When Spanish explorer Juan Cabrillo sailed into the Santa Barbara Channel in 1542, he found a thriving indigenous maritime culture living along the coasts and on the Channel Islands. One thing that impressed the Spaniards were the large seagoing canoes. One major coastal village had so many canoes on the beach that Cabrillo called it “pueblo de los canoas.” The Chumash name of the town was humaliwo, “where the surf sounds loudly”; now the place is called Malibu, echoing the Chumash name, and is known as a surfing mecca. Farther west along the coast Cabrillo noted a village where canoes were being manufactured, and he therefore called it “Carpinteria” (meaning “carpentry”) in Spanish; the modern city, between Ventura and Santa Barbara, is still called Carpinteria.

Cabrillo had encountered what has been called a culture of “complex hunter-gatherers” (Gamble, 2008, p. 276) that managed to support one of the densest populations of any non-farming group of Native Americans at the time Europeans arrived. Chumash society was more complex and sophisticated than many other hunter-gatherer cultures in many ways. Traits associated with this sociopolitical complexity include permanent settlements of considerable size; storage of large amounts of food, such as acorns and fish; environmental manipulation, especially the use of fire, to promote desired species; occupational specialization; social hierarchy; extensive political and economic alliances; and complex technologies (Gamble, 2008, p. 276).

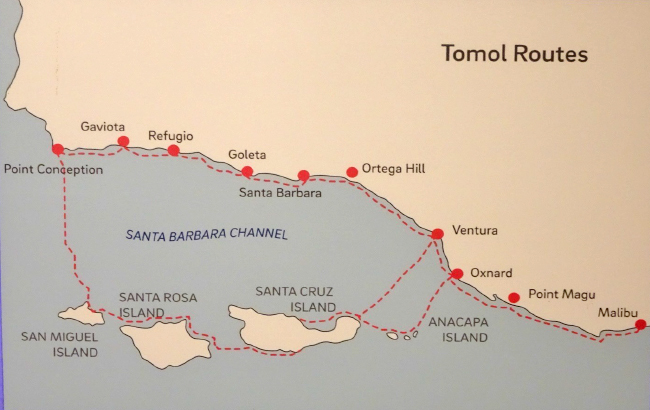

The tomol, the most technologically sophisticated watercraft in indigenous North America, was the keystone technology of the society and economy of the Chumash. It linked the marine and terrestrial ecology of the culture, enabling regular cross-channel travel for social, economic, and ceremonial purposes, and for trade of foods, raw materials, and finished products. From the mainland, foods such as acorns (and acorn meal) and seeds, animal skins and furs, milkweed and dogbane fibers for making twine, and asphaltum (natural petroleum tar) for caulking tomols were traded for island specialties such as soapstone, redwood driftwood for making tomols, otter pelts, finished products of marine mammal bone and shell, and shell beads. Eventually the production of shell beads for trade focused on Santa Cruz Island, and these came to be used as a form of money throughout the area. Trade across an ecoregion with both terrestrial and marine components may have enabled the development of the advanced hunter-gatherer society the Spanish encountered half a millennium ago.

The word chumash originally meant “makers of shell bead money,” and Santa Cruz Island, the hub of the production of shell beads, was called mi’chumash, “the place where they make shell bead money,” throughout the region—except by the inhabitants of the island themselves, who called it limuw, “in the ocean.” So, the name “Chumash” given to the indigenous communities of the California Bight and islands is something of a misnomer; it is an “exonym”—a generic name given by outsiders, not used for their own communities by those people themselves (Hoppa and Vestuto, 2020).

The tomol is a type of sewn plank canoe, found only among the Chumash and the Tongva, their neighbors just to the south. It is not known when the Chumash invented or acquired this canoe technology, which is a unique boat type on the Pacific Coast. Similar sewn plank canoes are used in Polynesia, and some people have proposed that the Chumash acquired the technology from Polynesian voyagers who visited the Channel Islands sometime in the last several thousand years (Wiener, 2013). The nearest indigenous seagoing canoes on the Pacific Coast were dugout canoes, used by groups living north of Cape Mendocino almost 500 miles north, such as the Yurok of the lower Klamath River, who carved their canoes out of single redwood logs. Boats made of bundles of tule, the giant wetland sedge (Schoenoplectus acutus), were used by Central Valley tribes and those of the San Francisco Bay area, but their fragility and water-logging propensity has led many experts to doubt that they were seaworthy enough to cross the Chumash Channel. The oldest human remains found on the Channel Islands are more than 13,000 years old, and even then, with sea levels much lower than today, the distance between the islands and the mainland was five miles or so, so the first humans on the islands must have had some type of seaworthy watercraft.

Redwood was the preferred wood for tomols, although Douglas-fir or pine were sometimes used. Although the nearest redwoods grow just south of San Francisco Bay, the California Current often carried redwood logs that washed out of northern California rivers to the shores of the outer northern Channel Islands. The Chumash name for what is now called Santa Rosa Island was Wi’ma, “driftwood,” apparently because it was a prime location for finding redwood for tomol-building.

