July 2015. In a previous story about my July trip to the Colorado high country, I got in a dig at Coors beer – well-deserved in my view. In another story from that trip I talked about the relationship between the American idea of wilderness and the concept of the sublime, and mentioned in passing how Native Americans fit into that worldview. I’ll pick up on threads of those stories here, but also pull in another more distant thread: a blog from a trip to Rwanda in September, 2014, “Forest of Hope: A Visit to Gishwati Forest.” I started that story with:

“Sipping a draft Mützig in the patio restaurant at the hotel in Gisenyi, lightning flashing out over Lake Kivu. Storms still around, after the fierce downpour this afternoon driving from Musanze to Gisenyi, where we stopped along the Sebeya River to see the raging torrent of liquid mud, as if the rain had punctured an artery of the land, and now it was gushing its red-brown blood. Mützig is a bright, honey-colored lager with enough hoppiness for my taste, one of the popular Rwandan beers made at the Brailirwa Brewery here in Gisenyi, now part of the giant global Heineken brewing family. It’s made from that muddy water from the Sebeya.”

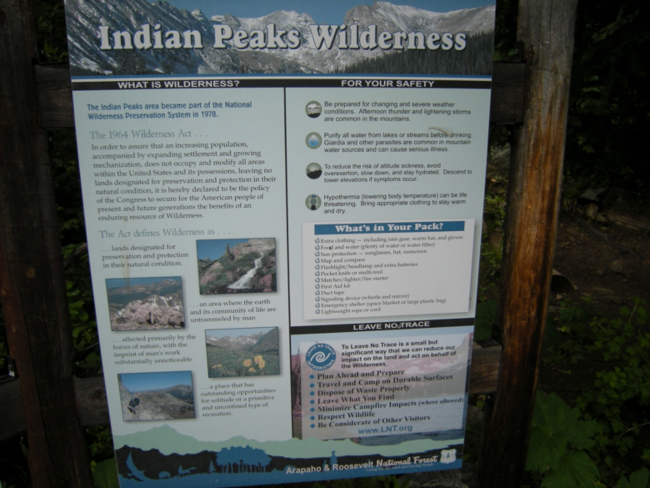

To an ecological mind, everything’s connected to everything else, of course, and so as I was sipping a draft Indian Peaks Pale Ale at the Walnut Brewery in Boulder, after a day of wandering above tree-line in the Indian Peaks Wilderness, all of the interconnections began to interconnect. The water that brewed this beer I was sipping came from the Indian Peaks Wilderness Area, in the Arapahoe & Roosevelt National Forest – a pristine, “sublime” source compared to the mine-polluted water of Clear Creek used by Coors, or the muddy water of the Sebeya River in Rwanda.

The city of Boulder has its own protected watershed, a slice of one of the main tributaries of Boulder Creek, which originates from mountain snows and the meltwater of the Arapahoe Glacier that occupies the cirque below the Arapahoe Peaks on the Continental Divide. The city takes its water supply seriously, and this scenic mountain area called the Green Lakes Valley is completely off-limits to any human entry except for watershed guards and managers. Fishermen who try to sneak in to fish its lakes risk a large fine. To the south is National Forest land open to public use, and a trail starting at Rainbow Lakes gives access to treeline and the ridge leading up to the Arapahoe Peaks. On the north side of the watershed is Niwot Ridge, a long finger of alpine tundra reaching eastward from the high peaks. All of this lies within the Indian Peaks Wilderness.

Niwot Ridge is named after Chief Niwot (1825–1864), a principal chief of the Southern Arapahoe, who often camped and hunted with his people in the Boulder Valley. He was also known as Chief Left Hand because he was left-handed. Several geographical features near Boulder, such as Left Hand Canyon, use that name for him. So does the Left Hand Brewery, which like the Walnut Brewery, also uses water originating from the Arapahoe Glacier watershed to brew its brews. Left Hand was killed in the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864.

