October 2014. Cyamudongo is a small forest fragment southwest of the mountain forests of the Nyungwe National Park in southwestern Rwanda, and is administratively part of the park. Cyamudongo – the “cya” is pronounced “cha,” but with a soft “c” so it almost sounds like “sha” – has a population of chimpanzees that are relatively easy to track and find, since the forest is so small, making this one of the premier places in the world for wildlife tourists to see our closest evolutionary relatives.

We left the lodge in Rusizi overlooking Lake Kivu at about 8:20 AM, and arrived at the edge of the forest about 9:30. We weren’t chimp tourists; with my Rwandan colleagues Emmanuel and Serge, we were a team of consultants hired to conduct an environmental threats and opportunities assessment for the US Agency for International Development (USAID), working under a contract with ECODIT, a consulting firm based in Arlington, Virginia. A small group of local people met us at a community tourism center at the edge of the forest, which had been funded by USAID through the “Nyungwe Nziza” Project. We met with this group for almost an hour, hearing about their hope that forest conservation and chimpanzee tourism could provide employment and income for their community, and the challenges of making that vision into a reality.

After the meeting, one of the community members accompanied us a couple of kilometers farther along the road around the forest edge, with the goal of seeing some beehives that the project was supporting in a Batwa community. It turned out that the beehives were a 45-minute hike away, across a deep gorge, and we didn’t have time to go see them. But we did meet the Batwa. Later, Emmanuel, my consulting team colleague, said “You can’t call them Batwa in the report – remember that, don’t write that! They have to be called, officially, “historically-marginalized communities.”

Throughout Africa there are former “hunter-gatherer,” forest-dweller ethnic groups that are often – no, usually – marginalized in modern countries. They are probably – no, undoubtedly – the aboriginal, autochthonous, “indigenous” inhabitants of the land. Sometimes, as with the Batwa in Rwanda, these forest people are genetically small in stature, and sometimes called “pygmies”. These aboriginal peoples and cultures were washed over by tides of other expanding ethnic groups, whether agriculturalists – Bantus from the west – or cattle-keeping pastoralists – Cushitic speakers from the northeast.

The tallest men here in this Batwa village were up to my mid-chest, about 4-1/2 feet tall, but stocky and strong-looking. The women were smaller, and the children tiny. But the most striking thing was the poverty. I didn’t see the telltale signs of kwashiorkor, protein malnutrition, which I’ve seen in some coastal villages in Mozambique. But I did see unwashed, coughing, snot-nosed children, some with mothers who looked like children themselves, no more than 14 or 15 years old. Some kids were chewing on raw cassava stalks for breakfast.

Cyamudongo Forest used to be their home territory. One man told us that their parents had gradually sold all this land, right at the edge of the forest, to farmers. Finally the Ministry of Local Government bought some of the land back, and built this village for them. The “village” was one long dirt street with two rows of eroded mud-brick houses facing it from each side. Emmanuel, my Rwandan assessment team member, asked one Batwa man why they still went into the forest to hunt bushmeat and gather wild fruits. “We don’t have bananas like those on the farms of the Rwandan citizens that you see here around our the village,” he answered. Indeed, the Batwa village was surrounded by banana fields, apparently not owned by the Batwa residents. Emmanuel was amazed, because that response implied that the Batwa man didn’t consider himself a “Rwandan citizen,” although he clearly lived in Rwanda. Maybe he considered himself a citizen of the forest. As the chimpanzees are.

We saw the village water tap – one spigot, with a broken handle, so it dribbled water but couldn’t be turned fully on or off. This water supply system was built by the Ministry of Local Government when the village was built, and it tapped a water source in the Cyamudongo Forest. The idea was that it would keep the Batwa from going to that spring to collect water, and therefore help to stop them from collecting firewood, medicinal plants, wild fruits, and an occasional bit of bushmeat – all of the things their ancestors got for free from the forest – when they went for water. But the water tap is obviously not maintained by anybody now, the Ministry or the community.

