US Highway 14 drops into the town of Coon Valley after passing through Viroqua and Westby in the scenic landscape of the Driftless Area, a unique pocket of American geology, 85% of which is in western Wisconsin. The repeated pulses of the ice ages that pushed continental ice sheets across most of nearby North America never reached the Driftless. It’s an old landscape, incised by creeks and small rivers that wind their way eventually into the Mississippi between long ridges and steep slopes. The convoluted topography doesn’t lend itself to the giant flat farms of corn and soybeans that hem in the Driftless on several sides. Its geological legacy created an ecological and cultural legacy, reflected in everything from its history as a hotspot of Norwegian immigration to a recent renaissance in a back-to-the-land lifestyle and farm-to-table cuisine.

My trip to the Coon Valley corner of the Driftless was inspired by its role in the history of conservation. This was another episode in my visits to places where Aldo Leopold had conducted his pioneering ecological experiments in his lifelong career of trying to restore a sustainable and ethical relationship between humans and nature. Only two days earlier I had learned about his legacy at the University of Wisconsin Arboretum in Madison. At the same time that he was helping to found that laboratory for the scientific study of ecological restoration, he was also working in Coon Valley to apply some of those ideas in a practical, watershed-scale demonstration project.

Just before the road levelled out in the valley we turned into the driveway of an old farm, where Jon Lee was waiting for us. I’d been introduced to Jon, virtually, by a friend and professional contact who knew he would be able to give us a deep and personal introduction to the Coon Valley experiment and Leopold’s role in it. When we arrived, Jon had already spread out some historic photos of Coon Valley in the gazebo next to the driveway. He was tall and muscular, with close-cropped hair and blue eyes, in his mid-40s I guessed. I imagined he must have been the star of the Coon Valley football team back in his day. There was an instant rapport because of our mutual interest in the history of the farm, the town, and the Coon Valley Project. Jon’s grandfather, Adolf Lee, was one of the first farmers in the area to join the Project. According to Jon, Aldo Leopold visited Coon Valley to scope out the potential for working with local farmers, and quickly hit it off with his grandfather because of a shared passion for hunting and fishing. As part of the agreement with the project, a tree nursery was established on the Lee farm, below the barn and beside the cemetery of the Lutheran Church. Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers assigned to the project tended the seedlings.

Historic photo of tree nursery on the Lee Farm — note the treeless pasture above the house and barn. Photo courtesy of USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and Jon Lee.

Coon Valley? I’m sure almost no one nowadays has heard of it or knows that this was a pioneering experiment in “integrated conservation and development” and “collaborative conservation,” more than half a century before those terms had come into common use. Leopold, then based at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, worked with colleagues in the university’s College of Agriculture to persuade Hugh H. Bennett, chief of the new U.S. Soil Conservation Service, to establish the first national demonstration area for erosion control in the Coon Valley watershed. The Coon Valley Project, which began in 1933, was a cooperative effort among government technicians, university scientists, and local farmers. Leopold was an advisor to the project, and an involved, passionate proponent, who spent a lot of time talking to Coon Valley farmers, often from his informal “office” in the local restaurant and tavern. Eventually more than 400 farms, covering around 40,000 acres, were incorporated into the restoration efforts – the first such watershed-scale restoration effort in the United States.

Historic photo of erosion in Coon Valley. Photo courtesy of USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service.

With me on this visit to Coon Valley were friends who own a farm on a ridge in near Ferryville, Wisconsin, also in the Driftless Area, an hour’s drive south. They are implementing many conservation practices on their farm that are similar to those with roots in the Coon Valley Project. They grow some corn and soybeans, planted on contour and with minimum tillage, and raise a few beef cattle. They have an agreement with the State of Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to maintain natural forest on the steep slopes that drop into valleys to the north and south, and a conservation easement with the non-profit Mississippi Valley Conservancy. As part of the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service’s conservation reserve program, they have started to restore part of the farm to native prairie and have planted thousands of American hazelnut (Corylus americana), ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius), and wild plum (Prunus Americana), plants that provide food for wildlife.

