November 13th, 2016. Exactly four years ago I wandered around The Nature Conservancy’s Nags Head Woods Ecological Preserve, and what I saw triggered a cascade of ideas that I described in a story posted then called “Pondering the Ponds of Nags Head Woods.” When I visited in 2012, Hurricane Sandy had brushed by the Outer Banks two weeks earlier, and Barack Obama had been re-elected a week after that. This year the wrathful winds, rains, and waves of Hurricane Matthew had paid a visit a month ago. I’ve been walking the gentle trails of the Nags Head Woods Preserve every year since 2010, but this year I was especially curious to see if I could see any evidence of this storm in the ponds or forests of the preserve.

Nags Head Woods cover old, now-stabilized dunes, and the topography creates dozens of depressions of varying sizes that collect water, forming ponds among the loblolly, magnolia, sassafras, sweetgum, oak, hickory, holly, and blackgum. Because of its complex topography and biogeographical history this small 1,100 acre remnant of Atlantic maritime forest harbors more than 550 species of plants. The Nature Conservancy has been protecting it, and incorporating more land when possible, since 1978.

Part of the reason for my renewed “pondering” this year was that in 2012 my visit made me think hard about the concept of ecological “resilience,” and it was on my mind again. Resilience describes the ability of ecosystems to remain stable after events or “shocks” that stress and alter the normal conditions to which they are adapted. The term was first used by the Canadian ecologist C.S. Holling in a 1973 paper to describe the relative stability and persistence of ecosystems despite disturbances from natural or human causes. Ecosystems aren’t always resilient, and sometimes surprisingly large shifts can occur. Sometimes ecosystems “flip” from one condition and structure to something so different it seems unbelievable. From a forest to a grassland, for example, or from a coastal kelp “forest” to a coast with no kelp. Research has shown that in a given place very different ecosystems can exist as alternative stable states, and that disturbances, if they are large enough to cross some threshold, may flip the ecosystem from one state to another. Resilience has been defined in the ecological literature as “the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks” – in other words, the ability to resist major ecological regime shifts.

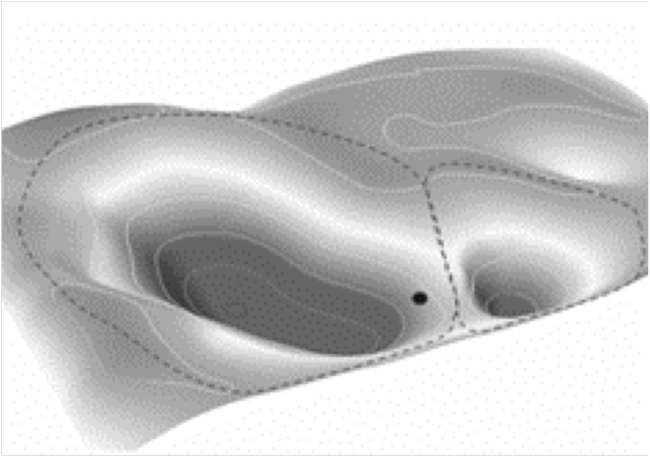

Some ecologists have used a visual analogy, which they call a “stability landscape,” to represent the possibility of alternative stable states. Depressions in the surface of such a hypothetical “landscape” represent those alternative states. If some disturbance could “bump” the system over a divide or hump between depressions, it might fall into a neighboring hole and be stuck there until another disturbance came along that could bump it into another stable state. That possibility is what the stability landscape is supposed to map.

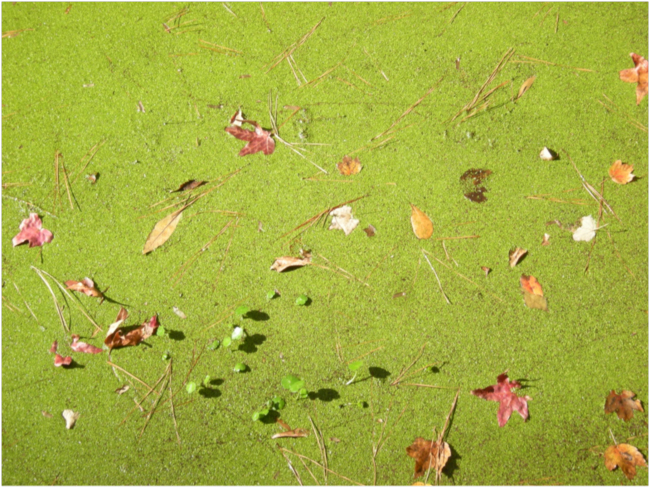

This somewhat surreal “stability landscape” image made me think of a fine-scale topographic map of Nags Head Woods, with the depressions between the ancient dunes filled now with ponds. In that blog of four years ago, I drew on the concept of ecological resilience as I pondered why some ponds in Nags Head Woods were completely covered in duckweed (Lemna spp.) – tiny floating plants that made them look like a green lawn – while others were completely free of duckweed, blackwater mirrors reflecting the sky and their shorelines. There were green ponds and black ponds, but there didn’t seem to be many in-between ponds. Duckweed or no duckweed appeared to be alternative stable states. How often does a green pond flip to a black pond, or vice versa, I wondered? In 2012 I argued that having an ecological preserve like Nags Head Woods that encompassed such situations was an important scientific resource for trying to investigate the question of why these two states of ecological being can exist side by side, and what subtle factors create one or the other.