As we were leaving we encountered a short, burly man with a headload of split firewood as big as he was, coming into the village from the forest. Driving back up the road we saw a man bringing plastic jugs of water out of the forest, probably from the spring that was supposed to feed the broken water tap.

After visiting the village we stopped at the ranger post just inside the forest above the community center where we had the earlier meeting. Here we met a group of about ten rangers and chimpanzee trackers, employees of Nyungwe National Park, who are charged with protecting the forest and finding chimpanzees for tourists to see. When we mentioned the Batwa, they exploded with stories: “OK, we did hire a Batwa once as a tracker, but when he got paid you wouldn’t see him again until he had spent all the money!” And “Oh, one day a Batwa we had hired disappeared when we were on patrol in the forest. Some other rangers arrested him four days later with an antelope he had poached!” It seems like there is a deep cultural gap between the Batwa – er, pardon me, “historically-marginalized communities” – and many of the national park staff who have to interact with them.

The idea of significant ethnic distinctions doesn’t sit well in post-genocide Rwanda. In fact, it is supposedly illegal to call attention to someone’s ethnic background, for fear, I suppose, of reviving old hostilities. No wonder, really. But the Batwa, according to my Rwandan colleagues, call themselves “Batwa” – not “historically-marginalized communities.” Obviously, if they don’t consider themselves Rwandans, they consider themselves something – and that identity is Batwa. The nation-building government of Rwanda isn’t happy with that idea, doesn’t seem to want to hear it, and doesn’t seem to have a plan to deal with it.

But our visit to a Batwa community was very revealing. This is a different world: a minority community with a different worldview in a country that is understandably nervous about recognizing such differences because of its traumatic history. According to Serge, the Batwa are demographically endangered. At the time of the genocide, he said, it was estimated that there were 200,000 Batwa; now the estimate is 20,000.

Across Africa, not to mention the rest of the world, it is very, very hard to know how to deal with and work with minority cultures that are significantly “counter-cultural” to the dominant modern culture – as the Batwa are. The “historical marginalization” of the Batwa in Rwanda is in many ways parallel to the marginalization of the Batwa’s equivalent in Kenya, the Ogiek of the Mau Forest, or even to pastoralist cultures in neighboring Tanzania and Kenya, the Masai and others. A hopeful model for future rights-based development of the Batwa might be the case of the Hadza of Tanzania – another of the autochthonous ethnic groups of Africa who have recently regained some rights over their ancestral land.

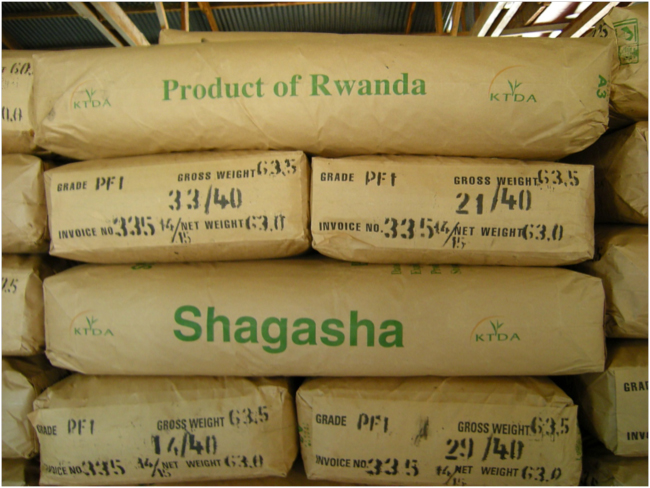

After leaving the Batwa, and the Cyamudongo rangers and trackers, we drove away from the forest. The road descended gently through a landscape of emerald tea bushes belonging to the Shagasha Tea Company. Moise, the field coordinator of the Nyungwe Nziza project who was coordinating our visit to Cyamudongo, had a personal friend who worked for the tea company as the production manager, in charge of all the technical aspects of turning these green hillsides into a global commodity. When we expressed our interest in visiting the tea factory, and getting their views about Cyamudongo Forest, Moise called his friend Dominic, and we had an immediate appointment.

