration anywhere in the world. In fact, such a disruption of the natural surface changes tidal flows and probably reduces the survival of planted mangroves. Science-based best practices for mangrove regeneration developed from worldwide experience generally recommend, as a first step, removing dykes and artificial drainage canals to restore the natural intertidal hydrological regime, thereby creating conditions for the natural regeneration of mangroves. Mangroves are perfectly adapted to colonize appropriate habitats, so restoring natural tidal flows generally makes planting mangroves unnecessary as a restoration technique.

In his 2010 article, artfully titled “Mangrove Field of Dreams: If We Build It, Will They Come?”, Robin Lewis, a mangrove restoration scientist based in Florida, wrote that ”Successful mangrove forest restoration should be routinely successful if a few basic ecological restoration principles are applied at the early planning stages.” Lewis has proposed six steps for restoring mangrove ecosystems. Step 1 is to understand and restore the natural tidal flows of the area so that natural regeneration can take place. Step 6 is: “Only utilize actual planting of propagules, collected seedlings, or cultivated seedlings after determining that natural recruitment will not provide the quantity of mangroves desired.” In its eagerness to involve local communities in mangrove restoration, CCAP had not followed these principles.

In my recent follow-up inquiries, however, I learned from a contact at USAID/Mozambique that “CCAP redesigned the mangrove restoration work since we received your report last January. The project completed a new technical evaluation and hosted a workshop in April 2017 to realign the mangrove work with best practices.” I was happy that he added “Thank you for your work and continued interest in this!” The CCAP project director wrote that “We are following the recommendation you provided and have developed an action plan which was submitted to USAID’s program office.” She noted that because of our evaluation recommendations, they suspended their mangrove restoration activities, and organized a workshop with local and national stakeholders to discuss internationally-accepted methods for mangrove restoration. A task force was created to support the application of mangrove restoration best practices in Quelimane and in other coastal cities, and a local organization was contracted to implement the hydrological restoration of the areas where mangroves are to be restored. I’m encouraged that our findings and recommendations were listened to and acted upon!

Evaluation team members Ariane Dinis and Rui Mirira interviewing a local CCAP coordinator at a mangrove restoration site in the Mirazane neighborhood of Quelimane

A mangrove hydrological monitoring system was designed and installed in 2015 in the CCAP mangrove restoration area in the Icidua neighborhood of Quelimane with the help of experts from the U.S. Forest Service. The objective of the monitoring system was to test whether mangrove planting would restore the ecosystem services that mangroves provide. In Icidua, residents complained that the water in their wells sometimes became salty and made them sick. The dense, tangled root systems of mangroves have been shown to act like a dam, trapping freshwater and raising the water table on the landward side, and preventing the encroachment of saltwater into the water table from the seaward side. The monitoring program was designed to evaluate trends in the depth of the water table and the salinity of groundwater as mangrove restoration progresses, and compare the water level and salinity in the restoration area to that in an undisturbed mangrove ecosystem. That information would provide evidence about whether CCAP mangrove planting is restoring the hydrological regime to its functional natural state. When we were in Mozambique in October 2016, it appeared that the monitoring program had experienced significant problems with malfunctioning or stolen equipment and with data collection and analysis, and we could not determine whether it was still functioning as planned or not. My recent follow up about this with the U.S. Forest Service specialist who designed the monitoring system was discouraging. “I have not had any follow-up from the project, so I don’t know if your recommendations etc. were acted on,” he wrote. I think this monitoring program is one of the most important aspects of the CCAP work on mangroves, and I hope it is still being supported adequately.