——-

Eight miles of trails wind through these woods, and on the Roanoke Trail a big loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) had been a victim of Matthew’s winds. It had been sawed through to reopen the trail, and the trunk here, about a foot in diameter, had 40 annual growth rings. I guessed that we were about halfway up the old tree, so I estimated that it must have been 80 or more years old. That would mean it was a youngster when the last of the Tillet family were still living on a farm here in the 1930s. They abandoned the place in the 1940s, and the woods have grown up over the old fields. Apparently this Atlantic maritime forest is fairly resilient in an ecological sense.

My quick, observational report on the changes in the ponds of Nags Head Woods over four years: It looked to me like Hurricane Matthew’s heavy rains, which flooded large areas of Nags Head and its sister towns of Kitty Hawk, Kill Devil Hills, and Manteo, had raised the level of the ponds by a few feet. Besides the toppled loblolly pine, a big blackgum had fallen across a pond along one of the trails. But otherwise there was not really much evidence of the recent hurricane. The duckweed-covered ponds are still duckweed-covered, and the blackwater-mirror ponds are still blackwater mirrors. The rains didn’t change the underlying ecological conditions of the ponds, it seemed. They were, in ecological terms, resilient to this passing climatic perturbation.

What struck me as interesting and puzzling this time – it hadn’t in 2012 – was the “polarization.” The dichotomous, green or black, states of these ponds. The very raw, recent presidential election made me sensitive to that interpretation, I guess. But how can ponds be polarized partisans?

Resilience theorists are now applying the concept to what they call “social-ecological systems.” Besides wanting to state that social systems are always connected to ecosystems and vice versa, another part of their intent in using this label is to call attention to the fact that social systems, like ecosystems, may be resilient – or not. The “social” part of social-ecological systems are sensitive to social, economic, and political “disturbances,” and may “flip” from one alternative state to a very different one suddenly, if some previously unknown threshold is crossed. Social systems also exist in a “stability landscape,” and certain disturbances may bump them from one condition to something quite different.

Driving through the neighborhood from the main north-south “drag” – US Highway 158 – that runs through the Nags Head section of the Outer Banks to the Nags Head Woods Preserve, I was saddened, but not really surprised, to see an American flag flying upside-down, with a Confederate battle flag below it, on a flagpole in the front yard of a house. Four days after the presidential election, I could guess which candidate this resident voted for.

The ascendency of an anti-science, anti-environmental, climate-change denier to the presidency is an unexpected shock to which the social-ecological system of the Outer Banks, not to mention the United States and the planet, may or may not be resilient. Hurricane Donald has struck, and we are still waiting to access the damage.

The flag that probably should be flying upside down after this election, in an ecological “mayday” call, is the old “ecology flag,” a now mostly forgotten symbol from the 1970s, the early days of the environmental movement. Back then it was some people’s version of the Confederate battle flag, a call to arms on behalf of Planet Earth.

There’s a rumor circulating that President Trump will buy the Nags Head Woods Preserve from The Nature Conservancy, whether they want to sell it or not. Maybe it will be taken through a new presidential version of “eminent domain” to benefit a “higher use” (i.e., the Trump Organization). It will be converted into a new golf resort. Those ponds? They will make nice water hazards – not all, of course, most will have to be filled. The duckweed will have to go, of course – nothing a little herbicide can’t take care of. And of course the trees will mostly have to go, to make room for the fairways and neighborhood of upscale homes. A few trees will be left. It will, after all, be called Trump’s Woods.

No, just joking! Or maybe not…

For related stories see:

- Pondering the Ponds of Nags Head Woods. November 2012.

- Outer Banks Encounters. November 2013.

- The Meaning of Human Existence: A Continuing Conversation with E.O. Wilson. April 2015.

- Pondering the Palms of Cape Hatteras. November 2015.

Sources and related links:

- The Nature Conservancy Nags Head Woods Ecological Preserve

- Walker, B., C. S. Holling, S. R. Carpenter, and A. Kinzig. 2004. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society 9(2): 5

- Nags Head Golf Links