“The question is not what you look at, but what you see.” Henry David Thoreau

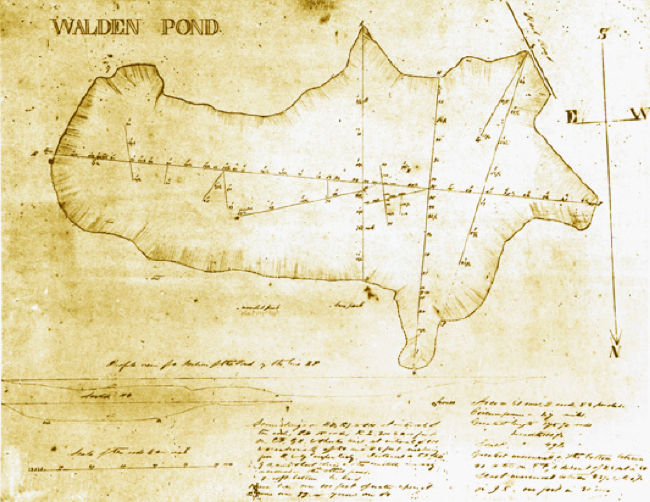

In January of 1846, his first winter in his tiny house by Walden Pond, when Thoreau determined that the ice was finally thick and safe, he undertook a survey to determine the depth of the pond, which had generally been referred to as “bottomless.” He flagged sighting posts along the shoreline and hauled heavy surveying instruments across the ice for a week or two, mapping the perimeter of the pond, then cut more than a hundred holes through the ice with an axe and ice chisel, dropping a plumb line to measure the depth at each point.

Why? Laura Walls, author of the most recent biography of Thoreau, wrote: “It was an extravagant thing to do, wholly impractical. No one needed the pond surveyed, and it took severe study, hard physical labor, and concentrated mathematical skill… to create a remarkable work of art, a working survey that accurately mapped Walden Pond to the inch: length, breadth, and depth.” What Thoreau found, in fact, was that this ice age kettle pond was the deepest lake in Massachusetts, 102 feet deep – but even so, in relation to its surface area, its shape was more like a saucer than a bowl. Nevertheless, his survey led Thoreau to write in Walden that “this pond was made deep and pure for a symbol.” Hmmm… a symbol of what?

In trying to answer that question, it helps to remember Thoreau’s reasons for moving to Walden. One was to observe nature and the world around him directly, transparently, scientifically. Pulled toward the pond four years before moving there, he wrote in his journal “But my friends ask what I will do when I get there. Will it not be employment enough to watch the progress of the seasons?” In his journal after moving to Walden he asked: “What are these pines & these birds about? What is this pond a-doing?” His careful scientific survey of Walden Pond is a clear example of his desire to understand just what was, to get to the bottom of the reputedly bottomless pond.

But, as I discussed in my first essay about my April visit to Walden, for Thoreau living at Walden was also a spiritual quest. When he moved to the pond, “His purpose was profoundly religious,” Walls wrote. Tracing the etymology of the word “religion” leads back to the Latin verb “ligare”: to link, bind, connect, tie. Religion is thus about “re-binding” or “binding back again,” but the question is, to “bind back” to what? For Thoreau, it was to the depths of Walden Pond, to Nature, to bedrock. In that earlier essay I quoted this passage from Walden: “Let us settle ourselves, and work and wedge our feet downward through the mud and slush of opinion, and prejudice, and tradition, and delusion, and appearance, that alluvion which covers the globe, through Paris and London, through New York and Boston and Concord, through Church and State, through poetry and philosophy and religion, till we come to a hard bottom and rocks in place, which we can call reality, and say, This is, and no mistake…” In Thoreau’s Walden dialectic, the pond may be a symbol but it also really has a bottom, 102 feet deep. That’s reality, and no mistake.