We put on freshly-laundered white lab coats and caps to cover our hair, and plunged into the tea factory with Dominic. First we saw the baskets of freshly picked leaves being hung on a conveyor belt and dumped onto steam-heated wilting tables, the first step in taking the water out of the leaves. We descended some stairs into a giant warehouse-like building, where automated machines started the chopping and heating process that transforms the wilted green leaves into the fermented “black” tea that gives much of the world a brisk, refreshing, pick-up, charged with caffeine and theobromine – oh so “civilized!” Rwandan tea has lately been performing very well in world tastings, almost matching some Kenyan tea that has recently set the standard of quality for Africa. The wonderful, rich, sweet smell of tea filled that big building like a tea-drinkers heaven.

After the tour of the factory we spoke with the factory manager, a Kenyan, brought here to push the standard of quality higher. We asked him whether the nearby forest, Cyamudongo, had any importance to the operation of the tea factory, and were very surprised. We hadn’t expected such a strong, positive response. “Without Cyamudongo Forest we would be out of business,” he said immediately. He gave two reasons. One was that clean water is needed to make the steam heat for the wilting tables, and which further dries the leaves and catalyzes the enzymatic reaction that transforms them into fermented black tea. If they didn’t have pure water from the forest they would have to treat it, and that cost would eat into their bottom line. Another reason they depended on the forest, he said, was because of its influence on local climate. Tea bushes don’t produce well if they experience water stress, he explained, and their upper fields, bordering Cyamudongo, give them their best production because the forest attracts and creates clouds and fog. Precipitation and humidity next to the forest are higher.

We left Shagasha and descended back down to Rusizi on the shore of Lake Kivu, the day sunny and warm, and ate lunch at a local hotel, a typical starch-rich Rwandan buffet, plates piled high with potatoes, rice, plantains, beans, vegetables, and some meat, maybe chicken, or tough stewed beef.

I was struggling to make sense of the contrasting images of the morning’s visit to Cyamudongo Forest, but I knew, somehow, that chimpanzees, the Batwa, and tea were connected. I just couldn’t picture a Batwa sipping from white porcelain, or a British pensioner knowing that a forest full of chimpanzees gave their tea its refreshing flavor. I was struggling for connections, solutions, ways forward.

The manager at Shagasha Tea Company had clearly said that the company was willing to work with local communities to protect the forest because of their dependence on it for their bottom line. Maybe, just maybe, they could invest a little bit of money to fix the tap in the Batwa village, and start a conversation between the Batwa, the local community trying to develop tourism opportunities, and the national park managers, and… who knows where this conversation would end, exactly? But it would at least begin with the incredible, unrecognized value of this little leftover bit of natural forest, habitat and haven for chimpanzees, Batwa, and tea.

For related stories see:

- Searching for Grauer’s Swamp-Warbler at the Top of the Nile

- Islands of Biodiversity in the African Sky: Golden Monkeys and Irish Potatoes

- Forest of Hope

- Mukura Forest Calling

Related links:

- Rwanda Environmental Threats and Opportunities Assessment 2014

- ECODIT

- Nyungwe Nziza Project

- The Hadza people of Tanzania

April 26, 2015 12:08 am

This post on Rwanda – and dubbing groups like the Batwa “historically marginalized communities” – came back to me when I read an article in the Christian Science Monitor this week titled “In Rwanda, progress and development scrub away an ethnic identity”

(http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Africa/2015/0414/In-Rwanda-progress-and-development-scrub-away-an-ethnic-identity). The article calls them the Twa ethnic group, but I assume that’s the same as Ba-twa. The CSM article points out many of the same conflicts that you did between minority communities and development.