March 22, 2021. It was a beautiful morning as I drove west on I-66 and turned north toward Sky Meadows State Park. From the Crooked Run Valley, the meadows sweep up to the old farm and on toward the ridge to the west, along which the Appalachian Trail runs. The parking lot beside the visitor center in historic Bleak House, built of local stone in the early 1840s, had only a few cars. It had been a decade or more since I’d been out here, and I only half-remembered the place, like next-morning images from a dream. Across a gentle valley below the farm were rows and rows of evenly spaced white objects that reminded me of gravestones. I didn’t remember them from my long-ago visit, but this was Confederate territory after all, and maybe I’d forgotten that there was a Civil War cemetery here.

There was no sign of the group of volunteers from The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) who were supposed to be gathering here to plant chestnuts this morning. I called Pete, the organizer, on his mobile phone from mine; he coached me to look west across the gentle valley below the house and barn to where a couple of pickups were parked along the edge of that “cemetery.” I walked in that direction for a quarter mile or so along an old tree-lined road with a snaking stone wall of blue slate until I got to a gate in a tall deer-proof fence with a sign for the “Sky Meadows American Chestnut Orchard.” What had appeared to be gravestones turned out to be white plastic collars placed around chestnut seedlings to protect them until they got bigger.

Pete met me by his pickup, the back stuffed with bags of peat planting mix, fiberglass stakes, and protective plastic sleeves. I was soon at work with half a dozen other volunteers, pounding stakes at one-foot intervals along straight rows laid out in plots previously marked with red- and blue-flagged markers, and digging fist-sized holes beside each stake.

During a brief break for a drink of water, I asked Pete, a retired systems-engineer, how he got so deeply into this project. “Oh, my daughter gave me a book about the American chestnut a few years ago, and it was really interesting. After reading that, I contacted The American Chestnut Foundation, and one thing led to another… and here I am, coordinating volunteers and taking care of this orchard.” The book to which he was referring is American Chestnut: The Life, Death, and Rebirth of a Perfect Tree, by Susan Freinkel (University of California Press, 2009).

Down at the far end of the newly-ploughed field was a white pickup, and a solitary figure was measuring and flagging the area and making notes on his clipboard. He would occasionally holler up to one of the other men about the layout of the new area. Curious about everything, I asked Pete what was happening. He explained that Fred, the guy with the measuring tape and flagging, was in charge of all of this. He called him their “chief scientist.” “Really?” I said, “Then I need to talk to him!” When I finally did, and he introduced himself, I realized this really was the chief scientist of The American Chestnut Foundation, Dr. Fred Hebard. Now retired, he masterminded their chestnut breeding program at Meadowview in southwestern Virginia since its beginning 1989. When I joked with him that he must be doing this just for fun, spending these long days planting chestnuts after retirement, he came back with “Just for fun, or something like that.” A video of Fred describing the breeding program can be found here.

The scientific story behind all of this is a bit complicated, but here it is, in a nutshell: As I described in more detail in my story A Decade of American Chestnut Restoration on Timber Lane, the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) once ranged from Maine to Mississippi, and from the Atlantic Coast to the Ohio Valley, with the heart of its range in the Appalachian Mountains, where it was an ecologically dominant forest tree. But around 1900 a parasitic fungus called Cryphonectria parasitica was inadvertently introduced to North America on nursery stock of Asian chestnut species; the fungus spread rapidly and killed most American chestnuts. The fungus is found naturally in Asia, and Asian chestnuts have coevolved with it and are not very susceptible to the chestnut blight. American and Asian chestnuts are quite closely related, in an evolutionary sense, and hybridize when grown together. This hybridization potential was the cornerstone of The American Chestnut Foundation’s breeding program.

The program was first conceptualized by Charles Burnham, a plant geneticist from the University of Minnesota, who had worked extensively with maize. He proposed, in 1981, that backcross breeding probably could be used to transfer blight resistance from the Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima) to the American chestnut.This conclusion was based on earlier research that appeared to show that there were two partially-dominant genes for blight resistance in the Chinese trees that had been used as parents in earlier crosses with American chestnuts. The breeding process envisioned for chestnuts was similar to what Gregor Mendel, the simple Austrian monk whose experiments with garden peas set the stage for modern genetics, would have used if he wanted to have only purple-flowered, wrinkled peas: crossing parental generations and selecting the offspring that carried the desired genetic traits.