_______

I had read and heard about the Chumash tomol before visiting the area in October, and I wanted to learn more and see these boats up close. My first chance came at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, where the first attempt to revive the traditional design and methods of tomol-building is displayed. It sits just below the ceiling in a dimly lit room containing other artifacts of Chumash culture. The feeling it conveyed was of a sad, dried fish out of water. But the story of this particular tomol is inspiring, reaching right to the roots of the restoration and revitalization of Chumash culture and language.

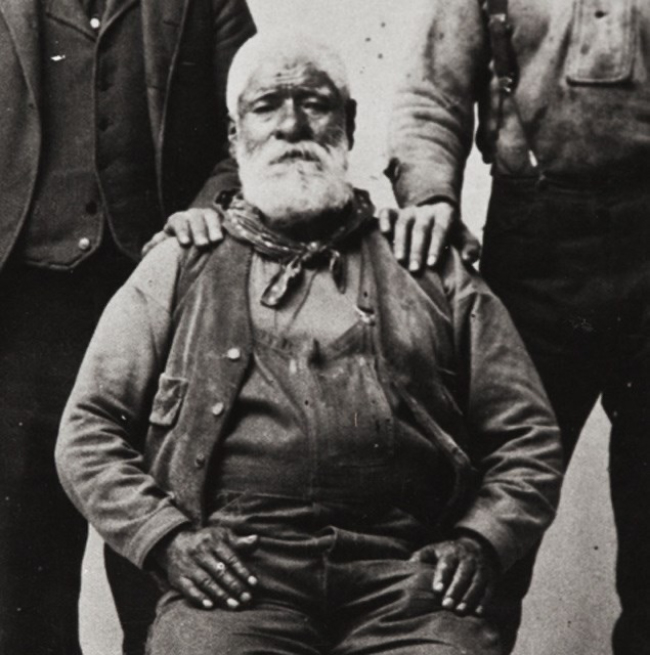

I’ve mentioned many times already in these blog essays that one of the lessons from the Cascade Head Biosphere Reserve in Oregon is that “people matter,” and this forlorn tomol is a wonderful illustration of a person whose life made a difference in our ability to understand and restore some of Chumash culture. Fernando Librado, who also used his Chumash name Kitsepawit, was born in 1839 at the San Buenaventura Mission to parents from Santa Cruz Island who had been moved to the mission some 25 years earlier.

The last Chumash tomols were being built in the 1850s. Librado had seen the process as a young man, and also heard descriptions from older Chumash who had been members of the canoe building and paddling guild called “The Brotherhood of the Canoe.” He became one of the most important linguistic and ethnographic informants of anthropologist John Peabody Harrington (more on him in a moment). Harrington persuaded Librado to build a tomol for display at the Panama–California Exposition, which was held in San Diego from 1915 to 1917 to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. Working from memory, Librado directed the construction beginning around 1912, when he was 73 years old. He did not attempt to use only traditional methods and tools. Harrington recorded the process in scrupulous notes. This is the canoe now displayed at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

Harrington’s notes and Librado’s tomol were the foundation for the modern era of tomol building and voyaging. In 1976, the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History and the Quabajai Chumash Association of the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation used their model and information to build a full-sized tomol, named Helek (“falcon” or “peregrine falcon” in Chumash), which was tested at sea around several of the northern Channel Islands. Many more tomols have followed.