——-

The second winter at Walden Thoreau witnessed a new scene on the frozen pond whose depth he had plumbed the winter before. His reaction shows us that he had a very sophisticated imagination of interconnectedness, what he had called “the infinite extent of our relations.” Because the railroad passed so close to the western shore of the pond, a Boston ice company took advantage of the easy transportation to harvest Walden’s ice, shipping it to a global market. In Walden he wrote that “In the winter of ’46-7 there came a hundred men of Hyperborean extraction swoop down on to our pond one morning, …To speak literally, a hundred Irishmen, with Yankee overseers, came from Cambridge every day to get out the ice. … So they came and went every day, with a peculiar shriek from the locomotive, from and to some point of the polar regions, as it seemed to me, like a flock of arctic snow-birds. … Thus it appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and Calcutta, drink at my well. In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvat-Geeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial … I lay down the book and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the … priest of Brahma and Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges.” It is not improbable that British colonial authorities in India were sipping gin-and-tonics chilled with Walden’s ice, so Thoreau’s image of the teleconnections of global trade may not have been so far-fetched.

Much more clear is the extent of global trade in philosophical and religious ideas that was taking place in Concord at the time, with Thoreau at its center. When Emerson took over as editor of the Transcendentalist literary journal The Dial in 1842, he started a regular section called “Ethnical Scriptures,” and drafted Thoreau as its editor. They begin to publish translations from some of the foundational works of Hinduism and Buddhism that were just then arriving in the United States. Some were “discovered” and sometimes translated by British civil servants working in India or Nepal – perhaps some of the same ones sipping their G&Ts on Walden ice. “In 1843 the first copy of the Bhagavad Gita arrived in Concord,” and Emerson at first mistook it for a work of Buddhism, according to Rick Fields, writing in How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America (1992, Shambala Publications). Such was the level of understanding of the great religious traditions of Asia at the time. But in his first winter at Walden, Thoreau was able to read it, and refer to it in his comments about the ice men. In the global trade of the time, ice from Walden was travelling to Asia, and ancient ideas from Asia were finally arriving on American shores.

——-

John Burroughs (1837-1921) was an important figure in American nature writing about whom I’ve written before. Burroughs had a perspective on Thoreau, and Thoreau’s mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson, that seemed always to be somewhat darkened by feeling that he was in their shadow. Interested in local natural history from a young age, Burroughs hoped to become a writer, and he had his first break in 1860 when the Atlantic Monthly magazine published his essay “Expression.” The editor at first thought Burroughs had plagiarized the work from Emerson because it was so similar in tone. A few years before he died, in his eighties, Burroughs began work on a series of essays on Emerson and Thoreau, finally published posthumously in 1922, which show “the abiding importance of Emerson and Thoreau for Burroughs as a literary naturalist and ecocritic,” according to Burroughs’s biographer James Perrin Warren. He was “attempting to interpret the work of Emerson and Thoreau for a new generation,” and emphasized their contributions to ideas about “the place of nature in American culture,” while suggesting that “the new generation was no longer interested in nature writers like him,” and by implication Thoreau.

In the summer of 1883, Burroughs made “a literary pilgrimage to Concord” with his friend Richard Watson Gilder, the editor of Century Magazine, according to Warren. On June 28th, according to Burroughs’s journal, “Gilder & I walk to Walden Pond, much talk & loitering by the way. Walden a clear bright pond, not very wild. Look in vain for the site of Thoreau’s hut… I saw nothing in Concord that recalled Thoreau, except that his ripe culture & tone might well date from such a place.”

Enthusiasm seems distinctly lacking in this cool description, suggesting again that Burroughs wasn’t really a big fan of Thoreau’s work, or perhaps still resented his notoriety. A decade before Burroughs’s visit, other Thoreau enthusiasts were already making their way to Walden and the site of his house there. In 1872, ten years after Henry’s early death, Bronson Alcott guided a Walden fan from Iowa named Mary Newbury Adams to the house site, and they started a cairn just in front of where the door had been, to honor Thoreau’s stay at the pond. Bronson Alcott was a lifelong friend of Emerson and Thoreau, a Concord educator, Transcendentalist, social reformer, abolitionist, and the father of novelist Louisa May Alcott. A tradition was started, and Walden picnickers and Thoreau pilgrims continued to add stones to the memorial cairn. It shouldn’t have been hard to find if Burroughs and Gilder had really wanted to find it.

