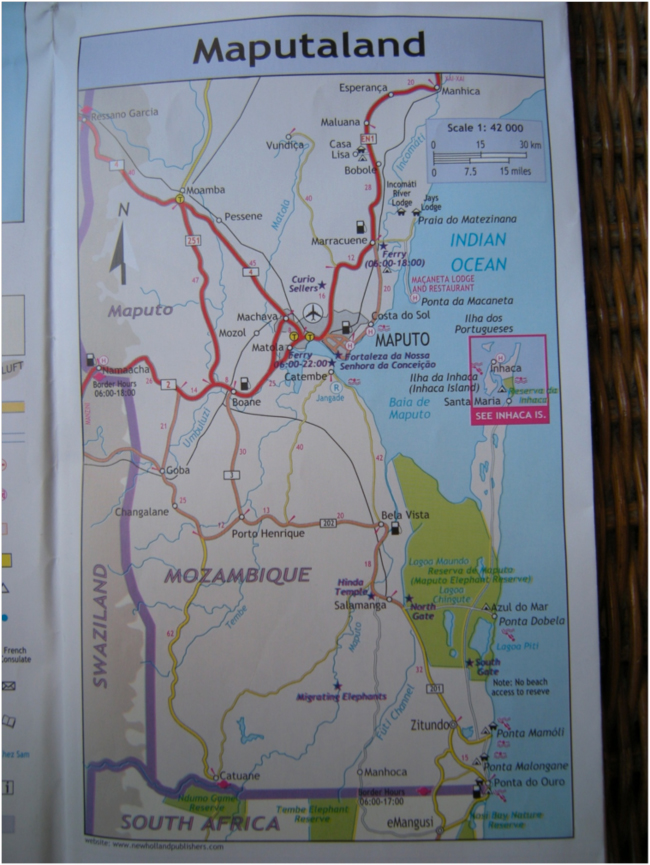

14 September 2012. We drove onto the small twelve-car ferry just before 6:00 AM on a Friday morning, heading across Maputo Bay for Catembe past the brightly lighted docks under grey dawn skies. It was already starting to sprinkle a little. The forecast was for rain, to last through the weekend. The road south was slow, part rutted sand, part old pothole-pocked pavement that was even slower than the sand. By 9:00 we were at the headquarters of the Maputo Special Reserve, on time for a meeting with Armando Nguenha, manager of the Peace Parks Foundation project working in the reserve, and Rodolfo Cumbane, the project’s ecologist.

Sitting around a small conference table in the headquarters office, one big room under a high thatched roof with a few desks, some laptops, and dimly lit with a few fluorescent tubes, we learned about the status of the reserve, its growing population of resident elephants – estimated at around 400 now – and the challenges of managing the area. After the meeting, driving south through the reserve, we saw no eles, only their dung along the road. A lot of poaching went on here during the seventeen-year civil war, which ended in 1992. Elephants live long lives, and at least some of those that survived the war still carry bad memories of people with guns. They are skittish and aggressive – a sign at the entrance to the reserve included a warning graphic of an elephant charging a vehicle.

We were rushing to Ponta do Ouro to meet Miguel Gonçalves, Manager of the Ponta do Ouro Partial Marine Reserve, by noon. The reserve is designated as “partial” to indicate, in the terminology of Mozambique’s protected area system, that it is not totally off limits to any human uses except perhaps scientific research and education – so not a “complete” reserve. In fact, it is a multiple-use area, with artisanal fishing communities, clusters of beach homes, sport fishing, and various kinds of nature-based tourism such as scuba diving and “swim with the dolphins” adventures. The beaches of the peninsula stretching from here to the tip of the Machangulo Peninsula at the mouth of Maputo Bay roughly 100 kilometers north are the most important leatherback and loggerhead turtle nesting habitat in Mozambique. Leatherbacks, the largest sea turtles, are classified as critically endangered globally, and loggerheads are endangered.

The biggest threat to the Marine Reserve, Miguel said, was a plan to develop a giant new port facility at Ponta Techobanine to export coal from Botswana to China. The development would cut through the biggest coral reef in the reserve, through coastal dunes, and into Lake Piti, one of the freshwater coastal lakes at the edge of the Maputo Special Reserve.

