December 2016. It was a sunny late morning on a cool December day when we arrived at the Oakley Plantation in south-central Louisiana near St. Francisville, about two hours on fast highways from New Orleans. It would have been a slower trip for John James Audubon, who arrived here on June 18th, 1821. He’d met the lady of the plantation, Lucretia “Lucy” Pirrie, in New Orleans some months earlier, and she had invited him to Oakley to tutor her 16-year-old daughter Eliza in art, music, math, and etiquette.

The Oakley Plantation is in an area of Louisiana known as West Feliciana Parish, which in the decades before Audubon arrived had been caught up in the geopolitical tides of the times. In 1763, after the Seven Years War, France ceded this part of its New World territories to Great Britain as the province of West Florida. But Spain gained control of the area during the American Revolutionary War, and maintained control for three decades. In 1810, the landowners in the area, many of British descent, rebelled against Spanish rule and briefly declared the independent Republic of West Florida. Within a few months of this local rebellion, however, the United States declared the area to be part of the Louisiana Purchase, which had been concluded in 1803 during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson, and it became part of the new U.S. state of Louisiana.

Through all those political changes, a few land-owning families lived at an extraordinary level of wealth, equivalent to today’s billionaires, in a semi-feudal plantation economy based on the cheap labor of slaves, who produced commodities like sugar, cotton, and indigo for export. The level of inequality is almost unimaginable. In the plantation house, the white family – in this case James Pirrie and his wife Lucy and their two daughters – lived a life of luxury similar to that of the elite in Europe and the big cities of the U.S. at the time, enjoying the finest imported goods the world had to offer, although in a rural setting. The slaves’ lives were at least as bleak as those of the poorest feudal peasants in Europe a millennium earlier. About 300 slaves did the work at the Oakley Plantation, supporting the Pirrie family’s lifestyle with their labor. This was the setting Audubon stepped into in 1821, four decades before the outbreak of the Civil War.

For Audubon, then down and out and grasping for work, Lucy Pirrie’s offer was one he couldn’t refuse: tutor Eliza in the mornings for what was then a generous wage of $60 a month plus room and board, and in the afternoons he would be free to wander the nearby woods and swamps looking for birds to observe, shoot, and paint.

The time at Oakley Plantation was an extremely productive period for Audubon, in some ways the most intense and prolific period of his career, and it re-launched his life’s project of painting all American birds. From June to October 1821 he painted 32 of the 435 species that later appeared in Birds of America, one approximately every three days, more than at any other place or time. One of his most poignant bird portraits, a colorful, happy flock of Carolina Parakeets, was sketched at the Oakley Plantation. That once abundant and now extinct species, the only parrot indigenous to the United States, was last seen in the wild in 1910.

Audubon was a careful observer of bird behavior and often sketched his subjects in nature – before shooting and stuffing them so he could paint the details of their plumage in his studio. His bird portraits often show some aspects of the ecology of the subject species, such as its habitat or common food or prey. Because of that I think of Audubon’s paintings as some of the first truly ecological art.

He arrived at Oakley Plantation with his first apprentice and assistant, teenaged Joseph Mason, who painted the backgrounds for all of the birds Audubon painted there. Audubon’s dramatic portrait of the Great Egret dates to 1821, and was probably made at Oakley.

——-

It was a slow Thursday morning at the Audubon State Historic Site. Our tour guide seemed a little sleepy and bored at first, but she warmed up with our questions and proved to be very knowledgeable about Audubon’s history at the Oakley Plantation.

