I’ve been thinking a lot lately about Robinson Jeffers, a Californian poet who was widely known and read beginning in the 1920s, through the 1930s and 40s, and into perhaps the 1970s in some, especially environmentalist, circles.1 Jeffers was on the cover of Time magazine on April 4, 1932, unusual notoriety for a poet. In 1941, he was invited to Washington, DC, by the Library of Congress to give the inaugural address at a conference called “The Poet in a Democracy.”

At the end of my “book tour” to California in September and October, talking about and promoting my book Nature on the Edge: Lessons for the Biosphere from the California Coast, I spent a few days in Carmel-by-the-Sea, where Jeffers lived and worked most of his life. After the trip I wrote to a friend who knows a lot about Jeffers and the Big Sur: “I think I’m going to put together some sort of little essay or blog about Jeffers’s worldview and what I’ve been thinking and feeling lately. I’m on a sort of Jeffers jag, I guess.” Andrew egged me on, writing “A Jeffers jag is a fine thing.”

https://poets.org/poet/robinson-jeffers

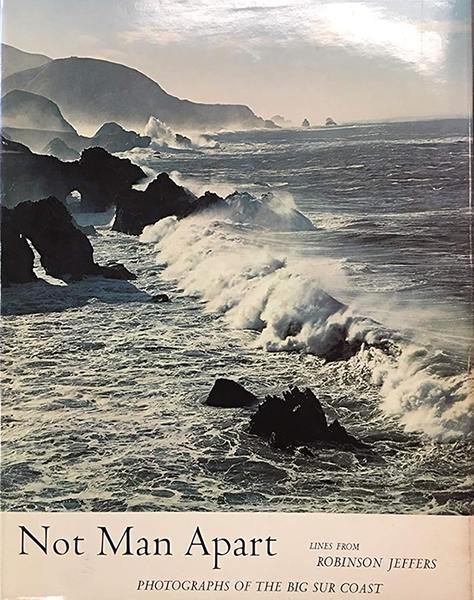

Well, I suppose, but it is a lot of work! Robinson Jeffers (1887-1962) was a prolific and profound poet whose life spanned vast changes in America and the world, from the troubled late 1800s to the troubled 1960s—roughly the generation of my grandparents. (His life had an especially close overlap in age and era with my maternal grandfather, Harry Sweeney (1888-1960)). He saw two world wars, a great economic depression, the invention of nuclear weapons, and the first decades of the Cold War. Through it all he had a unique and profound ability to situate himself deep in human history and beyond, in psychological, evolutionary, geological, and cosmological history. And a unique talent, as a poet, to find words to reflect or at least hint at that perspective. No wonder he became a voice for the environmental movement that accelerated and solidified beginning in the 1960s. His three words, “not man apart,” taken from his 1936 poem “The Answer,” became the title of the Sierra Club’s large format book of photographs of the Big Sur Coast and excerpts from Jeffers’s poetry, Not Man Apart, published in 1969, the year I started college.

About that time, David Brower left the Sierra Club to found Friends of the Earth, and “Not Man Apart” became the title of the FOE newsletter, which I read faithfully for many years. The point of view—or the worldview, really—suggested by the phrase “not man apart” resonated with me as soon as I heard it. My Jeffers “jag” is an old thing, I guess. In August, 2014, I explored my connection with Jeffers in an essay, “Not Man Apart: Genealogy of an Ecological Worldview”.

Carmel was where Jeffers lived for most of his life, with his wife Una, at “Tor House,” a cottage hand-built from wave-worn granite boulders hauled up from the beach below the bluff on which it perched. As described in the essay linked above, I toured Tor House and its “Hawk Tower” in 2014.

On this trip I would not be in Carmel on a weekend, when Tor House tours happen, but serendipitously my short stay there coincided with a lecture titled “The Poet in a Democracy: Robinson Jeffers and His Relevance Today,” by Elliot Ruchowitz-Roberts, president of the Robinson Jeffers Tor House Foundation. We squeezed into folding chairs in the packed room with the mostly older, affluent members of the Carmel community; we suspected that most here were drawn, in part, by their concern for democracy in the present era, and were wondering what wisdom Jeffers might offer. The talk was excellent, blending Jeffers’s words with a historical chronology of his struggle with the dark and depressing global developments including World War I, World War II, and the development of nuclear weapons. The aura of those times has, to me, an eerie similarity to the dark and depressing present moment. I too wanted to hear about Jeffers’s “relevance today,” to his thoughts about how to live in these times. The talk reconnected me with his verse and philosophy, and set me off on my “Jeffers jag,” a renewed conversation with this prophetic poet. Drives and hikes down the Big Sur coast added images and perspectives to my ponderings, and a balm of beauty.