At the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro three months ago, held twenty years after the landmark 1992 conference and so called “Rio+20,” the President of Mozambique, Armando Guebuza, officially launched something called the “Green Economy Roadmap.” President Guebuza stated that this “roadmap” will allow Mozambique to become “an inclusive, middle-income country by 2030, based on the protection, restoration and rational use of natural capital and ecosystem services, to guarantee inclusive and efficient sustainable development, within planetary limits.” The President emphasized that working together “to save the earth and its biodiversity is an imperative. It is an ethical duty, a moral obligation.”

When I mentioned this to a Mozambican we interviewed, he just laughed. He said he didn’t see much evidence that the government was trying to do anything serious about many of the country’s environmental problems. The Chinese are building a huge new cement plant along the sand road leading down the peninsula south of Maputo that we drove to reach Ponta do Ouro. They are planning to build a bridge across Maputo Bay to reach the planned port facility at Ponta Techobanine that Miguel loses sleep over. The big “buzz” in the country right now centers on the recent discoveries of huge offshore fields of natural gas in Cabo Delgado Province in the north – said to be the largest in the world; of coal in Tete Province in the northwest; and offshore oil as well. Texas-based Anadarko Petroleum Corporation, and ENI, an Italian energy company, are about to invest $50 billion in Cabo Delgado to develop the offshore gas, we were told.

We spent the night in a simple, clean, sheltered guest house, “A Lar da Ouro,” tucked into the trees on the high sand ridge that rises from the beach north of the rocky point. Waves of rumbling thunderstorms passed at intervals and dumped hard rain, unusual and early for September according to my colleagues. Rain frogs sang exhuberantly in the palmy garden during the downpours.

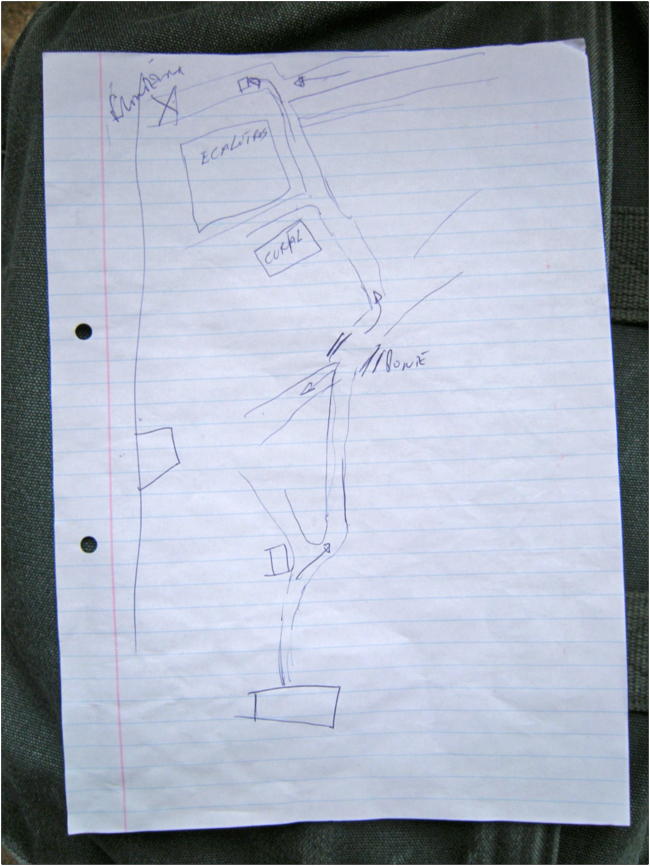

The next morning we planned to drive to a medicinal plants market that happens every Saturday in Phuza, a village at a now-closed border crossing between Mozambique and South Africa west of Ponta do Ouro. Marcos, who was driving our team’s rented 4X4 Toyota Prado, didn’t know the way to the place, so we drove down to the boat-launching site on the beach, where Filemón, a local who worked for the Marine Reserve, was supervising the launching of sport-fishing boats. Filemón drew us a crude map on a sheet of paper, with a few landmarks: a house, a powerline, a “ponte,” a “coral,” and a Eucalyptus plantation. He sent us off with a cheerful “it’s easy to find,” and we headed into the grey morning with the expectation that we’d be at the market in half an hour or so. We took what Marcos thought was the right sand road, following the powerlines past the airstrip, and taking the forks indicated on the map. In about twenty minutes the road veered away from the powerlines, and we found ourselves at a dead end in a sand pit where someone had been digging and hauling sand for local construction. It was drizzling gently by now.

