On my recent “book tour” to the San Francisco Bay Area to talk about and promote my book Nature on the Edge: Lessons for the Biosphere from the California Coast, I had planned to stay at the UC Berkeley’s Point Reyes Field Station. But those plans fell through suddenly and unexpectedly when I arrived at the historic ranch house that serves as the research station, and found I’d be sharing it with a film crew from UC Santa Cruz, there making a film about someone I’d never heard of. The communal space we’d have to share was filled with their gear and chaos, and I saw in a second it was not going to work out. I bailed, and shifted to lodgings I knew of in Mill Valley, which had a view northwest across the Richmond Bay salt marshes to Mount Tamalpais.

With that serendipitous change of plans, for more than a week I shared a bedroom with the mountain. Enough time to initiate an intimate relationship. I saw her just before sleep, and first thing in the morning. I got to know some of her many moods, all alluring. It would take a lifetime, or several, to know them all. Others have been seduced by her charms, many others. Some of them, artists, recorded her moods in their works. I snapped photos on my iPhone.

The name Tamalpais is from the Miwok language of the most recent Indigenous inhabitants of the area, and means roughly “west hill.” Besides being a topographical landmark in their home territory, it was a mythical and spiritual landmark too. After all, Old Man Coyote sat up there on Mount Tamalpais one day—a long time ago, they say—and created the world and everything in it, where we live today.

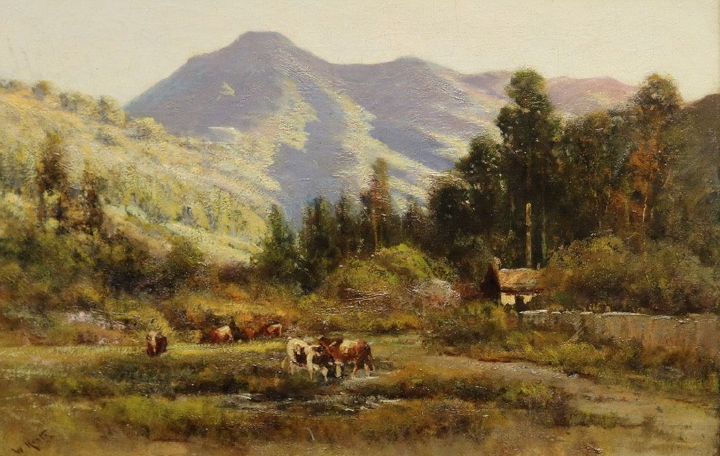

California landscape painter William Keith had a serious relationship with Mount Tam. Born in Scotland in 1811, Keith immigrated to the United States and found himself in San Francisco in 1859. Just after the Civil War, in the later 1860s, he was already painting Yosemite and other locations in the Sierra Nevada. His timing overlapped with John Muir, whose book My First Summer in the Sierra described his wanderings in those mountains in 1869. The two Scotsmen eventually became fast friends, and Keith’s art supported Muir’s conservation efforts by publicizing the “sublime” beauty of Sierran landscapes. I think of Keith as a western member of the Hudson River School of American landscape artists—Thomas Cole, Frederick Church, Thomas Moran, and Albert Bierstadt, as exemplars—all using art to glorify American nature and resist its destruction by the wave of “Manifest Destiny” washing westward from the industrialized east. Keith’s first painting of Mount Tam dates to 1870, when he painted A Broadside of Mount Tamalpais, showing the mountain rising in a mostly natural but pastoral landscape. The painting now hangs in the De Young Museum in San Francisco.

The mountain continued to exercise her power over the burgeoning San Francisco Bay area in the last decades of the 1800s and into the 1900s. In 1907, William Kent purchased the forested canyon of the main southern watershed of Mount Tamalpais, Redwood Creek, and created Muir Woods National Monument, honoring John Muir, through his skillful political maneuvering, He and his wife worked to protect more of the mountain through the creation of the Mount Tamalpais State Park. Part of their interest in nature protection was economic; a decade before Muir Woods, Kent built a scenic tourist railway from Mill Valley to the top of East Peak and promoted scenery-oriented tourism. The railroad operated until 1930.

A new chapter in the relationship with the mountain opened in October,1965, when three Beat poets—Gary Snyder, Allan Ginsberg, and Philip Whalen—made a ritual walk up and around the mountain from Muir Woods to the East Peak and back—a “circumambulation”—modelled on similar spiritual pilgrimage practices in the Buddhist and Hindu traditions in Asia, meant to acknowledge and sanctify a place or landscape. They promoted the circumambulation in 1967 at the “Human Be-In” in Golden Gate Park, and eventually the practice caught on among a small but dedicated group of adherents, who now conduct the ritual circumambulation four times a year on the solstices and equinoxes.

As I planned my book-tour trip, I chose September 21st, the Fall Equinox, as a date to anchor the schedule of events, because I wanted to participate in the circumambulation again. I had joined the group of “circumTambulators” on the Summer Solstice in 2021, and wrote about it in the essay in the book titled “Circling the Mountain.” I arrived in Mill Valley the afternoon of September 20th and watched the sun set over the mountain. The next morning, I joined the group at Muir Woods to chant the Heart Sutra at the two-plank bridge crossing Redwood Creek and begin the walk.

Tom Killion was born in Mill Valley in 1953, with Mount Tamalpais in his backyard. While a student at UC Santa Cruz, Killion learned the art of woodblock printmaking, and in 1975 published 28 views of Mount Tamalpais: Sky, Earth, Sea. His title played off of the famous series of prints, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, by Japanese woodblock master Hokusai, made from1830 to1832. Killion has continued to produce woodcuts of Mount Tam, many of which are included in a 2009 book, Tamalpais Walking, made in collaboration with Gary Snyder.

(Ah! Almost the view from my room!)

And now to the subject of the film being made by the UC Santa Cruz filmmakers whose chaos had chased me from the Point Reyes Field Station: Lebanese-American artist and poet Etel Adnan—the person I said at the beginning I’d never heard of. You may not have heard of her either; when I learned more about her, I wasn’t surprised that I had not. But it turns out that she had and still has something of a cultish following in the San Francisco Bay Area—hence the film-making expedition. Born in Beirut in 1925, of Turkish, Greek, and Albanian ancestry, Adnan had a complicated life; she moved to France and studied in Paris just after World War II, then at Harvard and UC Berkeley, and eventually taught at the Dominican University of California in San Rafael. San Rafael is just north of Mill Valley, where Mount Tamalpais dominates the western skyline. She developed a deep, obsessive relationship with the mountain, which she reflected in a trove of vibrant paintings.

I will be waiting for the documentary about Adnan that was in the making and created the chaos at the Point Reyes Field Station, which chased me away and changed my lodging plans; and made time for a brief affair with Tam that showed me some of her many lovely moods.