Burnham proposed beginning with three generations of “backcrossing” hybrids between American and Chinese chestnuts. Genetically, the initial interspecific hybrids should carry one-half American chestnut genes, and one-half Chinese. In the first backcross generation, those hybrid trees would be crossed with American chestnuts, concentrating American chestnut genes and diluting the Chinese genetic contribution; the offspring of that cross should get, on average, three-quarters of their genes from American chestnuts and one-quarter from Chinese. Those trees would be screened for both blight resistance and American chestnut traits such as a straight, tall growth form; cold tolerance; nut sweetness; and competitive ability in forest plantings. The most blight tolerant and “American” offspring were then crossed back with American chestnuts, producing a second backcross generation that was genetically seven-eighths American and only one-eighth Chinese. Those were again screened and again backcrossed, producing a third backcross generation with fifteen-sixteenth American genes—on average more than 90 percent—and only one-sixteenth Chinese, but including the blight-resistance genes. When that third backcross generation, designated BC3, is crossed, some of the progeny should be highly blight resistant. They should have mostly American chestnut genes and traits, but genes for blight resistance should be concentrated. The idea was that those trees would then be planted in seed production orchards, where further screening and selection would produce seeds suitable for restoration of chestnuts in natural forests. That, at least, was the idea—and still is, in general, with a few updates.

From the beginning it was recognized that this kind of interbreeding and selection using hybrids of two wild species was different than working with maize or other domesticated crop plants. In order to retain the genetic variation of original, wild populations of American chestnuts, which had allowed them to adapt across a wide geographic range, a large number of pure American chestnut individuals had to be used as parents in each backcross generation.

TACF’s 1999 scientific review of the first decade of the breeding program noted “new insights and problems that have arisen,” including some genetic incompatibilities that affect hybridization between American and Chinese chestnuts (i.e., although they hybridize easily, they don’t do so perfectly) and some apparent genetic defects carried in the genotypes of some trees, which cause dwarfing and deformed bark. An external science review of TACF’s chestnut breeding work by a panel of five scientists in 2018 reinforced the message of how difficult and complicated a process it is to breed a blight-resistant American chestnut. The panel recommended that TACF “complete its evaluation and progeny tests of the best backcross materials in a focused and rigorous manner, but given that blight resistance levels and tree form appear to be short of hopes for this stage of the program, consider reducing investment in these materials in the future in favor of investments in the infusion and rapid breeding with new sources of genetic diversity.” They also recommended continued exploration of genetic engineering options, such as the incorporation of the OxO blight-resistance gene, and combinations of the backcross-breeding and genetic modification strategies. The review also noted the need for further research on chestnut silviculture, establishment of scientific field trials, and release of the best seed lots for restoration.

The genetic challenges of a breeding strategy to develop blight-resistant American chestnuts are detailed in a 2017 article, “Rescue of American Chestnut with Extraspecific Genes Following it Destruction by a Naturalized Pathogen,” by Kim Steiner and colleagues (Fred Hebard was one of the six coauthors). A paper in Evolutionary Applications by Jared Westbrook and colleagues (2019) had the subtitle “A Trade‐off with American Chestnut Ancestry Implies Resistance is Polygenic,” and concluded that “On average, selected BC3F2 trees inherited 83% of their genome from American chestnut and have blight resistance that is intermediate between F1 hybrids [between Chinese and American chestnut] and American chestnut.” The American Chestnut Foundation summarizes their breeding work in this way: “During the past 36 years, offspring from blight resistant hybrids have been bred with American chestnuts from across the species’ range. Four generations later, our traditional breeding program has produced a genetically diverse population of American chestnut hybrids with improved blight tolerance from Chinese chestnuts (Castanea mollissima).” Reality, in other words, has proven to be bit more complicated than envisioned in the original Burnham model for the breeding program, which has nevertheless been important and successful.

The American Chestnut Foundation now has sixteen chapters ranging from Maine to Alabama. These chapters have mobilized volunteers and are currently selecting the most blight-resistant hybrids in seed production orchards across the American chestnut’s native range, a critical step in ensuring that the hybrids are well-adapted to local environmental conditions. These orchards will eventually provide regionally adapted blight-resistant seed for restoration. The Sky Meadows site is one of fourteen such seed production orchards developed and maintained by the Virginia Chapter of TACF.