We backtracked, and spotted a woman walking in a field, so we stopped and Felisbela called for her to come over. She had a digging stick and a bag full of roots, gathering wild medicinal plants in the rain, her clothes soaked. She pointed us off on another sand road, and we finally spotted a house. Good! We’re back on the map, we thought. But just to confirm the route from here, we pulled up to the house, where a man was standing in the doorway. We gestured that he should come over to the car, so he got out an old umbrella and came over. Yes, yes, he said, it’s that way – pointing up the road. Will the medicinal plants sellers be there, in this rain? my colleagues asked him. “Oooh! Of course!” he said, laughing at such a silly question, adding something that roughly translated as “money talks louder than rain.” We still weren’t completely convinced that the plant sellers would be there, but we didn’t have any other hot options, so decided that we might as well give it a try, since it was close.

After another twenty minutes or so the sand road dimmed and turned to a track among old fields. It didn’t look like we were heading in the right direction for the river or the bridge. But in the distance we saw a white twin-cab pickup moving along a road – they must be local, they must know where they are going, we thought. Follow them! We found our way back to another fork in the road, and took the track they must be on. Sure enough, soon we saw the white truck up ahead. But we caught up too quickly, and saw that they were stuck in deep sand on a hill. They were white South Africans, lost, without 4-wheel-drive, and were overjoyed to see us and be unexpectedly rescued. They hooked up some thin nylon webbing to our vehicle as a makeshift tow rope, and by pulling very gently with our vehicle in 4-wheel-drive, Marcos was able to tow them out.

We had been travelling for well over an hour now, and still didn’t really know where we were, but there were few options left, so we headed up a road we had not yet travelled, and in another twenty minutes got to the bridge. This was finally, once again, a place Marcos recognized, and was on Filemón’s trusted map! We drove on, and sure enough, there was a corral, and a Eucalyptus plantation in the distance. We saw two boys herding cattle in yellow rain slickers, and asked them how to get to the medicinal plants market. They pointed down the left hand fork of the road. Although our map showed us taking the right hand fork, we trusted this “local knowledge” – and anyway, we must be close. Our map showed the Phuza market just on the other side of the Eucalyptus plantation, so if we didn’t find it going this way, we could easily come back and try the other road.

We drove another twenty minutes. No plant market. Another twenty minutes. We must be close, let’s keep going. Another twenty minutes. We spotted a building, headquarter of a cattle operation. Marcos asked the men standing out of the rain on the porch, and they said that Phuza was back the way we had come about a half hour’s drive, and then another half hour down another road. We had been driving for three hours since leaving Ponta do Ouro, and it was now late morning. Not knowing what we would find even if we found the place, we decided to turn around and head back north toward Maputo.

I remembered the story they told me in Muzarabani, in Zimbabwe, about the hunters who came looking for elephants in the area of the sacred forests I was studying there in 1997. They had gotten a permit to hunt on these communal lands from the District authorities, who assured them there were plenty of elephants. But they had driven for days, scouting, and had seen no sign of elephants. Finally they went to the chief of the area to complain that they had been misled about elephants here. His first question was whether they had paid a visit to the traditional religious leader, the spirit medium, to ask permission to hunt. They hadn’t, needless to say. So they were instructed in the proper protocol, and they went to the spirit medium with gifts of cloth, tobacco, some money, and a little local rum. In a day or so they had found and shot their trophy elephant.

Maybe the medicinal plants market was happening today. Maybe it was close to Ponta do Ouro, as we had imagined. But we never managed to find it. Maybe the spirits of the territory were hiding it from us. We hadn’t consulted them, only our map.