Girl in Icidua drawing water from an open well; mangroves reduce saltwater intrusion into the water table

——-

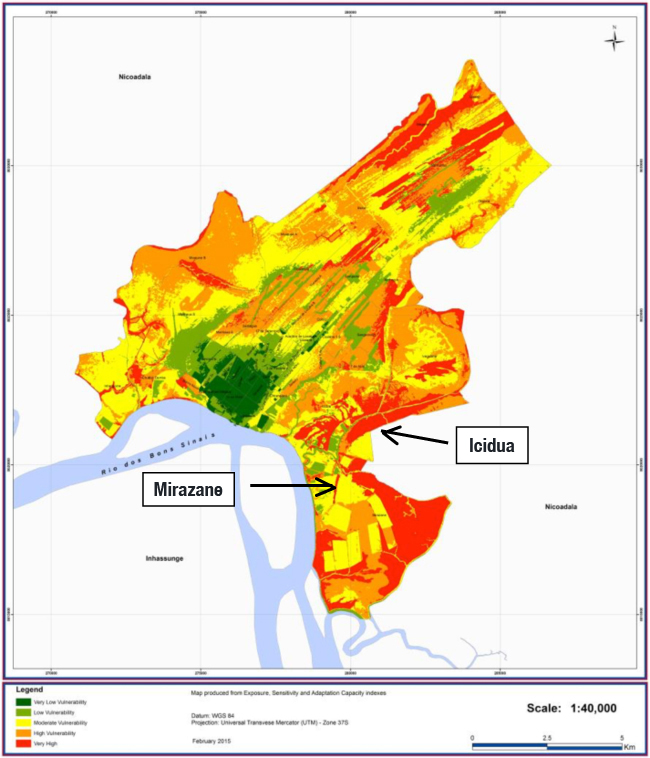

The CCAP Project supported the development of climate change vulnerability maps in Quelimane and Pemba. The maps were developed by looking carefully at the various factors that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change uses to define vulnerability. For Quelimane, the map shows both Icidua and Mirazane neighborhoods in the “red zone” of “very high” vulnerability. Both of these communities are situated on land only a few meters above sea level and are therefore highly vulnerable to flooding from high tides and storm surges associated with tropical cyclones, and from rising sea level.

Climate vulnerability map for Quelimane Municipality from CCAP: Icidua and Mirazane are areas of “very high” vulnerability to climate change risks

This raises some deeper questions about climate change adaptation efforts, both ecologically-based adaptation such as mangrove restoration, and also other kinds of interventions. How can we balance short-term “band-aid” responses with long-term solutions? What is the best strategy for reducing vulnerability to climate-change-linked risks in the long term – for truly increasing resilience to climate change?

To reach Mirazane from Quelimane, we had to cross a branch of the Bons Sinais River on a bridge that was tilted and collapsing, now used only by pedestrians and bicycles. Not a “Good Sign”! We parked on the landward side, walked across, and hired motorcycle “taxis” to take us the several kilometers on to Mirazane, situated on a low sandbar in the middle of the mangroves. This was one of the poorest communities I’ve ever seen – and I’ve seen my fair share of down-and-out places. These fisher-farmers were planting cassava – a crop that supplies nothing but calories – in the sand. Many children here had the telltale rusty hair color caused by kwashiorkor, protein malnutrition. But just in front of the village was one of CCAP’s mangrove planting sites.

The question that comes up is this: is mangrove restoration here really a long-term strategy for climate change adaptation? Or does it only encourage people to stay here a little longer, in the face of what will become an untenable situation? The acting mayor of Quelimane, a public health expert by training, told us that his opinion was that people should not be living in Mirazane or Icidua, and that the city should not be doing anything that would encourage them to stay there, whether rebuilding bridges to the area or planting mangroves.

In places like Mirazane and Icidua, which may become uninhabitable in a generation due to sea level rise and an increasing frequency of extreme events like tropical cyclones, any incentives for people to settle or stay, and not seek less vulnerable areas, could be seen as counterproductive. If the Municipality of Quelimane decided to repair the collapsing bridge to Mirazane, for example, that would potentially reduce the risk to the community during a tropical cyclone by giving residents a more robust evacuation route or giving disaster responders better access. However, it could also encourage the current population to stay in a highly vulnerable area that is becoming more and more vulnerable, and even perhaps entice more people to move there. Repairing the bridge, although it might promise a short-term reduction in risk, would in the long-term make more people more vulnerable to unavoidable climate hazards.