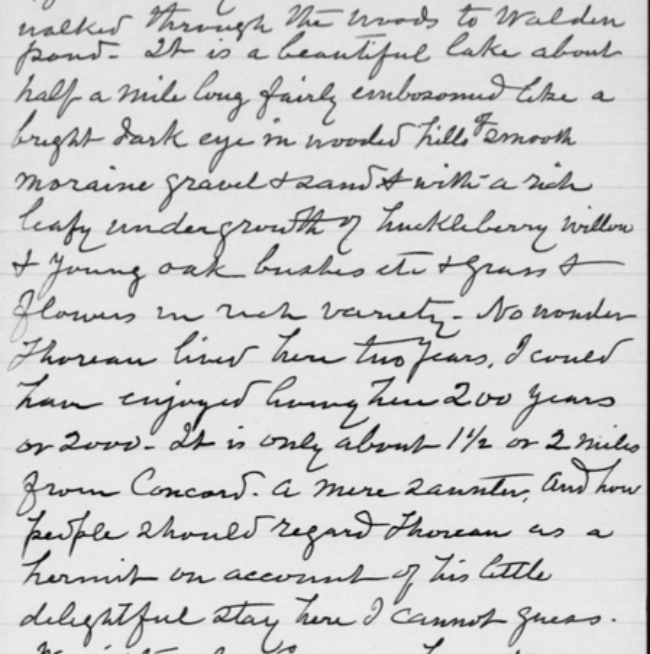

John Muir, Burroughs’s contemporary, had a very different reaction on a visit to Concord. Muir travelled from California to New York in June 1893 and was introduced to many prominent writers and scientists of the day by his editor at Century Magazine, including Burroughs and Gifford Pinchot. On that same trip Muir travelled to Concord, where he was warmly received by Emerson’s son and a Harvard classmate of Thoreau’s. Muir wrote a long letter to his wife Louie on June 12th, 1893, describing some details: “…. we walked through the woods to Walden pond. It is a beautiful lake about half a mile long fairly embosomed like a bright dark eye in wooded hills of smooth moraine gravel & sand & with a rich leafy under growth of huckleberry willow & young oak bushes etc & grass & flowers in rich variety. No wonder Thoreau lived here two years. I could have enjoyed living here 200 years or 2000. It is only about 1 ½ or 2 miles from Concord. A mere saunter, and how people should regard Thoreau as a hermit on account of his little delightful stay here I cannot guess.”

Detail, letter from John Muir to Louie Strenzel Muir, 12 June 1893. Courtesy of John Muir Papers, University of the Pacific

Burroughs and Muir both visited and looked at Thoreau’s Concord, but the two men saw very different things. Muir’s imagination and empathy let him see what he called Walden’s “bright dark eye” and understand what Thoreau saw. Burroughs looked, but “saw nothing in Concord that recalled Thoreau…”

——-

Speaking of looking versus seeing, I ended my last essay, “Wading Into Walden,” with mention of the attacks that Thoreau’s radical ideas attracted in his own day, and even now. Laura Walls says that “No other male American writer has been so discredited for enjoying a meal with loved ones or for not doing his own laundry. But from the very beginning such charges have been used to silence Thoreau.” Some were made by people who weren’t familiar with the geography of Walden and Henry’s life, picturing him as a hermit in the wilderness – an idea that even John Muir knew was silly. His house at the pond was a half-hour walk from his family home in Concord, and if he wasn’t visiting them for Sunday dinner (and having his laundry done there), they were visiting him in his cabin, bringing picnics and news and clean trousers from town.

One of my favorite essayists, Rebecca Solnit, has looked into this puzzling animus towards Thoreau in a clever essay with the wry title, “Mysteries of Thoreau, Unsolved: On the dirtiness of laundry and the strength of sisters,” published in Orion magazine in 2013. Solnit sought out the opinion of Michael Branch, a scholar of early American environmental writing, on this question, and quotes him in her essay: “Better to just say he never did a damned thing except write the century’s best book and leave it at that,” said Branch. After dispensing with the silly and uninformed arguments that Henry was just self-absorbed and helpless, Solnit sums up her high opinion of him with this packed sentence: “Thoreau’s writing helped twentieth-century liberators-Gandhi and King the most famous among them-chart their courses; he helps us chart our own as well, while also helping us measure climate change and giving us the pleasures of his incomparable prose.”