_______

When we had staked and dug hundreds of holes, we stopped for lunch; after lunch it was time to plant. I followed Fred to the end of a row, where he handed me a plastic bag of moist peat in which chestnuts from last fall’s crop from TACF breeding orchards in northern Virginia had been “stratified”—kept cold and moist to trigger their germination after a winter rest. There were maybe fifty nuts in the bag, most with roots sprouting from their tips, anywhere from a nubbin to a few inches long. Fred patiently showed me how to fill the holes we’d dug in the morning with a peat planting mixture to give the seeds a weed-free early nest, how to set them in, and how to snug the protective collars down around them. I didn’t know much about Fred Hebard then, but now I do after learning about his work and reading many of his papers—and so I now realize how special it was to be taught to plant these tender seeds by the scientist who has spent his career creating the hope that they represent.

Fred sent me the report of the spring 2021 planting efforts in northern Virginia recently. Almost 3,000 chestnut seeds were planted at Sky Meadows by volunteers over three days of work, and almost 2,000 more at two other seed orchards maintained by the TACF Northern Virginia chapter. My contribution to the total was puny, but I’m happy to have contributed to the effort.

_______

What I’ve been describing is one of the ways chestnut scientists and restoration enthusiasts are working to put the American chestnut back into our forests—the “how” of it, if you will. But what about the “why” of it? What motivates us to want to restore a lost species and recreate historical ecosystems that have disappeared because of human actions? And what are the moral and ethical issues involved in trying to do that?

A friend nudged me to pay more attention to these dimensions—the psychological, emotional, philosophical aspects—of chestnut restoration when he responded to my blog A Decade of American Chestnut Restoration on Timber Lane last September. He wrote: “I’m a bit ambivalent about bringing American chestnuts back by continual diluted hybridization with Asian chestnuts — not enthusiastic about that, but not willing to carry a picket sign against it. While it’s true that we’ve altered nature for the worse, I don’t see that an argument for trying to alter nature for the better with our puny understanding of its wisdom. I’m much more in favor of pulling back, accepting the damage we’ve done, appreciating what’s left, and working to restore nature—if we can—by replanting trees, releasing non-genetically-altered animals and plants where they once lived, etc.” He was especially critical of the idea of using genetically engineered American chestnuts carrying the OxO gene that gives them blight resistance in restoration efforts. But he has planted some pure American chestnuts in his yard—not the triple-backcross hybrids that my neighbor and I have—hoping (against hope?), I guess, that his little chestnuts will be able to hide out in the DC metropolitan area and not be found by Cryphonectria parasitica because of the low density of American chestnuts here.

When I realized I wanted to learn and think more about the ethics of chestnut restoration, I quickly fell down a fascinating rabbit-hole. It turns out that environmental philosophers have been thinking hard about this. An American Chestnut Foundation webinar, titled “Exploring Big Questions for American Chestnut Restoration, was my entrée to this wonderland of ecological-restoration ethics. Evelyn Brister, a professor of philosophy at the Rochester Institute of Technology and one presenter in the webinar, laid out the ethical arguments: “What are the moral concerns and motivations?” she asked. She was mainly focusing on the proposed use of the genetically engineered OxO chestnut in restoration, but her questions seem to me to be relevant for the TACF backcross-bred chestnuts also. “Would using these human-modified trees make the forest less natural? Less wild? Are we able to anticipate and manage the potential ecological risks—the possible unintended consequences—of reintroducing these trees? And are we motivated by a properly respectful and humble attitude toward nature?”

Hmmm! Big questions in several different dimensions. In starting to answer the first one, “is it natural,” it’s clear that the functional extirpation of the American chestnut is the result of human actions, and our chestnut-less forests are therefore not natural—unless you want to say that our inadvertent introduction of exotic pathogens, is “natural” too. It seems to me, though, that is too late to worry about the ethical issue of “naturalness,” because the forests are already unnatural, at least in an ecologically historical sense. The question of “wildness” gets a little more subjective and complicated, so although very interesting and worth thinking about (see Clare Palmer’s paper listed in sources below), I won’t try to get into that here.

As an ecologist, the risk of unintended ecological consequences is one of my main concerns when I think about humans mucking around with complex natural systems with inadequate knowledge. What about that, with regard to reintroducing backcrossed near-American-type chestnuts? The answer, I think, is research. We should be able to anticipate the possible ecological consequences through appropriate research, and if we apply the “precautionary principle,” and don’t do something unless we are pretty damn sure we understand the consequences, then we should be able to safely surmount that practical ethical barrier.