Living in a Dark Time

This morning Hitler spoke in Danzig, we heard his voice.

A man of genius: that is, of amazing

Ability, courage, devotion, cored on a sick child’s soul,

Heard clearly through the dog-wrath, a sick child

Wailing in Danzig; invoking destruction and wailing at it.

So began Jeffers’s “breaking news” poem titled “The Day is a Poem (September 19, 1939)”

Today, every day now, our president speaks in Washington, or on Air Force One, or from Mar-a-Lago. Every day now, many times a day, at all hours of day or night, he sends messages on “Truth Social”, and I read about them the next morning in the Washington Post. Every day is a poem. He is a man of genius, with the soul of a sick child.

Jeffers’s “The Day is a Poem” continued:

Well: the day is a poem: but too much

Like one of Jeffers’s, crusted with blood and barbaric omens,

Painful to excess, inhuman as a hawk’s cry.

We are again living in a dark time, a cusp of human and evolutionary history—as Jeffers was, and knew he was, when he wrote this poem at the beginning of World War II. In the last two decades of his life, after World War II, and into the nuclear Cold War era (he died in 1962 at 75), he was writing some of his most critical and philosophical poetry. Looking back over his lifetime, with his knowledge of Western history and philosophy, he clearly saw that things were not getting “better,” that human societies were not making “progress” in their interactions with the planet and with each other, and hadn’t been for his whole life.

In his narrative poems Dear Judas and Medea, Jeffers criticized all of Western and Christian history and values. But, writes James Karmen in his biography of Jeffers, Robinson Jeffers: Poet and Prophet,

If, in the Western tradition or in American culture, any pillars of belief were left standing after these assaults, Jeffers struck them down with The Double Axe and Other Poems, published in July 1948. His attack was so ferocious and so far-reaching that Random House famously (or notoriously) issued a disclaimer with the book, stating in a “Publishers’ Note” that “Random House feels compelled to go on record with its disagreement over some of the political views pronounced by the poet in this volume.”

Jeffers challenged the fundamental myths of the American culture of the day, and its guardians reacted strongly. He saw the role of the poet in a democracy as speaking truth to power, to use a Quaker phrase. He identified himself with Cassandra, the prophetess of Greek mythology, who always accurately forecast the future but was fated never to be believed. “Truly men hate the truth; they’d liefer / Meet a tiger on the road,” he wrote in his poem “Cassandra,” from The Double Axe. The poem concludes with the lines “No: you’ll still mumble in a corner a crust of truth to men / and gods disgusting. – You and I, Cassandra.”

In his poem “A Redeemer,” from Cawdor and Other Poems (1928), Jeffers excoriated Euro-American history and the myth of “Manifest Destiny,” which was its foundation:

They have done what never was done before. Not as a people takes a land

to love it and be fed,

A little, according to need and love, and again a little; sparing the country

tribes, mixing.

Their blood with theirs, their minds with all the rocks and rivers, their flesh

with the soil: no, without hunger

Wasting the world and your own labor, without love possessing, not even

your hands to the dirt but plows

like blades of knives; heartless machines; houses of steel: using and

despising the patient earth …

Oh as a rich man eats a forest for profit and a field for vanity, so you came

west and raped

The continent and brushed its people to death. Without need, the weak

skirmishing hunters, and without mercy.

He asks, in that poem, “when I am dead and all you with whole hands / think of nothing but happiness, / Will you go mad and kill each other? Or horror come over the ocean on / wings and cover your sun?”

I read those lines as a premonition of nuclear war, and “cover your sun” the darkness of “nuclear winter,” a scenario that was not discovered by climate modelers until the late 1970. His prophetic poetic premonition gives me goosebumps.

Hummingbird Trumpet (Epilobium canum) (foreground)

How Should We Think About It?