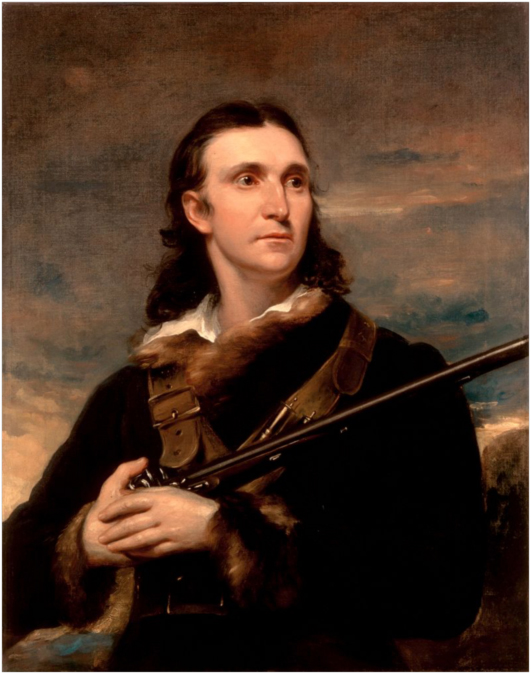

Louisiana claims Audubon as one of its famous citizens. Of the 435 birds in Birds of America, he began painting at least 167 of them in that state. He sometimes claimed to have been born on a Louisiana plantation, but he was lying. In fact, he was born in 1785 in what is now Haiti, then a colony of France, to a French sea captain and landowner and his young French mistress. Audubon’s father already had a family in France and a second Creole family in Haiti. When Audubon was very young and after his mother had died, with the Haitian slave revolt impending, his father took his illegitimate son to France for safety and adopted him into his French family. There, schooled in the upper-class culture of the day, John James learned languages, art, dancing, fencing, and music.

But in 1803 he was again caught up in the tides of history. His father feared that his son would be conscripted into Napoleon’s army, so he sent him to the young United States of America, where he owned a farm called Mill Grove, near Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, only about 20 miles west of Philadelphia. (I wrote about my visit to Audubon’s house at Mill Grove in July 2012.) John James Audubon arrived in New York at the age of 18, with papers prepared by his father stating that he had been born to French parents on a plantation in Louisiana, a ruse to cover up his illegitimate parentage.

In the Oakley Plantation’s second story living room a portrait of Lucy Pirrie, Audubon’s employer and patroness, showed her with a very stern expression – certainly not a woman to cross, from her look. Another portrait, painted by Audubon himself, was of her daughter Eliza. She looked young and confident, even a bit bold.

According to our tour guide, Audubon was dismissed as Eliza’s tutor – “run off,” were the words she used – by her mother after three and a half months.

“Really?” we asked. Yes, she said, Audubon was known to be arrogant and hard to get along with, and “He was run off many times, in other places.” There was some allusion to a romantic intrigue between Eliza’s older sister and a suitor she wanted to steer away from younger Eliza, but no insinuations that Audubon had a role in that drama – although he was said to be dashingly handsome according to some sources. At the time, he was married and had two sons, and from all accounts was devoted to his wife, Lucy Bakewell Audubon, whom he had met and married during his young days at Mill Grove, Pennsylvania.

——-

All of that piqued my interest, and I was skeptical of the characterization of Audubon given so confidently by our tour guide, so I turned to an excellent, relatively recent biography to learn more about him: Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America, by William Souder (2004). Audubon was a complicated man, and the complicated historical context of his life makes him a worthy subject for biographical scholarship – and romantic and philosophical mythologizing.

I hadn’t realized that Audubon had captured the imagination of two southern writers whose names I had heard before, but whose works I hadn’t read. One of those was Robert Penn Warren (1905-1989), who received the 1947 Pulitzer Prize for his 1946 novel All the King’s Men, and the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1958 and 1979 – the only person to have won Pulitzer Prizes for both fiction and poetry. All the King’s Men is based on the story of Huey P. Long, populist Governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932, and U.S. Senator from 1932 until he was assassinated in 1935. Warren taught at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge from 1933 to 1942. In his long poem, Audubon: A Vision, published in 1969, Warren makes Audubon a mythic hero – his life a heroic quest to paint all of the birds of America. Critics at the time saw this poem as a “watershed moment” in Warren’s own artistic career. Audubon’s quest must have somehow spoken to Warren’s own life project. In a review of Warren’s collected poems, Steven Ealy wrote: “For Warren, coming to terms with Audubon – whether the historical Audubon or Warren’s own mythic recreation of Audubon – is crucial in coming to terms with and understanding himself. In seeking the heart of Audubon, Warren was coming to understand his own heart. To walk in the world with passion (“what is man but his passion?” Warren asks early in the poem) is, finally, one way to establish one’s identity in the world.”

