April 2013. Matupi Village, in the Rumphi District of northern Malawi, is tucked in a valley on the southern border of Nyika National Park. We reached Matupi on a warm, sunny afternoon, after a long drive on rough dusty roads. It was the end of the rainy season, the land was drying out, the maize harvest starting. Men and women were working with a hand-cranked bailer in the shade of some big trees, compressing dry burley tobacco leaves into 100 kilogram bales wrapped in burlap for transport to the tobacco auction floors. Small-scale tobacco-growing is an important cash crop in these villages.

Matupi Village with foothills of Nyika National Park in the background

Matupi sits on a ridge above a small river flowing out of the national park, and we could hear its rapids rushing in the gentle valley below. On the other side of the river a few fields and houses scattered up the slope, and a distinct line in the vegetation marked the boundary of the national park, about a kilometer from where we stood. Above the line was woodland, thick and relatively intact; below it the trees were shorter, smaller, thinner. Apparently the boundary had been more or less respected here, and crop fields had not even pushed up to the edge of the park.

Foothills of Nyika National Park from Matupi; line between thinned woodland in forground and protected woodland indicates park boundary

We were visiting communities in the border zone of the park that have been supported by a USAID-funded project called “Kulera,” which in Chichewa, the main indigenous language of Malawi, means “to look after” or “to nurture.” The Kulera Project has been implemented by Total Land Care, a Malawi-based non-governmental organization supporting rural development, along with other partners, since 2010. Its goal is to protect biodiversity through providing biodiversity-friendly livelihood opportunities, and by supporting processes through which villages in the border zones of protected areas can “co-manage” and harvest certain natural resources just inside the protected areas.

The purpose of our visits was to evaluate, for USAID-Malawi, whether the Kulera Project had been successful in achieving its goal of conserving woodlands and their biodiversity on the borders of several protected areas in central and northern Malawi, including Nyika National Park. Our evaluation team was organized and contracted by ECODIT, a US consulting firm, and included team members from the Centre for Development Management (CDM), a small Malawian consulting firm based in Lilongwe.

We wanted to understand what worked and what didn’t, the successes as well as the failures. Our basic evaluation philosophy was that conserving biodiversity and promoting sustainable development is a “work in progress,” and a “moving target.” No one really knows how to influence the trajectory of complex social-ecological systems – such as these rural communities in Malawi. “Development” and “conservation” are all a big, high-stakes experiment, and by studying and evaluating them we may be able to learn something, and become more effective.

A huge expanse of woodlands sprawls across eleven countries of southern Africa, including all of Malawi. Adapted to a climate that is dry for around half the year, and wet and warm for the other half, these woodlands, called “miombo,” range from nearly closed-canopy forests in wetter areas to open wooded savannas with an understory of tall grass in drier areas. Broad-leaved deciduous trees of the legume subfamily Caesalpinioideae are the dominant vegetation in the miombo. In the dry season the leafless trees are grey skeletons with an understory of tawny grass. In the wet season they are lush and green. Miombo trees are adapted to browsing by elephants, and to fires started by lightning or humans, and they are tough and resilient. Many species sprout from roots or stumps if they are broken or burned.

Mature miombo woodland in Nyika National Park

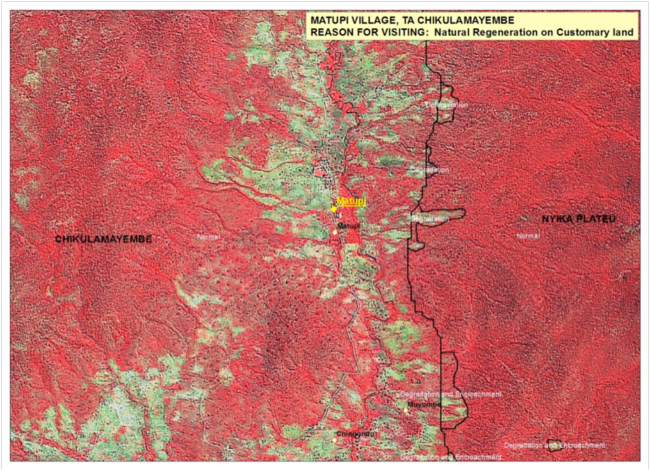

In evaluating the success of the Kulera Project we needed information about the condition of miombo woodlands near villages where the project had been working. Had they been cleared for agriculture, or degraded by tree-cutting for fuelwood, charcoal-making, and construction materials? Had they been recovering due to protection and natural regeneration? We turned to high-resolution, false-color images from the French SPOT 5 satellite, and the remote sensing and GIS specialist working with our team scrutinized SPOT images showing the border zones of all the protected areas where the Kulera Project was working. It was her sleuthing that had led us to Matupi Village.