——-

Leopold wrote about the Coon Valley experiment in an article in American Forests in 1935 titled “Coon Valley: An Adventure in Cooperative Conservation.” He described the project as follows: “Hence, after selecting certain demonstration areas on which to concentrate its work, it offered to each farmer on each area the cooperation of the government in installing on his farm a reorganized system of land-use, in which not only soil conservation and agriculture, but also forestry, game, fish, fur, flood-control, scenery, songbirds, or any other pertinent interest were to be duly integrated. It will probably take another decade before the public appreciates either the novelty of such an attitude by a bureau, or the courage needed to undertake so complex and difficult a task.” Maybe Leopold should have said “a century,” rather than a decade. As I opined in my previous essay about ecological restoration efforts at the University of Wisconsin Arboretum, our current public understanding and public policies are still lagging behind his vision from the 1930s.

In that 1935 essay, Leopold explained the history and cause of the problem that led to the need for the project: “When the cows which make the butter were first turned out upon the hills which comprise the scenery, everything was all right because there were more hills than cows, and because the soil still retained the humus which the wilderness vegetation through the centuries had built up. The trout streams ran clear, deep, narrow, and full. They seldom overflowed. This is proven by the fact that the first settlers stacked their hay on the creekbanks, a procedure now quite unthinkable. The deep loam of even the steepest fields and pastures showed never a gully, being able to take on any rain as it came, and turn it either upward into crops, or downward into perennial springs. It was a land to please everyone, be he an empire-builder or a poet. But pastoral poems had no place in the competitive industrialization of pre-war America, least of all in Coon Valley with its thrifty and ambitious Norse farmers. More cows, more silos to feed them, then machines to milk them, and then more pasture to graze them-this is the epic cycle which tells in one sentence the history of the modern Wisconsin dairy farm. More pasture was obtainable only on the steep upper slopes, which were timber to begin with, and should have remained so. But pasture they now are, and gone is the humus of the old prairie which until recently enabled the upland ridges to take on the rains as they came.”

Should I apologize for quoting these long paragraphs from Leopold, instead of summarizing their main points in a quarter as many sentences? I can’t bring myself to do that, because I love his clean, straightforward, old-fashioned, midwestern style so much, and wish I could get my own writing anywhere near that high orbit. So if it is too much, please just skim or skip ahead to the track of the narrative, and forgive me.

Historic photo of erosion in Coon Valley. Photo courtesy of USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and Jon Lee.

Leopold’s ecological mind immediately leapt from the gullies he observed in Coon Valley to the “big picture,” the interconnections, the “everything is connected to everything else” perspective. He wrote: “Result: Every rain pours off the ridges as from a roof. The ravines of the grazed slopes are the gutters. In their pastured condition they cannot resist the abrasion of the silt-laden torrents. Great gashing gullies are torn out of the hillside. Each gully dumps its load of hillside rocks upon the fields of the creek bottom, and its muddy waters into the already swollen streams. Coon Valley, in short, is one of the thousand farm communities which, through the abuse of its originally rich soil, has not only filled the national dinner pail, but has created the Mississippi flood problem, the navigation problem, the overproduction problem, and the problem of its own future continuity.”

Blind Lemon Jefferson, one of the most popular blues singers of the 1920s and ‘30s, wrote a song about the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 called “Rising High Water Blues.” That was the most destructive flood in the history of the United States. Twenty-seven-thousand square miles of land were flooded up to a depth of 30 feet, and almost a quarter-million African Americans in the Delta were displaced, leading many to migrate to northern cities. Some of the lyrics:

Backwater rising, Southern peoples can’t make no time

I said, backwater rising, Southern peoples can’t make no time

And I can’t get no hearing from that Memphis girl of mine!

By the time Leopold and Soil Conservation Service were working with the Norwegian farmers in Coon Valley to mitigate the damage already done in the watersheds of the Mississippi, African Americans were still streaming out of the states affected by the 1927 flood into northern cities in response to this eco-political crisis, changing the racial demography of the country forever.