Literary analysts and critics have traced the influences on his poem to an earlier writer, Eudora Welty, and her short story “A Still Moment,” published in 1943. Eudora Welty (1909-2001) was herself a remarkable person, a writer of short stories and novels about the American South, and an accomplished photographer as well. Welty won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her novel The Optimist’s Daughter in 1973. A short passage from “A Still Moment” gives a flavor of her sparse, poetic style and her portrayal of Audubon as a mythic hero or archetype:

“Audubon in each act of life was aware of the mysterious origin he half-concealed and half-sought for. … But if it was his identity that he wished to discover, or if it was what a man had to seize beyond that, the way for him was by endless examination, by the care for every bird that flew in his path and every serpent that shone underfoot. Not one was enough; he looked deeper and deeper, on and on, as if for a particular beast or some legendary bird. Some men’s eyes persisted in looking outward when they opened to look inward, and to their delight, there outflung was the astonishing world under the sky. When a man at last brought himself to face some mirror-surface he still saw the world looking back at him, and if he continued to look, to look closer and closer, what then? The gaze that looks outward must be trained without rest, to be indomitable. … and then, Audubon dreamed, with his mind going to his pointed brush, it must see like this, and he tightened his hand on the trigger of the gun and pulled it, and his eyes went closed. In memory the heron was all its solitude, its total beauty. All its whiteness could be seen from all sides at once, its pure feathers were as if counted and known and their array one upon the other would never be lost.”

Perhaps Audubon’s tragic flaw, his all-too-human hubris, was to want to capture and fix forever the fleeting moments, the ephemeral beauty, of life. To escape from time. Winding down her story to a philosophical conclusion, Welty teases us with the speculation that our feeling of separateness from the world may be due to this human grasping, this tendency to attachment. “Perhaps God never counted the moments of Time,” she wrote; “Time did not occur to God.” It’s a very buddhist idea.

——-

A few days after visiting the Oakley Plantation we hiked the trails and boardwalks of the Barataria Preserve, a unit of the Jean Laffite National Historical Park and Preserve, only a 30-minute drive from the New Orleans French Quarter. We watched quietly as a Great Egret (Ardea alba) tiptoed along the opposite bank of an old canal built for logging the baldcypress of the swamp, hunting a late breakfast, maybe even brunch. It would stalk, freeze, and then with a lightning-fast jab of its yellow beak spear another morsel. Through binoculars I watched as it struggled to get a good hold of a squirming brown anole lizard, which after a few tries it did. The egret tossed it down and swallowed before resuming its deadly slow stalk.

It would have been in exactly that quiet instant, his prey distracted by its own intense focus, that the blast of Audubon’s gun beside me would have killed it, to be taken back to his studio to be studied and painted. The spreading red stain of its blood on the immaculate white feathers would have been washed off and its snowy plumage immortalized with his timeless white pigments.

After watching the feeding egret for a long time, we walked slowly back to the trailhead, savoring the ephemeral moment, silently celebrating what Eudora Welty brilliantly called this “astonishing world under the sky.”

For related stories see:

- The Art of Ecology: Audubon’s Oystercatchers and Other Examples. November 2014.

- Visiting Revolutionary Ecological Relatives in Philadelphia. July 2012.

Sources and related links:

- Oakley Plantation House

- Audubon in Louisiana

- Portrait of John James Audubon. 1826. By John Syme, Edinburgh, Scotland.

- John J. Audubon’s Birds of America

- Audubon’s Aviary, New-York Historical Society

- Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), study for the Birds of America, circa 1825

- Carolina Parakeet was painted at Oakley House

- Great Egret (Ardea alba), New-York Historical Society

- Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America, by William Souder, 2004. Milkweed Editions.

- Audubon: A Vision. 1969.

- Steven Ealy. 2000. Quest for a Story of Deep Delight: Robert Penn Warren’s Poetic Genius.

- Of Herons, Hags and History: Rethinking Robert Penn Warren’s “Audubon: A Vision” 1994. Daniel Duane. The Southern Literary Journal 27, No. 1 (Fall, 1994), pp. 25-35.

- Eudora Welty

- A Still Moment. Eudora Welty.

- Barataria Preserve, Louisiana

February 17, 2017 12:20 am

Another great story Bruce!

February 18, 2017 9:50 pm

Harold, I’m glad you enjoyed this one too, and thanks for the positive feedback! Bruce