Niwot Ridge is a Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) site managed by the University of Colorado’s Institute for Arctic and Alpine Research and their Mountain Research Station. The Long-Term Ecological Research Network was created by the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 1980 to conduct research to understand ecological processes operating on long time scales, and large, landscape-level spatial scales. Long-term ecological research provides the data needed to document and analyze ecological change. The Niwot Ridge LTER site was established in 1980 with support from NSF. The topography, climate, and ecosystems of Niwot Ridge are representative of alpine ecosystems in the southern Rocky Mountains, including extensive expanses of tundra and subalpine coniferous forests, as well as mountain glaciers, a variety of glacial landforms, lakes and moraines, cirques, talus slopes, patterned ground, and permafrost. The LTER site includes Niwot Ridge, the City of Boulder Watershed in the Green Lakes Valley to the south, and the University of Colorado’s Mountain Research Station (MRS). Niwot Ridge has been designated a Biosphere Reserve by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) – an internationally-prestigious honor.

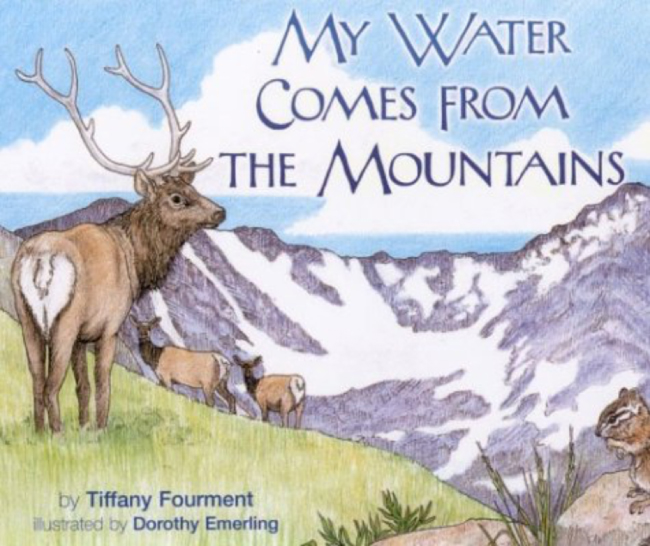

In the early 2000s, the University of Colorado’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, which runs the Niwot Ridge LTER site and Mountain Research Station, wanted to reach out to the public and make a connection between its long-term alpine research and the lives and interests of residents of Boulder and other local downstream communities. One result of that effort was a children’s book, titled My Water Comes from the Mountains. The storyline of the book: Mountain ecosystems provide and protect the water supply you depend on every day; you should recognize that, and support the ecological research and environmental conservation needed to ensure that they continue to do so.

The grown-up version of this kids’ book – coming soon to bookstores near you? – is My Beer Comes from the Mountains, sketched here for the first time in this blog. It will explore the interconnections between the history and philosophy of American nature conservation, long-term ecological research to provide a basis for understanding human-caused environmental change, and human well-being – including, of course, how natural ecosystems are the key to good water to brew a good beer!

Ah! A final sip of my sublime Indian Peaks Pale Ale. I can taste all of the complex ecological and cultural interconnections. I hope these musings let you imagine them too, until you have a chance to see and taste them yourself.

View of the Arapahoe Glacier between North and South Arapahoe Peaks, Indian Peaks Wilderness, July 2015

For related stories see:

- Forest of Hope: A Visit to Gishwati Forest

- The View from Zomba Mountain: Plants, Water, and People in Southern Malawi

- A Sunday on Cerro Guanacaure, Honduras

- Ecohydrology of the Honduran Highlands

Sources and related links:

- Walnut Brewery Indian Peaks Pale Ale

- Indian Peaks Wilderness, USDA Forest Service

- Chief Niwot

- Sand Creek Massacre

- Left Hand Brewing Company

- Niwot Ridge LTER Site

- University of Colorado Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research

- University of Colorado Mountain Research Station

- Long-Term Ecological Research Network

- Niwot Ridge Biosphere Reserve, UNESCO

- My Water Comes from the Mountains