——-

While we were talking in Jon Lee’s gazebo, Sam Skemp, the District Conservationist of the Natural Resources Conservation Service office in Viroqua, drove into the driveway to drop off some more historical photos of the Coon Valley Project. His office, the modern incarnation of the Soil Conservation Service that ran the Coon Valley Project in Leopold’s day, has a trove of historic photos, some of which Jon, a photographer as well as a farmer, has helped to restore and archive.

Jon was enthusiastic and animated. For him, this was family history, and he was proud of it. “I could go on for hours,” he said several times, and we knew he wasn’t kidding. At a natural break in the conversation, I took the opportunity to walk down across the field below the farmhouse and barn to try to find the exact spot to repeat one of the historic photos Jon had shared with us, of the CCC tree nursery, the farm, and the hills in the background. I hopped over a low electric fence and walked down to a fence corner beside the Lutheran Cemetery. By matching angles between farm buildings, I found the exact spot for a repeat photo. The bare slope above the house and barn in the photo from the 1930s, with only two lonely oaks then still standing in the deforested pasture, was now invisible under a dense, restored forest.

Jon offered to take us on a little local driving tour to find some other sites of the historic photos, both on the Lee Farm and some neighboring farms. He pointed out the site where, in a photo from the project days, bundles of branches are being laid in a gullied stream on the Lee Farm. Today, the gully had mostly filled in and the stream level had risen to nearly that of the old banks.

Historic photo showing erosion control measures on the Lee Farm. Photo courtesy of USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and Jon Lee.

Repeat photo of the creek where erosion control measures were implemented on the Lee Farm, 22 June 2018.

A little farther upstream he led us to the edge of a wooded slope where we tasted the clear cold water coming from a small spring, drinking from a long-handled metal dipper. Before the Coon Valley Project, the slope above the spring had probably been cleared as dairy pasture, the spring probably dried up or undrinkable.

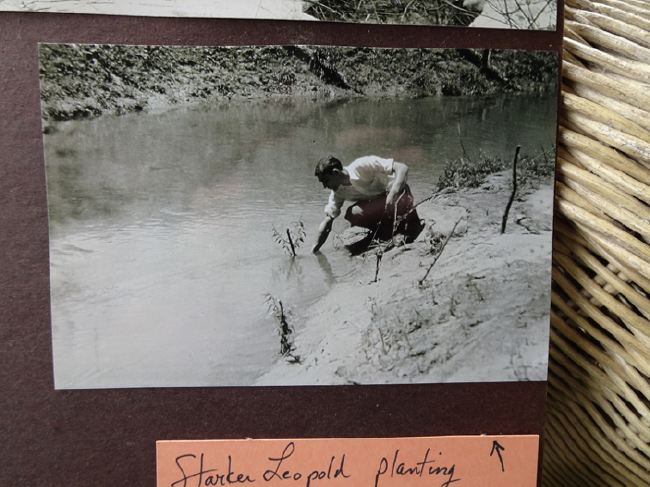

We also went to the neighboring Neprud Farm, where a historic photo of Aldo’s son, Starker Leopold, planting willows had been taken. That photo reminded me of something else Leopold wrote in “An Adventure in Cooperative Conservation,” which echoed his later essay about the Arboretum: “Science doesn’t know the answer.” That truth, still mostly true today, justifies the precautionary principle and approach to environmental management and conservation. In his essay on Coon Valley, Leopold wrote that “The bank plantings have showed up a curious hiatus in our silvicultural knowledge. We have learned so much about the growth of the noble conifers that we employ higher mathematics to express the profundity of our information, but at Coon Valley there have arisen, unanswered, such sobering elementary questions as this: What species of willow grow from cuttings? When and how are cuttings made, stored, and planted? Under what conditions will sprouting willow logs take root? What shrubs combine thorns, shade tolerance, grazing resistance, capacity to grow from cuttings, and the production of fruits edible by wild life? What are the comparative soilbinding properties of various shrub and tree roots?”

Historic photo of Starker Leopold planting willows. Photo courtesy of USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and Jon Lee.