If we are again living in a dark time, as Jeffers felt he was, how should we think about it? In “The Inhumanist,” Part II of The Double Axe (1948), Jeffers wrote:

… there is not an atom in all the universes

But feels every other atom; gravitation, electromagnetism, light, heat, and

the other

Flamings, the nerves in the night’s black flesh, flow them together; the stars,

the winds and the people: one energy,

One existence, one music, one organism, one life, one God: star-fire and

rock-strength, the sea’s cold flow

And man’s dark soul”

This passage, like much of his writing, presents a view of everything interconnected and interdependent, a holistic, systems worldview. James Karman, writing in the introduction to Stones of the Sur, a compilation of poetry by Jeffers and photographs by Morley Baer (Stanford University Press, 2001), says: “To truly live, Jeffers concluded, one must break through human self-centeredness, which encourages people to believe they are the raison d’etre of the universe, and bow before the ‘transhuman magnificence’ of the larger world. The reward for those who do so, as Jeffers declares in a speech by Orestes near the close of The Tower Beyond Tragedy, is a transcendent experience of oneness and unity.” In the speech Karman refers to, Orestes says:

I entered the life of the brown forest

And the great life of the ancient peaks, the patience of stone,

I felt the changes in the veins

In the throat of the mountain, a grain in many centuries, we have

our own time, not yours; and I was the stream

Draining the mountain wood; and I the stag drinking; and I was

the stars

Boiling with light, wandering alone, each one the lord of his own

summit; and I was the darkness

Outside the stars, I included them, they were a part of me, I was

mankind also, a moving lichen

On the cheek of the round stone … they have not made words

for it, to go behind things, beyond hours and ages,

And be all things in all time, in their returns and passages, in the

motionless and timeless center,

In the white of the fire …

Jeffers was certainly familiar with the naturalistic philosophy and ethics of the Greek Stoics. He probably also was familiar with the thought of Emmanuel Swedenborg, the controversial Swedish scientist and mystic, who had studied crystal formation, and who argued that the seemingly automatic, self-organizing patterns generated in crystallization reflected a deeper connection and pattern in nature. Swedenborg used an analogy from the Stoics, writing that nature was like a spiderweb: “For it consists, as it were of infinite radii proceeding from a center, and of infinite circles or polygons, such that nothing can happen in one which is not instantly known at the centre, and thus spreads through much of the web. Thus through contiguity and connection does nature play her part.” The Concord Transcendentalists, Emerson and Thoreau for example, were familiar with this metaphor, and Jeffers also knew their philosophy well.

In 1934 (remember he had already been on the cover of Time by then), Jeffers responded to a question about his “religious attitudes” from Sister Mary James Power. a principal and teacher at a girls’ Catholic high school in Massachusetts. A lifelong lover of poetry, she had contacted a list of the leading poets of the day, including Jeffers, and invited their reflections on the spiritual dimensions of their work. His response, originally published in Powers’s 1938 book Poets at Prayer and later included in Albert Gelpi’s The Wild God of the World: An Anthology of Robinson Jeffers, “is one of the most beautiful and succinct articulations of a holistic, humanistic moral philosophy ever committed to words — some of the wisest words to live and think and feel by.”2

I believe that the universe is one being, all its parts are different expressions of the same energy, and they are all in communication with each other, influencing each other, therefore parts of one organic whole. (This is physics, I believe, as well as religion.) The parts change and pass, or die, people and races and rocks and stars, none of them seems to me important in itself, but only the whole. This whole is in all its parts so beautiful, and is felt by me to be so intensely in earnest, that I am compelled to love it, and to think of it as divine. It seems to me that this whole alone is worthy of the deeper sort of love; and that here is peace, freedom, I might say a kind of salvation, in turning one’s affection outward toward this one God, rather than inward on one’s self, or on humanity, or on human imagination and abstractions …

When Thoreau wrote that humans need to “realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations,” I imagine he had this kind of idea in mind; maybe Jeffers was echoing or channeling Thoreau when he wrote this.