The most blatant recent attack on Thoreau that I discovered was an article from The New Yorker magazine in October 2015 titled “Pond Scum: Henry David Thoreau’s Moral Myopia,” by Kathryn Schulz. I was familiar with Schultz’s writing because of her compelling piece of science journalism and creative nonfiction in The New Yorker about seismology around the Pacific Ring of Fire and the Cascadia subduction zone, “The Really Big One.” I recommend it highly. But wow! Her take on Thoreau was harsh and, I think, a huge misunderstanding of his life, times, and work.

Schultz started her New Yorker piece with a dismissive criticism of Thoreau for his description of a shipwreck in his posthumously published book Cape Cod. ”Who was this cold-eyed man who saw in loss of life only aesthetic gain, who identified not with the drowned or the bereaved but with the storm? This was Henry David Thoreau, that great partisan of the pond, describing his visit to Cohasset in Cape Cod,” she wrote. But Laura Walls, in Thoreau: A Life, read and analyzed Henry’s journal notes from his three trips to Cape Cod, on the first of which, in 1849, he saw the shipwreck he later described, and says Thoreau “was appalled.” Walls calls Cape Cod “Walden’s dark twin,” and says that Thoreau was trying to help us see the powerlessness of humans in the face of nature, while nevertheless conveying a “visceral joy, making this book of darkness blaze with light.”

Schultz wrote that “Walden … like many canonized works, it is more revered than read, so it exists for most people only as a dim impression retained from adolescence or as the source of a few famous lines… Our image of the man has also become simplified and inspirational. In that image, Thoreau is our national conscience: the voice in the American wilderness, urging us to be true to ourselves and to live in harmony with nature. This vision cannot survive any serious reading of Walden. The real Thoreau was, in the fullest sense of the word, self-obsessed: narcissistic, fanatical about self-control, adamant that he required nothing beyond himself to understand and thrive in the world. From that inward fixation flowed a social and political vision that is deeply unsettling.” Schultz claimed that Thoreau “looked down on his entire town,” and that Walden shows him to be a man of “comprehensive arrogance.” But this opinion can’t be based on an open-minded reading of Thoreau, informed by an understanding of his life and times. In his journals and all his published writings his curiosity about life and the human condition reached out so clearly to all of the human and nonhuman inhabitants of his world, and even beyond it to the earlier Native American inhabitants of the place, that it is hard to see how anyone could accuse him of anything but the deepest empathy for all his fellow beings.

As I mentioned in my earlier essay “Wading Into Walden,” Thoreau was a complicated person living in a complicated and contentious era in American history, leading up to the Civil War. Thoreau’s personality – introverted, introspective, contrarian, prophetic – is quite rare, and often misunderstood, and criticized, by the more common “mainstream” personality types – like Schultz?

To quote Thoreau again, “the question is not what you look at, but what you see.” Schultz apparently looked at Thoreau’s life and writing and saw “pond scum.” But “pond scum” is in the eye of the beholder. Like cataracts, some limitations in Schultz’s experience somehow prevented her from seeing a deep and sparkling lake in the landscape of American ideas. It takes some depth to see depth, some sympathy and humility to see genius.

——-

The Concord Transcendentalists, searching for ways to bridge the gap between traditional philosophy and religion and emerging science, were open to many influences. “Transcendentalism, pantheism, and related ideas were all in the air, asserting the unity of spirit and matter and each claiming that it offered the best marriage of science and the imagination,” wrote Donald Worster in his 2008 biography of John Muir. Emerson and Thoreau were certainly somewhat familiar with the Greek and Roman Stoics, whose naturalistic philosophy and ethics must have interested them. They were also familiar with Emmanuel Swedenborg, the controversial Swedish scientist turned mystic, who influenced Transcendentalism. Swedenborg had studied crystal formation and argued that the seemingly-automatic self-organizing patterns generated in crystallization reflected a deeper connection and pattern in nature. Swedenborg used an analogy from the Stoics, writing that nature was like a spiderweb: “For it consists, as it were of infinite radii proceeding from a center, and of infinite circles or polygons, such that nothing can happen in one which is not instantly known at the centre, and thus spreads through much of the web. Thus through contiguity and connection does nature play her part.”

