Western face of Mount Mulanje from the road between Blantyre and Mulanje town

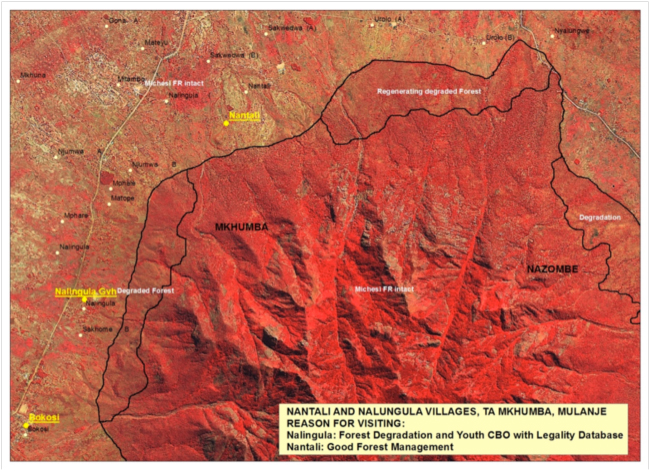

April 2013. Mount Mulanje rises like an island above the rolling landscape southeast of Blantyre in southeastern Malawi. By examining images taken by the French SPOT 5 Earth-observation satellite, the Malawian team I was working with on an evaluation of USAID-funded biodiversity conservation projects had identified a pair of contrasting villages on the northern end of the massif, bordering the Mount Mulanje Forest Reserve. On a SPOT image taken from over 800 kilometers in space, but with a resolution of ten meters or less that could show individual trees, a sharp boundary could clearly be seen between the deep red, rough texture of trees in the forest reserve and the paler colors indicating cropland around the village of Nantali. To the south, around the corner of the mountain, the village of Naligula was located almost the same distance from the boundary of the forest reserve, but there a weaker red color and smoother texture indicated degraded woodland above the village in the reserve. Woodland degradation could also be seen on the SPOT image to the east of Nantali, above the village of Urolo. Our plan was to go to these villages to try to understand the causes of these differences in behavior toward woodlands that can be seen from space.

SPOT 5 image of the northern section of the Mount Mulanje Forest Reserve

We drove to Nalingula Village on the main gravel road heading north from the dusty district capital of Phalombe on a warm, sunny morning. Where we parked, a giant pile of bricks stood beside the road. The beautiful red local bricks used in house construction here are fired in wood-fueled kilns. It takes a lot of wood to fire a pile of bricks that big, and we had seen many other piles like it on the road from Phalombe. The condition of the woodland on the mountainside above the village told the story of intensive wood harvesting only too clearly, confirming the interpretation of the satellite image. There were almost no large trees for several kilometers up the slope into the forest reserve.

Looking east toward the Forest Reserve from Nalingula Village

In the village a small group was expecting us. They were members of a community-based organization called “Hope for Life.” There were more women than men in the group, and their leader was an enthusiastic woman. The conversation veered between English and Chichewa; the chairwoman spoke good English. The cause of the deforestation in the protected area above Nalingula, they said, was mainly charcoal making, but also firewood cutting, timber sawing, and cutting wood for brick-kilning. Some of these products sold to urban markets like Phalombe, Mulanje, and even Blantyre and Zomba. They knew the people who were making charcoal and cutting and selling wood illegally, and they had reported them to authorities in the past, they told us. But those people were never stopped, and the cutting went on. We wondered whether that was because some of those making money from the illegal activities were Forest Department staff or traditional authorities themselves.

Our hosts from Nalingula Village, members of the community-based organization “Hope for Life” at the boundary of the Mount Mulanje Forest Reserve

After they had explained the story behind the situation, we set out uphill at a brisk pace through the village fields toward the mountain. We wanted to “ground truth” the satellite image up close, with our own eyes. The subsistence farming system here was diverse and sophisticated, with intercropping of many traditional African crops: sorghum, millet, pigeon peas, chickpeas, groundnuts, cassava, maize, bananas, mangos, and papayas. As we went higher and the slope got steeper, the fields became pockets of dry soil between granite rocks and boulders, with stunted maize and pigeon peas that didn’t really look like their yield would be worth the effort of cultivation. Food pressure here must be intense to press farmers onto marginal land like this. The hardscrabble fields stretched right up to the boundary of the forest reserve, which was marked by a narrow path, above which was a wall of thatching grass taller than a person. Here our guides paused for a photo before leading us into the reserve.

Members of “Hope for Life” who accompanied us into the Forest Reserve resting at our turnaround point beside a small stream

At least the crop fields didn’t extend beyond the boundary line as we proceeded up into the reserve, and all around us now we could see native miombo woodland trees resprouting from stumps and roots. We rested and turned around at a small stream after walking into the reserve for half a kilometer. Above us all the trees had been cut for as far as we could see. But all around us they were making a comeback, resprouting, a revolution against the cutting and charcoal making.