The Stoic-Swedenborgian spiderweb is similar to the Buddhist image of the “Net of Indra” described in the Avatamsaka Sutra. The “Jewel Net of Indra” is pictured as stretching infinitely in all directions, and at each of the knots or nodes of the net there is a glittering jewel. All of the other jewels in the net are reflected in each individual jewel, and each jewel reflected is also reflecting all of the other jewels. This metaphor describes what in Pali, the original language of the Buddhist canon, was called paticca samuppada, “dependent co-arising.” Modern Buddhist teachers have called it “interbeing,” or “the harmony of universal symbiosis.” This is a worldview of mutual intercausality, interconnectedness, and interdependence, a worldview from the same ecophilosophical galaxy as Alexander von Humboldt’s “cosmos,” and the “everything is connected” view at the heart of ecology.

In the realm of the major world “religions,” Jeffers focused his attention on the Western, Greek-and-Roman, Mediterranean-and-Middle Eastern, European tradition, especially Christianity. His father was a respected Presbyterian minister and theologian, and Robinson was steeped in that wordview growing up. He ultimately rejected it, with rebellious fire and fury.

He only mentions Asian philosophical and spiritual worldviews—Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism—in a very few places in his oeuvre. But his deep-time-embedded, evolutionary worldview certainly has much in common with the deepest currents of Buddhist thought. I’ve been burrowing into his philosophy and worldview via the most extensive, scholarly analyses of his work that exists, by historian and poet Robert Zaller. I’ve been reading Zaller’s books now for weeks, making it through perhaps a dozen pages a day, and learning a new word on almost every page; his analysis is academic, almost esoteric, insightful, and fascinating. Zaller seems to settle on calling Jeffers’s worldview “panentheism,” rather than “pantheism.” Probing the supposed distinctions of those terms via internet research, I think I’d call Jeffers’s worldview pantheism—which would place it close to the Stoic-Swedenborg-Net-of-Indra view. However, I’m not deeply familiar with the history of Western, Christian theodicy, as Zaller clearly is, so I may not be a sympathetic judge. For me, “what is the difference between ‘pantheism’ and ‘panentheism’?” has the same answer as “what is the sound of one hand clapping?”, a famous Zen koan.

In his Preface to The Double Axe, Jeffers explains his intention for that work:

It presents, more explicitly than previous poems of mine, a new attitude, a

new manner of thought and feeling, which came to me at the end of the

war of 1914, and has since been tested in the confusions of peace and a

second world-war, and the hateful approach of a third; and I believe it has

truth and value. It is based on a recognition of the astonishing beauty of

things and their living wholeness, and on a rational acceptance of the fact

that mankind is neither central nor important in the universe; our vices

and blazing crimes are as insignificant as our happiness. We know this, of

course, but it does not appear that any previous one of the ten thousand

religions and philosophies has realized it. An infant feels himself to be

central and of primary importance; an adult knows better; it seems time

that the human race attained to an adult habit of thought in this regard.

The attitude is neither misanthropic nor pessimist nor irreligious, though

two or three people have said so, and may again; but it involves a certain

detachment.

He chose eventually to call his view “inhumanism.” I guess maybe he did that because of his deep knowledge of Western philosophy, and the invention of the philosophy called “humanism.” If you go googling for definitions of humanism, you’ll find that it arose during the Renaissance through a renewed interest in Greek and Roman thought; it focused on humans and their needs and potential; and it was a secular, non-theistic view centered on human agency, and a reliance on reason rather than religion to understand the world. But the secularizing philosophy of humanism is as completely anthropocentric and human-supremacist as the pre-Renaissance Christian worldview was. It was still a Western, ego-centric worldview. Jeffers was looking for something different, I think. Something like what Alexander von Humboldt had been exploring a century earlier, what I’d call a “cosmocentric” worldview.

But by using the negative preface “in” in his neologism “inhumanism,” Jeffers opened himself to the suggestion that he was anti-human or misanthropic. Since most average Americans had likely never heard of the philosophy of “humanism” in the first place, most probably read “inhumanism” as “anti-human.” Jeffers tried his best to explain, saying that his view “is neither misanthropic nor pessimist nor irreligious.” But it was too complicated for the average person of his time to understand, I suspect.

Edward Weston, who had photographed Jeffers many times and was a Carmel neighbor and friend, wrote, in 1929, that “Despite his writing I cannot feel him misanthropic: his is the bitterness of despair over humanity he really loves” (Karmen, intro to Stones of the Sur, p. 5). James Karmen (Stones of the Sur, p. 4) says “People were important to him… but he saw human history within the context of natural history, and with an evolutionary view of life in mind, he embraced an astronomical and geological view of time. From that vantage point, all existence, including that of the entire human species, is ephemeral.”

In an essay from 1992, “Deep Ecology and Its Critics: A Buddhist Perspective,” I defended the philosophy of “deep ecology” against critics who claimed it was misanthropic, arguing that the Buddhist perspective of “interbeing” was reflected in the science of ecology and the web of life of Earth’s biosphere, and that if you really love humans you must love and defend the biosphere that is their only home. Looking back, I think I was trying to channel Jeffers’s “not man apart” worldview then.

Short of Patience

Alexander Pope’s poem “An Essay on Man” (1733-1734) contained the lines “Hope springs eternal in the human breast: / Man never is, but always to be blest.”

“Hope springs eternal” has become a catchphrase for the perennial tendency of our species toward optimism. The fact that hope springs eternal may be the result of our evolution as humans. Our bent toward optimism, and toward an idea of “progress” and that “the future will be better,” may have kept our ancestors going in the darkest times over the past few million years. Such as when, for example, the volcano Toba erupted in Indonesia 74,000 years ago, the largest explosive volcanic eruption on Earth in the previous few hundred thousand years. Toba is thought to have caused a “volcanic winter,” similar to “nuclear winter” scenarios, a global ecological disaster of darkness and cold with severe reductions in photosynthesis and ecological productivity, especially in the tropics. Some researchers think humans may have been on the brink of extinction at that time, with a total population of fewer than 10,000 thousand individuals—a global population no bigger than a small town now.

Norman Vincent Peale’s bestselling book The Power of Positive Thinking, was published in 1952 (I was one, Jeffers was 65). It was on millions of bookshelves across the U.S., including my mother’s. Peale’s book rode the wave of post-World War II economic- and baby-booming in the United States and promoted the worship of optimism. At the same time, the nuclear arms race accelerated; both the US and USSR developed hydrogen bombs that were orders of magnitude more powerful than the fission bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and threatened each other using increasingly hostile rhetoric. The Korean War was on, the US fighting again in Asia against the new communist Peoples Republic of China.

What’s wrong with this picture? Jeffers was asking that question. He asked it, for example, in his poem “The World’s Wonders,” first published in Poetry magazine in January, 1951, a month before I was born.

Being now three or four years more than sixty,

I have seen strange things in my time. …

I have seen my people, fooled by ambitious men and a froth of sentiment, waste themselves on three wars. None was required, all futile, all grandly victorious. A fourth is forming.

I have seen the invention of human flight; a chief desire of man’s dreaming heart for ten thousand years; And men have made it the chief of the means of massacre.

I have seen the far stars weighed and their distance measured, and the powers that make the atom put into service –

For what? – To kill. To kill half a million flies – men I should say – at one slap.

He commented on the “strange things in my time” in “De Rerum Virtute,” (1953)

The bitter futile war in Korea proceeds, like an idiot

Prophesying. It is too hot in mind

For anyone, except God perhaps, to see beauty in it. Indeed it is hard to see

beauty

In any of the acts of man: but that means the acts of a sick microbe

On a satellite of a dust-grain twirled in a whirlwind

In the world of stars. …

Something perhaps may come of him; in any event

He can’t last long. – Well: I am short of patience …

In the first line of his poem “The Answer,” Jeffers advised us “not to be deluded by dreams.” Now, the bestselling book Abundance (Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, 2025) presents a technologically optimistic vision of the American future based on deep ecological ignorance, or at least illiteracy. But it seems to have created a buzz among political liberals and progressives who hope for optimism – it’s a “New York Times #1 Bestseller.” They are deluded by dreams, and Jeffers would have sharp words for them, as he did for the liberal reformers of his day – including FDR, for example. Of course, a book titled Abundance has better market potential with the current “me-too” mindset than would one with a title like Scarcity: Lessons for Living Happy in the Overshoot Age (Don’t steal my title—I’m working on the manuscript now!).