First Parish Church, Concord, 24 April 2018. This Unitarian-Universalist congregation was established in 1636, and attended by Emerson, Thoreau, and most of their Concord families and friends.

The Stoic-Swedenborgian spiderweb is very similar to the Buddhist image of the “Net of Indra” described in the Avatamsaka Sutra. The “Jewel Net of Indra” is pictured as stretching infinitely in all directions, and at each of the knots of the net there is a glittering jewel. All of the other jewels in the net are reflected in each individual jewel, and each jewel reflected is also reflecting all of the other jewels. This metaphor describes what in Pali, the original language of the Buddhist canon, was called paticca samupadda, “dependent co-arising.” Modern Buddhist teachers have called it “interbeing,” or “the harmony of universal symbiosis.” This is a theory of mutual intercausality, interconnectedness, and interdependence. It is a worldview from the same ecophilosophical galaxy as Alexander von Humboldt’s “kosmos,” and the “everything is connected” view at the heart of ecology. When Thoreau wrote that humans need to “realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations,” I imagine he had this kind of idea in mind.

We think in metaphors, often – and even scientists do. Metaphors are the templates of pattern, and having those templates available helps scientists – and everyone – “see” the patterns and relationships underlying the superficial “data” of experience, which often appear pretty chaotic. So, back to Thoreau’s statement in his journal on 5 August 1851 “the question is not what you look at, but what you see.” Seeing deep patterns needs a metaphoric, poetic mind.

Thoreau and his Concord colleagues were not familiar with the Avatamsaka Sutra, but Henry himself was responsible for the first translation of a Buddhist text published in English. As the editor of the “Ethnical Scriptures” section of The Dial, he was always on the lookout for exotic spiritual and philosophical texts, and sometime in 1843 he found an article, in French, by Eugene Burnouf, a Paris-based scholar of Pali and Sanskrit. It was a translation from Sanskrit of the Saddharmapundarika Sutra, or “Sutra of the Lotus of the Good Law,” one of the fundamental scriptures of Mahayana Buddhism, which had been sent to him by a British government official posted at the court of Nepal. Having learned French (and several other classical and modern languages) at Harvard, Thoreau translated the introduction to the Lotus Sutra from Bernouf’s article, and it was published as “The Preaching of the Buddha” the January 1844 issue of The Dial. It is an interesting coincidence that a central part of the sutra Thoreau translated is a parable about a blind man, who, when told that “there are diversities of color and spectators of these diverse colors; there is a sun and a moon, and constellations and stars, and spectators who see the stars, the man born blind believes them not, and wishes to have no relations with them.”

It is hard to know how much his exposure to Buddhism influenced Thoreau’s thinking, and how much of what he found in the Lotus Sutra simply resonated with his own personality and intuitions. I think it’s mostly the latter. Rick Fields explores this question a bit in in How the Swans Came to the Lake, his history of Buddhism in America. “The Concordians were at odds with their age, and they looked to the Orientals as an example of what their own best lives might be,” says Fields. Thoreau himself wrote: “…. There is an orientalism in the most restless pioneer, and the farthest west is but the farthest east.” Fields points out that Thoreau’s “nature was always that of a contemplative,” and reminds us that in 1841 Thoreau wrote in his journal that “I want to go soon and live away by the pond, where I shall hear only the wind whispering among the reeds. It will be a success if I shall have left myself behind.” It’s not hard to imagine those lines coming from a Zen monk.

For Thoreau, moving to Walden was also an attempt to experience and dwell in the present moment, to seek a kind of temporal “bedrock” reality. “God himself culminates in the present moment, and will never be more divine in the lapse of all the ages,” he wrote in Walden. In other words, heaven ain’t somewhere else, its here and now. This is a worldview completely familiar to Buddhism. How did Thoreau get there? According to Fields, “One might say that Thoreau was pre-Buddhist in much the same way that the Chinese Taoists were…. That is to say, he was perhaps the first American to explore the nontheistic mode of contemplation which is the distinguishing mark of Buddhism.” Thoreau, in some way, seems to have been such a psychological and philosophical experimentalist that he discovered, from a base in the worldview of his Unitarian and Transcendentalist culture in Concord, the same truths that Siddhartha Gautama discovered in 500 BCE India from his base in the worldview of his princely Hindu culture. They both touched the same universal human bedrock. Thoreau cracked all of the koan, the zen-riddles-with-no-answers, in his meditations. Nature and his neighbors, apparently, were his sensei, his teachers.