——-

The Mozambican mangrove experts from Eduardo Mondlane University estimate that approximately 5,700 hectares of mangroves exist near Quelimane, and that about one-half of the original mangroves have been cut, cleared, or degraded. Mangroves are still being cut faster than they are regenerating throughout the area. Given these facts, it is difficult to imagine how the restoration of the 13 hectares of mangroves near Icidua and Mirazane supported by CCAP will make a significant contribution to restoring the loss of ecosystem benefits to these extremely vulnerable communities, when the loss of mangroves in the area is around 200 times as large. The mangrove hydrological monitoring program designed by the U.S. Forest Service – if it were functioning – might surprise us, and demonstrate that in fact there can be valuable local hydrological benefits even from very small scale mangrove restoration. However, the ecological scale needed for a sustainable mangrove management plan that would restore a significant fraction of degraded mangrove ecosystems, and provide sustainable mangrove ecosystem products and services throughout the area, would probably need to encompass the entire delta of the Bons Sinais River.

Google Earth view of intact and degraded mangroves near Quelimane, showing locations of Icidua and Mirazane. Image shows an area of approximately 12.8 km X 8.0 km.

So, here’s another case study of the complex challenge of restoring mangroves and the ecosystem services they provide. I think we are learning, slowly, how to do it better, and I’m encouraged that the recent updates I got about the CCAP project suggest that our evaluation may have played a small role in that process. I only hope that our learning curve can keep ahead of the rising sea levels and increase in severe storms that anthropogenic climate change is causing, in Mozambique and around all of the mangrove coasts of the world.

For related stories see:

Sources and related links:

- Coastal City Adaptation Project (CCAP), implemented by Chemonics International.

- ECODIT

- Mozambique Environmental Threats and Opportunities Assessment Report. January 2013.

- Mangrove Restoration website

- Lewis, Roy R. 2010. Mangrove Field of Dreams: If We Build It, Will They Come? Wetland Science and Practice, March 2010.

- Lewis, Roy R. 2009. Methods and Criteria for Successful Mangrove Forest Restoration.

January 29, 2018 4:08 pm

Really encouraging to learn that an evaluation was listened to! A lot depends on the investigators continued interest and involvement.

January 30, 2018 5:37 am

This story brings to the surface the stark reality we frequently choose to avoid – that conservation always involves separating a key resource from people (spatially or temporally, the distance or length of time can be debated). Strong proponents of community-based conservation are the most evasive of this basic truth. If the ecosystem services provided by mangroves at Quelimane are to be restored and/or enhanced, then people have to give way one way or the other, a fact so well admitted by the acting Mayor. They do not have to be removed for all time, or be evicted violently, and if they can already see the bleak future, I think they would understand the need to leave. But do they have alternative places to go? I am afraid a lot of times the answer to this question is no, but this is only because providing alternatives poses serious challenges to governments. Conservation, and governments are naturally the biggest players here, makes little sense without a long-term perspective. Governments usually have to think in the short-term, yet we should not ever be tempted to shy away from advocating what is only a reality.

On the other issue regarding communities digging furrows in the mud of the areas to be replanted with mangroves, the explanation looks quite straightforward to me based on own experience with evaluating projects. The local people were probably called in without any guidance on how the restoration could best be done (obviously because the project implementers did not know either). There may also have been some eagerness to get them feel part of the work – hoping this would best ensure their buy-in. So they came in to do what they knew best – prepare the land as if they were going to plant crops like maize and cassava.

September 16, 2019 6:44 pm

Am interested in mangrove restoration ecology. Am based at Kwale county, Kenya and I wish to learn more based on your project monitoring and evaluation