——-

In the Preface to The Driftless Reader, a collection of Driftless lore edited by Curt Meine and Keefe Keeley, published by the University of Wisconsin Press in 2017, the editors gave what is for me a nice synopsis of the place: “The Driftless Area has also been an important laboratory for working out the relationship between humans and the land. It is neither “pristine” nor wholly humanized. It holds within it the wild and the cultivated. The Driftless is not unique in displaying such tensions. They can and do arise any place that people inhabit. Yet the confluence of nature and culture in the Driftless is unique, the channels of ecological and social change still shaping the hills.”

Meine, and the southwestern conservationist and writer Gary Nabhan, reflected on Coon Valley in an insightful short essay “The Coon Valley “Cooperative Conservation” Initiative, 1934.,” placing it as one of the earliest examples of community-based conservation in the U.S. They wrote: “Although intense flood events, urban encroachment, and current high prices for corn and soy today pose threats to the watershed’s land stewardship legacy, Coon Valley has amply demonstrated that “cooperative conservation” can indeed work over the long haul for the local economy, for the maintenance of the rural cultural community, and for the resilience of the biotic community. The Coon Valley watershed continues to attract attention from scientists and land stewardship advocates. … The Coon Valley experience suggests that, over time, community- based collaborative conservation can enhance ecosystem services, economic productivity, and social cohesion in a landscape. … It is the internalization of a land ethic among local land stewards and food producers that accounts for the persistence and successes of the Coon Valley Watershed Project over eight decades.”

In Coon Valley, not only on the Lee Farm and my friends’ farm near Ferryville, that “internalization of a land ethic” seemed apparent. The legacy of integrating conservation and development is creating something of a green economic renaissance in the area. Organic Valley, a large national producer and distributor of organic dairy products, is a Driftless success story. Jon and his wife are raising grass-fed beef on the farm, and he said the local marketing network can take all he can raise. After saying goodbye to Jon, we stopped for lunch at the Driftless Cafe in Viroqua. Although it was well past the traditional lunch hour, the place was bustling. We got a table in the back room and ordered cheeseburgers of grass-fed local beef topped with local cheese and local organic everything else. It was delicious. Conserving nature and the human-nature relationship has a flavor – a unique flavor in every place, depending on its ecological and cultural evolutionary history, the flavor of “everything connected to everything else.” I could taste it here.

For related stories see:

- A Morning at the University of Wisconsin Arboretum in Madison. June 2018.

- Delta Blues: How to Walk on the Shifting Ground Beneath Our Feet. December 2016.

- A Morning Visit with Aldo Leopold at the Shack. August 2016.

- Not Nature Apart Either: A Case Study of Point Reyes National Seashore and the Drakes Bay Oyster Company. August 2014.

Sources and related links:

- Driftless Area

- Cities with the Highest Percentage of Norwegians in Wisconsin

- Coon Valley, Wisconsin: A Conservation Success Story. Douglas Helms, 1992.

- Coon Valley Days: A short history of the Coon Creek Watershed Demonstration Project. Renee Anderson, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2002.

- Aldo Leopold and the Coon Valley watershed conservation project. Caroline Schneider. 2013. Soil Science Society of America.

- Mississippi Valley Conservancy

- The River of the Mother of God and Other Essays by Aldo Leopold. Edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 1991. U. of Wisconsin Press.

- “Rising High Water Blues.” Blind Lemon Jefferson.

- The Driftless Reader. 2017. Curt Meine and Keefe Keeley, Eds. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Curt Meine and Gary P. Nabhan. 2014. Historic Precedents to Collaborative Conservation in Working Landscapes: The Coon Valley “Cooperative Conservation” Initiative, 1934. In Stitching the West Back Together: Conservation of Working Landscapes. of Chicago Press.

- Driftless Café, Viroqua, Wisconsin

August 2, 2018 12:18 pm

Highly informative, entertaining, and instructive about commitment, time required, and the limits of knowledge for how restoration ecology or an ICDP approach will play out. Thanks.

August 30, 2018 2:39 pm

Thanks, Michael. Your comment is especially appreciated, given your own deep experience with and knowledge of the challenges of community-based, “cooperative” and “collaborative” conservation and natural resources management!

August 10, 2019 7:51 pm

Thanks. I am planning my own Leopold pilgrimage next month. I may drop by Coon Valley. Your note is very informative.