Then we come to Brister’s final question: Are we motivated by a properly respectful and humble attitude toward nature? What are our intentions? Are we doing this out of a sense of wanting to benefit nature, and also future human generations? Can we use restoration of the American chestnut as a way to “grow a sense of care, a community of care, to repair harm, to produce something of value to future generations?” she asked.

What is the “big picture” context of our actions to restore the American chestnut? And would the ethics of our actions differ if seen in the light of the Western philosophical tradition—Aristotelian virtue ethics, for example—versus the ethical perspective of a different worldview, such as Buddhist “Net of Indra” ethics?

I find that I keep coming back to ask the question about meaning. What happens ecologically isn’t as important—for me at least—as what happens psychologically to us as we try to help, save, protect, restore, or “rewild” a place, or “de-extinct” a species. Even if the TACF seed production orchard at Sky Meadows succeeds, producing wheelbarrow- and pickup-loads of chestnuts suitable for restocking the hills above these meadows with not-quite-but-almost American chestnuts, the other volunteers and I from that sunbaked dusty day won’t see the results. That will take generations, at least. But we can imagine them: Chestnuts towering along the ridge, under which hikers on the Appalachian Trail will walk; which will feed deer, turkeys, bears, and squirrels; and some of those chestnut-fattened species in turn may even support wolves and mountain lions again someday.

We can imagine, and hope, and therein lies the satisfaction and the meaning that planting these sprouting backcrossed chestnuts at Sky Meadows gives us. The hope fills up the hole created by the feeling of something lost, something noble and good and priceless that is missing. It feels like paying a debt owed to this ecosystem; reconciliation with an unintended but awful consequence of our forebears’ ecological ignorance; a virtuous act, a quest for redemption of sorts.

For related stories see:

Sources and other links:

- Sky Meadows State Park

- Sky Meadows Bleak House Visitor Center Video Tour

- Freinkel, Susan. 2009. American Chestnut: The Life, Death, and Rebirth of a Perfect Tree. University of California Press.

- Video interview with Dr. Fred Hebard, “The Blight Resistant Chestnut Tree,” 2018

- Nash, Steve. “A Man and His Tree.” The Washington Post, July 25, 2004.

- Ray, Kimber. “Dr. Fred Hebard: Resurrecting the American Chestnut.” The Appalachian Voice, October 13, 2014.

- The American Chestnut Foundation. 1999. Science Review.

- The American Chestnut Foundation. 2018. External Science Review.

- Steiner, Kim C., et al. 2017. “Rescue of American Chestnut with Extraspecific Genes Following its Destruction by a Naturalized Pathogen.” New Forests 48: 317-336.

- “American Chestnut Rescue Will Succeed, But Slower Than Expected.” Science Daily, May 16, 2017.

- Westbrook, Jared W., et al. 2019. “Optimizing Genomic Selection for Blight Resistance in American Chestnut Backcross Populations: A Trade‐Off with American Chestnut Ancestry Implies Resistance is Polygenic.” Evolutionary Applications.

- Jacobs, Douglass F., Harmony J. Dalgleish, and C. Dana Nelson. et al. 2013. “A Conceptual Framework for Restoration of Threatened Plants: The Effective Model of American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) Reintroduction.” New Phytologist.

- Exploring Big Questions for American Chestnut Restoration, TACF “Chestnut Chat” webinar, 19 March 2021.

- Brister, Evelyn, and Andrew E. Newhouse. 2020. “Not the Same Old Chestnut: Rewilding Forests with Biotechnology.” Environmental Ethics 42: 149-167.

- Palmer, Clare. 2016. “Saving Species but Losing Wildness: Should We Genetically Adapt Wild Animal Species to Help Them Respond to Climate Change?”

- Newhouse, Andrew E., and William A. Powell. 2020. “Intentional Introgression of a Blight Tolerance Transgene to Rescue the Remnant Population of American Chestnut.” Conservation Science and Practice.