What we found instead was a big, sandy, scarcely inhabited savanna landscape, crossed by unmarked sand roads, with patches of trees here and there, but mainly open, with scattered bushy palms. In a few places the palms had grown into low trees, with single trunks maybe 30 feet tall, but those were the exception. The reason, my colleagues said, is because this palm species, Hyphaene coriacea, sometimes called the Ilala Palm, is used to make “uchema,” a local palm wine. At the right season the growing tip of the palm is cut, and the flowing sap is tapped and fermented. According to a report published by MICOA, Mozambique’s Ministry for the Coordination of Environmental Affairs, “Uchema is a vital part of the area`s economy. Many households produce and cell [sic] palm wine regularly. Palm wine is not only produced by many households but also it is produced in large quantities.” This was uchema territory, and uchema was not one of the landmarks on our map. We had been lost all morning, but we had seen a lot of territory.

The phrase “the map is not the territory” first appeared in a paper presented in 1931 by Alfred Korzybski, a Polish-American mathematician, at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in New Orleans. Korzybski was trying to make the point that many people confuse models or concepts or mental representations with reality itself, but this is a philosophical error. However, as a mathematician, whose work was to make mental abstractions of the way things relate together, Korzybski surely understood that although “the map is not the territory,” and equations are not nature, maps can help us find our way and equations can convey patterns in complex phenomena. (The sunlight lying across the lawn as I write is not E=mc2, but the equation nevertheless describes something real about it.)

The Chinese are commonly blamed in Mozambique for the rampant poaching of elephants and illegal cutting of high-value hardwoods like ebony and sandalwood. Shark fins and sea cucumbers are flowing to China from Mozambique’s coasts and reefs. Locals call it the “Chinese takeaway,” using the British-English term for carry-out food. In this case, a “takeaway” of Mozambican living natural resources is already well advanced, and its fossil fuel resources will soon be flowing to Asia also. A giant presidential mansion is rising on the bluff near the hotel where I’m staying, gift – of guess which country?

Meanwhile, other donors, like USAID, are interested in helping Mozambique cope with climate change – sea level rise and potentially more devastating cyclones, floods, and droughts. And also helping Mozambique protect its forests, including coastal mangroves, to suck up and store carbon from burning all those fossil fuels. The race is on – and fossil fuels are winning. Stopping the development of one coal mine, coal-export port, or one new gas field in Mozambique would do more to prevent global warming than all the REDD and “climate change adaptation” projects that foreign donors and pie-in-the-sky environmentalists could dream up. But they aren’t flashing $50 billion dollars like Anadarko and the Chinese. The “green” in President Guebuza’s “Green Economy Roadmap” right now seems to be the green of the “greenback” dollar; coincidentally, the Chinese one yuan bill is green too.

After driving for hours without really knowing where we were going, it seemed time to turn around, and head home. The “green economy,” like the medicinal plants market, may really exist, be we can’t find it with this map. Maybe we can try another day, in better weather, with more information, more local knowledge, on another trip. Maybe we should consult the spirit mediums first.

Gregory Bateson, in his 1972 book Steps to an Ecology of Mind, argued that we can never really “know” the “territory”: that anything we can really know about reality is only some representation of it in our minds. But, no worries, no problem, really. “Bateson points out that the usefulness of a map (a representation of reality) is not necessarily a matter of its literal truthfulness, but its having a structure analogous, for the purpose at hand, to the territory,” according to Wikipedia. To follow Bateson’s metaphor, maybe what we are searching for here is the “ecosystem” – the system of relationships and emergent properties – that connects the mind with the landscape, the internal “map” with the external “territory.” After all, in the conceptual vision of ecology everything is connected to everything else, so there is really no “internal” and “external” anyway. It’s all part of the territory.

Click here to see more photos from this trip!

Related Links:

- Peace Parks Foundation, Lubombo Transfrontier Conservation Area

- Ponta do Ouro Partial Marine Reserve Management Plan

- Techobanine Port

- Mozambique Green Economy Roadmap

- Offshore Natural Gas, Cabo Delgado

- Anardarko World Petroleum

- Hyphaene coriacea, Ilala Palm

October 3, 2012 12:54 pm

Thanka a lot Bruce for sharing this wonderful experience with us. It looks like you keep very busy all around. Good for you. If you are ever in this part of the world, please let me know. Froylan

October 13, 2012 1:28 pm

[…] our unsuccessful attempt to find the medicinal plants market in Phuza, near Ponta do Ouro (see The Map Is Not the Territory blog), the forest expert on our assessment team, Mario Falcão, promised to take me to Xipamanine […]