I remember, though, books with titles like Limits to Growth, Design with Nature, Small is Beautiful, and Living the Good Life – books that captured the longing of baby-boomers in the 1970s (me too) to somehow get our society back in balance with the obvious ecological “abundance” of Earth’s ecosystems, at a time when it was clear we had already trespassed against those planetary ecological limits and exceeded our ecological carrying capacity. The Population Bomb, by Stanford ecologist Paul Ehrlich, was published in 1968, when there were about two and a half billion people on Earth. Now there are eight billion. Has the bomb exploded yet?

We are living in the Dark Ages: of human overpopulation; the idea of nations as stable institutions; the idea of national sovereignty over Earth’s geography and ecosystems being OK; and the idea of individual and societal “progress.” Our so-called progress has been mostly toward egotism and tribalism, justified by the Western worldview of divinely blessed human supremacism. Now the most powerful global empires (the United States, China, and Russia) are competing for global resources, all armed with nuclear weapons, and believing that those nukes give them strategic leverage in this global competition. Nuclear war is the ultimate environmental threat to the planet, and an existential risk to our species. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has placed their “Doomsday Clock,” which has been tracking the risk of nuclear Armageddon since 1947, at 89 seconds before midnight, closer than it has ever been before (Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, “The Clock Shifts”).

Optimism has a downside. It may motivate against learning from history, and discount its dark episodes from which we could learn much, and perhaps change course. Could pessimism sometimes be adaptive, and optimism dangerous?

Oh, Robin, I am short of patience too! What a world, what a foolish species we are members of! A few months ago, this poem found its way out and onto paper:

Taking Measure (for Robin Jeffers)

Some measure of misanthropy is warranted.

Man is not the measure of all things,

is not apart, only thinks so.

And thus our wantonness,

discarding all Earth’s beauty

to feed our greed.

It cannot last long.

It cannot last much longer.

Earth will purge herself

of our overrun.

Maybe a few will survive

to found a more humble race.

(Poem 10 May 2025)

What Should We Do?

If we are living in a new Dark Ages, what should we do? What’s the answer? In his poem “The Answer,” Jeffers gave some suggestions. I’ve already noted “not to be deluded by dreams,” from the first line of that poem. What else?

To keep one’s own integrity, be merciful and uncorrupted and not wish for evil;

and not be duped

By dreams of universal justice or happiness. These dreams will not be fulfilled.

That sounds like sensible advice. We each have “agency” over our own actions, even if they are embedded in system over which we have no control, and hardly any influence.

But should we have hope? Hope for the future, if our dreams “will not be fulfilled”? Jeffers’s view of the role of the poet in a democracy, Elliot Ruchowitz-Roberts said in his talk in Carmel that evening, is “one who does not provide false hope for a future based on dreams.”

Jeffers counselled that “hope is not for the wise” in his 1937 poem with that title.

Hope is not for the wise, fear is for fools;

Change and the world, we think, are racing to a fall,

Open-eyed and helpless, in every newscast that is the news:

The time’s events would seem mere chaos but all

Drift the one deadly direction.

But, in the last lines of the poem, Jeffers points us to a viewpoint that transcends hope to something more durable. If we aren’t deluded by dreams, and fooled by hope, so what? The solace he shows us is in embracing our embeddedness in the cosmos.

But if life even

Had perished utterly, Oh perfect loveliness of earth and heaven.

In “The Answer,” Jeffers gives his deepest answer, I think, linking back to his cosmocentric, Net-of-Indra worldview (even though he did not call it that):

Integrity is wholeness, the greatest beauty is

Organic wholeness, the wholeness of life and things, the divine beauty of the universe.

Love that, not man

Apart from that, or else you will share man’s pitiful confusions, or drown in despair when his days darken.

It is from these lines that the three words that captured my imagination, and that of the environmental movement of the 1970s, came: “not man apart.” In my most recent book, Nature on the Edge: Lessons for the Biosphere from the California Coast (2024), I wrote:

Even if it doesn’t give me “hope,” looking at our current situation from a deep-time perspective gives me some solace. The biosphere will be fine, ultimately, no matter what we do. It has survived five mass extinction events already in the 4.5 billion-year history of life on Earth, and will survive the “Sixth Extinction,” now being caused by us. In a few tens of millions of years, the biosphere will emerge from this anthropogenic Sixth Extinction with even more biological diversity than the world our species evolved into.