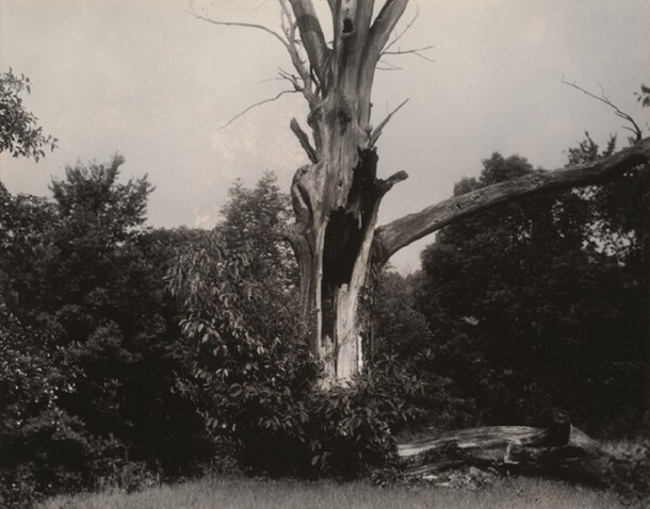

- Stieglitz, Alfred. Dead Chestnut Tree, probably 1937. National Gallery of Art.

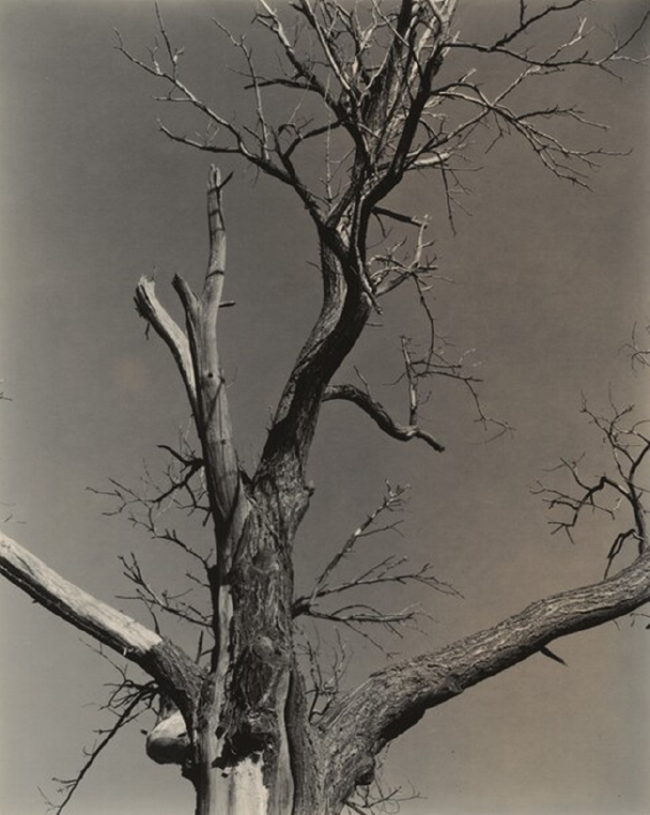

- Stieglitz, Alfred. The Dying Chestnut Tree, 1927. National Gallery of Art.

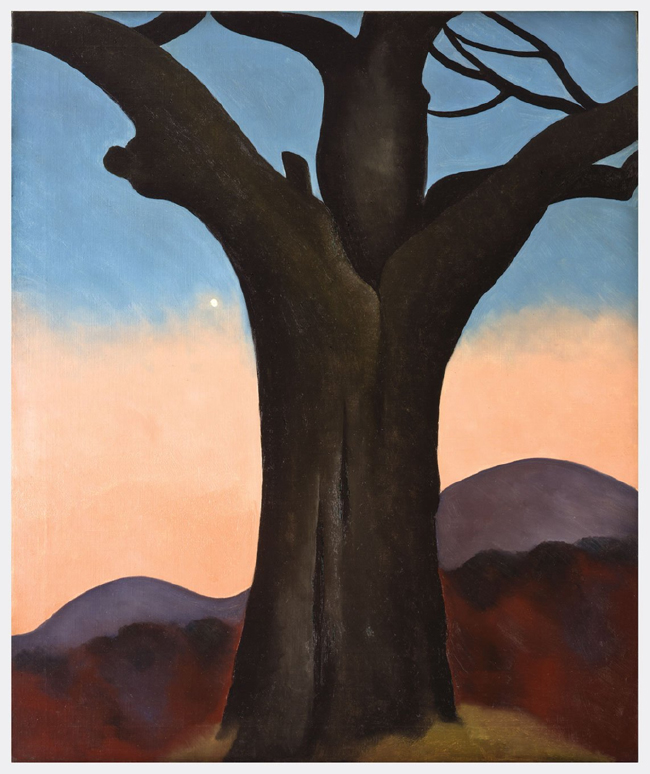

- O’Keeffe, Georgia. The Chestnut Grey, 1924. Curtis Galleries, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

- Hursthouse, Rosalind, and Glen Pettigrove, “Virtue Ethics”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).