——-

Muir was deeply moved by visiting the graves of Emerson and Thoreau. In his long letter to Louie of 12 June 1893 he wrote: “Went through lovely ferny flowery woods & meadows to the hill cemetery & laid flowers on Thoreaus & Emersons graves. I think it is the most beautiful graveyard I ever saw it is on a hill perhaps 150 feet high in the woods of pine oak beech maple etc. & all the ground is flowery Thoreau lies with his father mother & brother not far from Emerson & Hawthorne. … the soil he sleeps in is glacial drift almost wholly unchanged since first this country saw the light at the close of the glacial period. There are many other graves here though it is not one of the old cemeteries. Not one of them is raised above ground. Sweet Kindly mother Earth”

The posture taken by Siddhartha Guatama, the historical founder of Buddhism, after a night spent in meditation under the “bodhi tree,” or tree of enlightenment, wrestling with all the “demons” that Mara – goddess of illusion – could conjure up and throw at him, was to reach down with his right hand and touch the ground, showing that he would not be moved – that he was touching reality, touching bedrock, touching the earth, touching truth. Thoreau touched the earth at Walden too. He was a prophet, trying to bind us back to bedrock by asking us to see “the infinite extent of our relations,” to see and touch “Sweet Kindly mother Earth,” as Muir called her. Henry’s blazes along the Walden trails still can help show us the way to do that.

For related stories see:

- Wading Into Walden, April 2018.

- A Walk on Wachusett, April 2018.

- The Great Tidepool and the Stars, August 2017.

- Another Visit with John Burroughs at Slabsides, May 2016.

- An Afternoon at Slabsides with John o’ the Birds, May 2015.

Sources and related links:

- “The question is not what you look at, but what you see” – source of quote

- Walden Pond survey drawing. H.D. Thoreau, 1846. Concord Free Public Library

- Henry David Thoreau: A Life. 2017. Laura Dassow Walls. U. of Chicago Press.

- Laura Dassow Walls wins Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Thoreau biography. Notre Dame News, 30 April 2018.

- Walden and On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. Full searchable text PDF. WW Norton.

- How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America. Rick Fields, 1992. Shambala Publications.

- John Burroughs and the Place of Nature. James Perrin Warren, 2006. U. of Georgia Press.

- John Muir Correspondence – 1893. John Muir Papers, University of the Pacific Digital Collections.

- Mysteries of Thoreau, Unsolved: On the dirtiness of laundry and the strength of sisters. Rebecca Solnit. Orion magazine, May/June 2013.

- Mysteries of Thoreau, Unsolved. Rebecca Solnit. Orion, 2013. Full scanned text PDF.

- Pond Scum: Henry David Thoreau’s Moral Myopia. Kathryn Schulz. The New Yorker. October 19, 2015.

- The Really Big One. Kathryn Schultz, 2015. The New Yorker, July 20, 2015.

- Cape Cod. H.D. Thoreau, 1866. Free PDF download.

- Toward an Ecocentric Community: from ego-self to eco-self. Bruce Byers, 1992. Turning Wheel.

- Salmon in the Net of Indra: A Buddhist View of Nature and Communities. Fred Allendorf & Bruce Byers, 1998. Worldviews: Environment, Culture, Religion 2: 37-52.

- The Rain of Law: Thoreau’s Translation of the Lotus Sutra. Wendell Paiz, 1992. Tricycle.

- Why the Buddha Touched the Earth. 2011. John Stanley and David Loy. The Blog, Huffington Post.

June 15, 2018 4:27 pm

Bruce –

Thanks much for these thoughts on HDT. Imagine if he had had access to the practice of still sitting, but perhaps, as you say, he cracked the koan through the touch of Mother Earth.

Appreciate your views of the contrast between the two Johnnies, your handling of Ms. Schultz, and your nod to Rebecca Solnit. Poor David Henry, how sadly misunderstood; curious that two of his most sympathetic readers are women (Solnit and Walls).

“Our whole life is startlingly moral.” HDT