Whether the human species survives it is another question. I have my doubts, but I love my creative, hyper-cultural species, and I like to imagine an evolved descendent-species of ours carrying through into that post-human future with some elements of our uniqueness and evolutionary brilliance, but having left our destructive tendencies behind.

So how much time do we have? It is already too late to do what we knew we needed to do long ago. But at the same time, it is never going to be too late; life on Earth is very resilient, and doesn’t really need us at all.

Jeffers wrote “Perhaps the other animals will make a new world / When mankind’s out.”

Rather than hope, given that it is not for the wise, we can still find solace in the “sublime,” that great beauty of the deep time and organic wholeness of the universe:

What a pleasure it is to mix one’s mind with geological

Time, or with astronomical relax it.

There is nothing like astronomy to pull the stuff out of man.

His stupid dreams and red-rooster importance: let him count the star-swirls.

— final lines from “Star-Swirls” (1962)

In the Preface to The Double Axe (original version 1947, in Hunt), Jeffers wrote:

To sum up the matter: — “Love one another” is a high commandment, but it polarizes the mind … Turn outward from each other, so far as need and kindness permit, to the vast life and inexhaustible beauty beyond humanity. This is not a slight matter, but an essential condition of freedom, and of moral and vital sanity.” (Hunt, p. 721)

So, what should we do? In his Preface to The Double Axe, Jeffers proposed that “We could take a walk, for instance, and admire landscape… We could dig our gardens… We could, according to our abilities, give ourselves to science or art, not to impress somebody but for love of the beauty that each discloses. We could even be quiet occasionally.”

Jeffers demands—yes, still now, present tense, as he did for his contemporaries when alive—that we think deeply. He doesn’t let us get away with the usual shallow, self-absorbed, temporally myopic view that our society expects and cultivates. We have a chance, once again, to celebrate his brilliance and apply his relevance for our time. With the proper attitude and understanding, the true worldview, we won’t drown in despair even as our days darken.

In the cosmocentric worldview he constructed for himself and invited us to share, “we” are OK, and will always be, no matter what. Because “we” are the supernovae where the elements in our bodies were created; the creation of solar systems, our sun and Earth and the other planets; and all of life—ours and the viruses and bacteria that sicken and sometimes kill us. We are the struggle for existence; the evolution of life; unqualified presidents and dictators; and peasants and citizens of democracies and dictatorships who lick their boots and kiss their asses, all the while too busy to think about what it all means because they are all struggling for daily life. And we are the invention of nuclear weapons, and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the nuclear winter that may come one day.

We are OK because the universe doesn’t care a bit and is beautiful. We are timeless atoms in a universe of organic wholeness, jewels in the Net of Indra, and it is beautiful.

Sources

Gelpi, Albert. 2003. The Wild God of the World: An Anthology of Robinson Jeffers. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA.

Hunt, Tim. 2001. The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. Edited by Tim Hunt. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA.

Karman, James. 2015. Robinson Jeffers: Poet and Prophet. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA.

Karman, James. 2001. Stones of the Sur: Poetry of Robinson Jeffers; Photographs by Morley Baer. Selected and Introduced by James Karmen. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA.

Reece, Erik. 2020. “Bright Power, Dark Peace.” Harper’s, September 2020. https://harpers.org/archive/2020/09/bright-power-dark-peace-robinson-jeffers-tor-house/

Zaller, Robert. 2012. Robinson Jeffers and the American Sublime. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA.

Zaller, Robert. 2018. The Atom To Be Split: New and Selected Essays on Robinson Jeffers. Tor House Press: Carmel-by-the-Sea, CA.

Notes

1 Google Ngram for “Robinson Jeffers” https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=Robinson+Jeffers&year_start=1800&year_end=2022&corpus=en&smoothing=3

2 Maria Popova, 2019, “Robinson Jeffers on Moral Beauty, the Interconnectedness of the Universe, and the Key to Peace of Mind,” The Marginalian. https://www.themarginalian.org/2019/06/03/robinson-jeffers-sister-mary-james-power/

January 23, 2026 1:37 pm

This is a wonderful essay, Bruce, and I like where it ends up. The catalog of terrible human behavior is a little hard to contemplate first thing in the morning, but the end of your essay is, yes, hopeful. Thanks.