SPOT 5 image showing Matupi Village surrounded by cultivation, the national park to the east with intact miombo, and well-protected woodland on village land to the west of the village

On these SPOT images, healthy, intact miombo woodland shows up as a textured solid red, indicating lots of structure, leaves, green, and photosynthesis. Crop fields show up as a pale green. On the image around Matupi, the well-respected boundary of the national park was clear, although a few pockets of encroaching agriculture could be seen penetrating into the park. But more striking was that to the west of Matupi on the opposite side of the village from the park, on “customary” land owned and managed by the traditional authorities – the chiefs and village heads – was an area of woodland that from space looked as healthy and intact as the miombo in the park.

We sat in the shade of a big tree and quizzed the Village Headman of Matupi about the situation. A long time ago, a couple of decades at least, he said, the traditional leader of the area saw that people were not “respecting” the woodlands on village land, and they were becoming degraded. So in order to protect all of their values to the village, he began to “protect” them. Here, then, the Kulera Project started working in 2010 in a village that was already conserving its woodlands, and more or less respecting the boundaries of the national park. All the project had to do here was support the traditional leadership and assist an ongoing, grassroots process of conservation.

We visited another village to the northeast of Matupi, called Nkhamayamaji. There, in about 1998, a traditional leader persuaded people to stop cutting trees and allow natural regeneration to take place on the hill above the village, between it and the border of Nyika National Park about five kilometers away. When they weren’t cut and hacked so frequently, the resiliant miombo trees came sprouting back from roots and stumps, and now the hill above Nkhamayamaji is a young woodland with trees up to 20 feet tall and six inches or more in diameter.

Men of Nkhamayamaji Village with regenerating village woodland above them

Before, when the slope was mostly bare, said the village chairman, water would rush down the hill slope into the village, carrying sediment, cutting gullies in fields, washing out huts. Now that doesn’t happen, he said – the water soaks into the woodland on the hill, and fills up the wells down in the village later.

One reason the villagers were persuaded to protect the woodland above Nkhamayamaji, he said, was because of all the wild products they could get from it without having to go into the national park. He mentioned firewood, thatching grass, poles for building houses and tobacco-drying sheds, mushrooms, wild fruits, traditional medicines, and mice and termites for food.

Natural regeneration of woodland protected by Nkhamayamaji Village since 1998

Another miombo “product” is honey. The honeybee, Apis mellifera, is native to the miombo woodlands of southern Africa. It evolved to harvest the pollen and nectar of the multitude of miombo trees that flower. Humans, honeyguides, and honey badgers are some of the species that have coevolved with honeybees in the miombo woodlands. Because of help from the Kulera Project, and previous projects as well, most of the villages we visited had some beekeepers. They place their hives in the mature and regenerating woodlands, reaping a sweet harvest at the risk of some painful stings. Most hives we saw were a modern version of the old, traditional log or bark hives. Some people still gather honey in the traditional way, however, chopping down large trees with honeybee colonies in them, and setting fires to chase away the bees with smoke – a very destructive way to get a bit of honey.

Beehive in miombo

One aspect of the adaptation of miombo woodlands to the periodic disturbance of elephant browsing and fires is that many woody miombo species store a larger proportion of their biomass underground – where it is protected from those disturbances – than would a rainforest or a temperate forest, for example. Because there is a lot of biomass underground, the miombo is extremely rich in fungi – mushrooms – which thrive on that underground carbon-rich food source, often through symbiotic associations with miombo trees. Villagers in Malawi – usually women – gather mushrooms for domestic consumption and for sale. At the end of the rainy season it is common to see them selling bowls of bright orange miombo chanterelles along the roadsides in areas with intact woodland.

Miombo chanterelles for sale by the road

Nkhamayamaji, like Matupi, had started its miombo woodland conservation through traditional, grassroots efforts long before the Kulera Project began in 2010. What Kulera has done is to recognize these successful models of woodland regeneration, and to spread the word, in part by bringing representatives from nearby villages to see what is happening in places like Nkhamayamaji. They have supported the planting of fast growing trees such as Senna siamea in villages, to take some of the pressure off of the native woodlands for construction materials. And Kulera has introduced a new, efficient cookstove design that uses about half as much firewood as the traditional three-stone cooking fire, also reducing pressure on the miombo woodlands both inside of protected areas and on customary village lands.

For more photos of Malawi see: Malawi Biodiversity Projects Evaluation March-April 2013

Related Links:

- Centre for Development Management (CDM)

- ECODIT

- Total Land Care

- Conserving the Miombo Ecoregion. B. Byers. 2001

- Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report. J. Timberlake and E. Chidumayo. 2011

- Ecology and Management of Commercially Harvested Chanterelle Mushrooms

May 6, 2013 1:00 am

[…] For background on the evaluation of USAID-Malawi biodiversity conservation projects in which the village visits described here were made, see: “Restoring Miombo Woodlands for Village Development in Malawi” […]

May 10, 2013 4:15 pm

Dear Bruce,

I wish that I had had a chance to meet you. I was the COP between February 2010 and December 2012 on the Kulera Biodiversity Project working with TLC (Trent, Zwide and Blessings) as well as Washington State University. I am very proud to have been associated with this project and share your assessment that this project did assist in bringing about and or expanding positive change in the project areas. I hope that we have a chance to meet in the not too distant future.

Best,

Mike Whiteman