Natural resprouting of cutover miombo woodland inside the Forest Reserve above Nalingula Village

After descending again from the cut over but regenerating woodland above Nalingula, we said goodbye to our hosts from the “Hope for Life” group, and as we drove north to their sister village of Nantali our heads were swirling with questions. We stopped in a thronged trading center on the main road and bought cold Cokes at a small shop before proceeding on to Nantali Village on a rough dirt track toward the mountain. Again we were greeted by a group who had been expecting us, alerted by cell phone by our hosts from the MOBILISE Project, the USAID-funded project whose activities we were evaluating here. MOBILISE, which stands for “Mountain Biodiversity Increases Livelihood Security,” is being implemented by the Mount Mulanje Conservation Trust (MMCT).

Village Headwoman, Nantali Village

As usual, we sat and talked in the shade of a big tree. The head of the village here was a woman, and her leadership, backed up by that of the headman of the local group of villages, and the even-more-powerful traditional leader, the chief or “traditional authority,” had protected the woodlands in the Forest Reserve above the village since 2008, they told us. At that time, a wave of charcoal-making was sweeping into the area from the Urolo area to the northeast, threatening to clear the trees above them. They resisted, and chased away the charcoal-burners. Those same charcoal-makers may be some of the ones who moved on to Nalingula, where we had just seen the results.

Among other questions, we asked these people where their water came from, reminded by a tap that was frequently in use not far from where we were holding our meeting under the tree. It comes from an intake on a stream inside the Forest Reserve above the neighboring village of Urolo, they said, and is gravity-fed here to the village. The trouble is, they told us, Urolo did not resist the charcoal-makers, and the forest within the protected area was cut. Nantali’s water supply dam and intake is now threatened by floods and siltation from the deforested area upstream.

Community water tap, Nantali Village

We again wanted to see the Forest Reserve boundary on the ground, so again we set out for a hike of a kilometer or so up through village fields and houses. The sharp line of big old miombo woodland trees was striking, and for a few hundred meters below the boundary, above the village fields, we were again in a zone of resprouting woodland trees.

Mature miombo in Forest Reserve above Nantali Village

Sharp line of the Forest Reserve boundary above Nantali, resprouting miombo in foreground

After lingering awhile in the old woodland, we descended to the village. We said our goodbyes, again pondering these contrasting situations. What had we seen, and what did it mean? In one case a village, led by a woman, in which the traditional authorities and values had protected natural woodland near the village. In another village, a rebellious community-based organization, led and dominated by women, struggling against traditional leadership that we suspected is involved in an illegal and corrupt economic relationship with forest guards and charcoal makers that had managed to cut all the natural woodland close to the village.

A few days later we had a chance to talk to people in Mphalamando Village, in the Nkhotakota District, in central Malawi. Their village is less than a kilometer from the boundary of the Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserve, on the eastern side, not far from the shores of Lake Malawi. We heard a fascinating tale of how gender issues led to village-level forest conservation. In 2008, they said, they finally decided to set up a village forest area, and allow native woodland to regenerate on village land. The reason was that for years village woman had been caught gathering firewood and other woodland products inside the Wildlife Reserve by guards from the Department of National Parks and Wildlife, and they had been abused in one way or another. Finally, when they were beaten, and dropped on the road 30 kilometers away and made to walk home, the community decided that was the last straw. In order to protect their women from being subjected to that abuse, they decided to restore the woodland that was the source of those products. With the consent of the chief, the support of the Kulera Project, and help from the Department of Forestry, they have made a part of their village land a designated “Village Forest Area.” Thanks to the resilient miombo biodiversity, it is rapidly becoming a source of wood, mushrooms, wild fruits, traditional medicines, and other products once again. It is also providing ecosystem services, including allowing water to infiltrate the ground during the rainy season, feeding the water table that is tapped by village wells during the dry season.

Village meeting in Mphalamando Village

Natural regeneration of woodland in the Mphalamando Village Forest Area

A pattern, and a hypothesis, seemed to emerge from these village visits. It is women who gather firewood, cook food, fetch water. They also gather mushrooms, wild fruits, and often traditional medicines. Women’s traditional roles in supporting their families put them on the front lines of contact with the ecosystem products and services they depend on. Maybe we shouldn’t be surprised that women in these traditional villages are also on the frontlines of defending the natural forests from which they derive these essential livelihood resources. Maybe projects that seek to conserve biodiversity should recognize that women are likely to be allies and supporters, and make special efforts to work with and empower them.

For background on the evaluation of USAID-Malawi biodiversity conservation projects in which the village visits described here were made, see: “Restoring Miombo Woodlands for Village Development in Malawi”

For more photos of Malawi see: Malawi Biodiversity Projects Evaluation March-April 2013

Related links: