March 2014. Almost exactly three years ago, in March, 2011, serendipity handed me the opportunity to lead a biodiversity conservation assessment for the U.S. Agency for International Development in Ukraine, and I worked with a team of exceptional Ukrainian consultants. The dramatic recent developments in Ukraine have turned my thoughts back to that unforgettable experience. I walked across the Maidan in Kiev many times on that trip, where recent news photos showed burning barricades, molotov flames, and bloody demonstrators barely a week ago. My concern led me to contact Alena, Galina, and Oleksiy, my team members, for firsthand news. All were fine, but seemed shaken and scared.

The Maidan in March 2011: Ukraine’s Independence Square, site of “Orange Revolution” demonstrations in 2004-2005, and demonstrations and violence in 2013-2014.

Ukraine. I had heard of it of course, and knew it was a breadbasket and industrial heartland of the former Soviet Union. But biodiversity in Ukraine? As far as I knew no one thought of it as a biodiversity “hotspot.” But it was paying work, and so I went. What an eye- and mind-opening experience it was!

A bit of background first. In an amendment to the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 – Section 119, enacted in 1987 – Congress imposed a mandatory “Country Analysis Requirement” on the U.S. Agency for International Development related to the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity – wild species and natural ecosystems. Before developing a new strategy or program for development assistance in a country, USAID had to conduct an assessment to identify threats to biodiversity in that country, and determine how proposed USAID activities would help to address – or possibly add to – those threats. The amendment was meant as an environmental safeguard to prevent any more ecologically-insensitive US development aid, some of which in the past, by funding roads through tropical forests, dams on untamed rivers, irrigation projects in critical wetlands, and many other unscrutinized actions in the name of “development,” had probably helped to cause the extinction of dozens of species and the cutting of thousands of hectares of forests. Because of this legal requirement, USAID-Ukraine was legally obligated to conduct an FAA Section 119 Biodiversity Assessment. Enter Alena, Galina, Oleksiy, and I – we were the assessment team – working under a contract through the small consulting firm Ecodit. Alena is a conservation biologist, Galina an aquatic ecologist, and Oleksiy a botanist.

Field site visits to check out the situation on the ground are a typical part of these assessments, and USAID had asked us where we thought we should go to learn about biodiversity conservation challenges in Ukraine. In our proposal we suggested western and southern Ukraine, but when we talked to the USAID staff, they shifted the compass points of our geographic plan. We know pretty well what people in western Ukraine think, they said, and the south has been over-emphasized too. But we really don’t understand what people in eastern Ukraine are thinking, they said. Is there any biodiversity there? If so, what about going east, over near the border with Russia, to check it out for us? Sure, why not, we agreed. We bought our plane tickets from Kiev to Donetsk.

That was my first clue that Ukraine is a linguistically, and also politically, polarized country. My Ukrainian colleagues on the assessment team educated me over the course of our work together. Eastern Ukraine is the coal mining and industrial region, and the agricultural breadbasket of the country. Its people identify with Russia, and Russian is the predominant language.

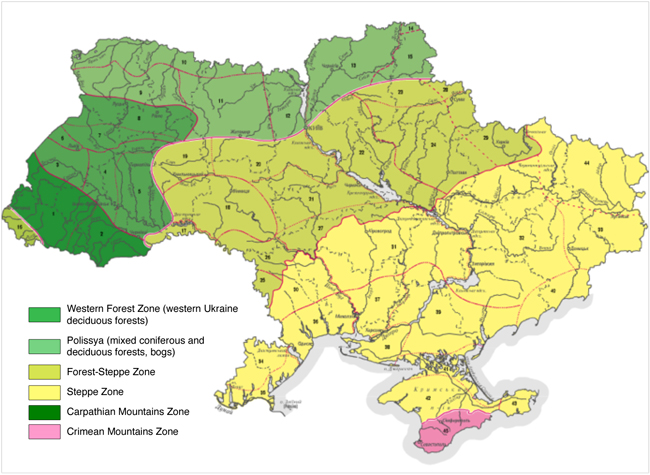

An ecological map of Ukraine shows an uncanny resemblance to the linguistic map. Ecologically speaking, the Russian part of the country is the heart of the steppe – the grassland ecoregion that corresponds to our midwestern prairies in North America. Grasslands worldwide are among the most threatened natural ecosystems, because they have mostly been converted to agriculture, whether in the U.S. or Ukraine. Their unique biodiversity is a threatened global treasure. Oleksiy, our team botanist, had been involved in an initiative to conserve the Ukrainian steppe, perhaps the most threatened ecosystem in the country.

We landed late at night on March 28th, and at 11 PM checked into the small, cozy Hotel Dominik, with colors and patterns and a stylish sense of design that gave it a strange 1950s feel. A quiet snow fell in the night, a couple of inches by morning. We had meetings with the Head of the Nature Protection Service of Donetsk Oblast, and the Director of the Donetskiy Krazh Regional Landscape Park. After our meetings we drove north to the park and wandered a bit in a hypothermic fog with the park staff.

And here, wandering the wet cold grassland, Oleksiy spotted a clump of wild crocus, Crocus reticulatus, blooming. Pale blue-purple petals, and in the center, yellow pollen-bearing stamens and three orange stigmas. This species is sometimes called wild saffron, the wild relative of the crocus whose stigmas are harvested to produce saffron, the spice. This species is in the Ukrainian Red Book of threatened and endangered species. Ukrainian steppe haiku:

Unexpected on

this cold steppe day finding the

wild crocus blooming

And birdsong… familiar, but from where? Ah, yes, I’d heard it before, long ago in the spring on the English moors: the Eurasian skylark, Alauda arvensis. We spotted a singing male – fluttering high, twittering, twittering, twittering, a glorious waterfall of notes, then plunging, silently, back to the wet cold ground. Even wrapped in bone-chilling rain and near-freezing fog, spring sprung in my heart at that moment.

Skylark! Between black

chernozem earth and white

cold fog, your song opens

a space for spring

After lunch we drove on north to Lugansk, capital city of another “oblast,” or administrative region. The next day, March 30th, was all sun and blue sky, all the more welcome in contrast to the previous day. It was a day of the colors of Ukraine’s flag, a top panel of deep sky blue, and bottom panel of yellow like sunflowers, or golden steppe. We drove backroads to the west and north of Lugansk in mud season, through small dying villages next to closed coal mines.

Surreal mountains of tailings from the coal mines of this region were scattered everywhere across the rolling steppe landscape like volcanoes. One was smoking, a coal fire smoldering underground near the top. All day the views out across the landscape, rolling on a huge scale. I don’t know where in North America I’ve seen this big a big sky landscape. The closest thing I remember is eastern Montana, western North Dakota, along the Missouri before it breaks south, the old Mandan country.

Steppe volcano; coal fires smoldering in mine tailings of closed mine near Noholniy Krazh, Lugansk Oblast, eastern Ukraine

The patches of remaining unplowed steppe were mainly on the ridges – the crags, or “krazh” in Ukrainian and Russian – where the land fell away to the villages and coal mines and towns and black chernozem fields below. Late in the afternoon, after meeting with a village mayor, we drove up and over Naholniy Krazh, the largest remaining intact area of steppe vegetation in Ukraine, completely unprotected by the regional and national system of nature reserves. Sixteen species found in this area are in Ukraine Red Book of threatened and endangered species. Oleksiy said this was his “favorite place in Ukraine.” He had once seen wild wolves here, he said. I didn’t know whether to believe him or not. I wanted to.

A few more wild saffron, this time opened in full bloom in the warm sun by the side of the soggy snowmelt road, their pale blue-purple almost like a pasqueflower’s. And the larks again! The larks ascending, into the blue sky, trilling and trilling and trilling their exuberant, irrepressible, endless song, reminding me of mockingbirds in spirit but surpassing them in musicality. Rising and circling above their territories on the dry steppe that we mere mortals walked so far below, pouring down their spring blessings on us, a rain of holy music, clearing winter and cold out of our ground-bound souls.

Crocus reticulatus, wild saffron, a species in the Ukraine Red Book of threatened and endangered species

We found lots of Cetraria steppe, a lovely, wine-colored fructicose lichen that is a steppe indicator species, and also listed as threatened in the Ukraine Red Book.

Cetraria steppe, the steppe lichen, at an unprotected site on Naholniy Krazh, Lugansk Oblast, eastern Ukraine

Stained glass window of Lenin in the main entrance of the State Agency for Nature Protection, Lugansk Oblast

Unprotected and overgrazed site on Naholniy Krazh; Alena photographing Cetraria steppe, the endangered steppe lichen, mountains of coal-mine tailings on the horizon

Driving back toward Lugansk at the end of a long day, the sun sinking into the layer of coal smoke haze lying above the black land and getting redder and redder, we listened to Bob Marley on a CD from the eclectic music collection of the driver we had hired to take us on this field site visit, who turned out to be an Azerbaijani immigrant. It’s a small, strange, endlessly fascinating world, isn’t it?, I thought.

The steppe. The grasslands of Eurasia stretch from Mongolia to Ukraine. In 1240, Mongol horsemen led by Genghis Khan’s grandson Batu attacked and sacked Kiev, capital of the kingdom of the Kievan Rus, founded by Scandinavian Vikings from the dark boreal forests of the north, which had flourished here for more than three centuries. It was centuries before it started to lean back again toward the forest-oriented cultures to the north and west. Located in an ecotone – an ecological transition zone – of continental scale, Ukraine has been a landscape contested between forest and steppe species and cultures for millennia.

The “Arab Spring” seemed at first so full of promise and hope. But in several countries across the Arab world, its manifestation has exposed deep contradictions between the desert-adapted Islamic Arab mind and what some people from cultures from more temperate climes think of as “spring.” I’m hoping that in Ukraine, a political “spring” really is coming, followed soon by the crocuses on the steppe, and the pussywillows in the forest wetlands, a blooming of natural and human possibilities long overdue in this culturally and ecologically complex and contested land.

See more pictures:

Related links:

March 10, 2014 4:30 pm

Again Mr. Bruce, Thank you very much.Glad to hear from you.Victor

March 11, 2014 1:53 am

Great trip. The steppe lichen is amazing. The grazing photo is over-the-top. It takes a lot of moving sheep to get it down that close.

On our front lawn (in Arlington, VA, USA), we have hundreds of individuals of a crocus species that is a dead ringer for C. reticulatus. I don’t remember a network pattern on them (which the species name suggests). But they are (photographically) identical to your picture.

Thanks again, Rich

March 11, 2014 8:11 pm

Nuevamente me alegro saber de ti. Gracias por informarnos sobre este bello país y sobre tu experiencia en esa nación; por lo que he podido percibir me da la impresión que realizasteis un excelente estudio y que contribuyo muchísimo en USAID Programs relacionados con el manejo de RRNN y Biodervidad. Lamentamos mucho lo que esta pasando con nuestros hermanos Ukranianos, nos solidarizamos con ellos y que Dios los proteja.

Abrazos Bruce from Choluteca Honduras

March 12, 2014 4:39 am

Thank you Brucer for sharing that wonderful experience. I hope someday I can visit this beautiful country. Rosa Mercedes Escolán

March 13, 2014 3:01 pm

Hi Bruce,

It’s really opening up the mind to see, and to read something about the Ukraine which is not totally tainted by power-struggle, cold war language or worse. It’s good to see that there are also normal people and even nature present in Ukraine.

February 11, 2019 7:17 pm

[…] La steppe-forêt (vert clair) juste avant la steppe du sud-est http://www.brucebyersconsulting.com/ukrainian-spring […]