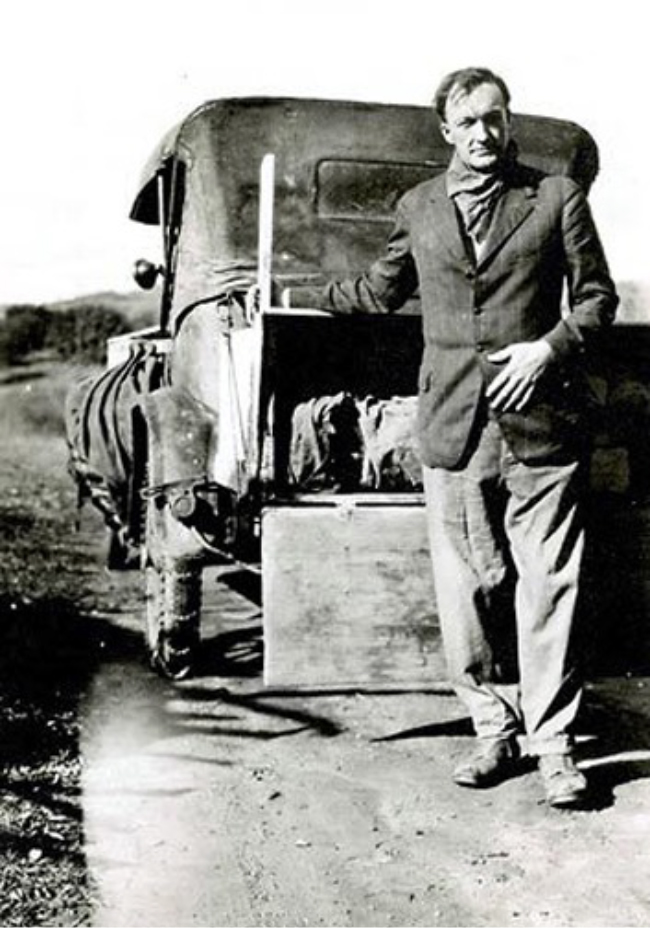

Kitsepawit’s accomplice in capturing the last memories of tomol technology was an American anthropologist, John Peabody Harrington (1884-1961). “Few scholars can claim to have saved an entire culture from historical oblivion. John Peabody Harrington was one of those,” wrote Brian Fagan in his book Before California (p. 329). Harrington grew up in California and began undergraduate studies at Stanford University in 1902, majoring in anthropology and classical languages. He took a summer class at UC Berkeley from Alfred Kroeber, the first graduate student and protégé of Franz Boas, who was just beginning his lifelong study of California Indians. “Kroeber’s lectures electrified Harrington,” Fagan wrote, and Harrington began his lifelong study of the languages and cultures of southern California, focusing especially on the Chumash.

“For Harrington, the preservation of the Chumash languages was a labor of love which bordered on obsession. He did most of his work between 1912 and 1922, when there were still some fluent speakers of Chumash left. Although it had been well over a century since the arrival of the missionaries, a few of Harrington’s informants were able to recall a great deal of what they had heard of the old people and their ways. In particular, Maria Solares of Santa Ynez and Fernando Librado of Ventura furnished valuable linguistic and ethnographic information.” (Applegate, 1974, p. 187)

Harrington’s “labor of love which bordered on obsession” also made possible the reconstruction of something much less tangible than the tomol: the worldview of the Chumash. Based on his diligent ethnographic recording of the stories, legends, and myths of his Chumash informants, Thomas Blackburn attempted to do that in his book December’s Child (1975). This is such a rich and important story that I can’t explore it here, but will in an essay to follow.

_______

I mentioned seeing the tomol built by Librado Kitsepawit at the Santa Barbara Natural History Museum to a Chumash contact who, it turned out, was a tomol paddler himself. Tomol are sea creatures, he said; they are stranded and sad if not in or near the ocean. I asked him where I could see a modern, living tomol, perhaps even one that had been involved in the crossings to the islands that I’d read about and seen in videos. “Go to Arroyo Burro,” he said.

So I went on a quest to Arroyo Burro Beach, a Santa Barbara County park. West of the parking lot and beach access at this tucked-away and locally popular little beach is the Watershed Resource Center, and on its public deck are photos and informational signs about the recent history of tomol building and voyaging. On the ground level, in a securely fenced area, a large dark tomol rested on a trailer, as if ready to be pulled to the beach and to slide off into the water. I guessed its length to be about 25 feet. The inlaid design on its bow, what looked to me like a golden dolphin in a ring of leaping dolphins, must signify its name, but I couldn’t find pictures or other information to identify this tomol.

Poking around a little more on the ground level, I saw the snout of another tomol poking out from under the supports of the Watershed Resources building, its length pushed under the building above for protection. The inlaid design of abalone shell on her bow identified this tomol as the Elye’wun, “Swordfish.”

The Elye’wun (the apostrophe in Chumash words represents a glottal stop sound, as in “uh-oh!” in English) was built in 1997 by the Chumash Maritime Assoiciation, and was the first tomol to be owned by the Chumash community itself in over 100 years. In September, 2001, the Elye’wun was paddled from Ventura Harbor to Scorpion Anchorage on the eastern end of Santa Cruz Island—the site of the old Chumash village of swaxil (note that Chumash place names are deliberately not capitalized, as such names are in English). The 21-mile voyage took 10 hours. Since then this celebratory and ceremonial crossing has been repeated almost every year. The National Park Service’s Channel Islands National Park and NOAA’s Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, the two main federal managers of the Channel Islands Biosphere Reserve, were very supportive of the first tomol crossing to the islands, and have supported others since then.

The Chumash Maritime Association, a non-profit organization with a mission of “strengthening the dignity and identity of Chumash people of all ages by reclaiming our maritime culture through practical knowledge of our homeland in all its elements,” continues to focus on building, maintaining, crewing, and voyaging with traditional tomols.

I wish I could have seen Elye’wun’s sleek length lying back there in the darkness, but I could imagine it, and it gave me goosebumps. Elye’wun embodies the adaptiveness and resilience of human cultures in the Channel Islands ecoregion, potentially reaching back to the time of the first human encounters with North America at the end of the last Ice Age.

_______

Six distinct dialects, some so different as to perhaps qualify as separate languages, were identified at about the time Spanish Catholic missions were established in the California Bight. Several Chumash languages were well documented in unpublished field notes and wax-cylinder recordings by John P. Harrington. The missions themselves may have acted as hubs for consolidation of those dialects, as people were moved to the missions or abandoned traditional villages to move there (the five missions founded among the Chumash, from south to north, are San Buenaventura, Santa Barbara, Santa Ynez, La Purisima, and San Luis Obispo). I imagine these linguistic distinctions as something like differences between Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian, which have both strong similarities and some level of mutual intelligibility. Perhaps this local linguistic divergence is similar to that among the Pueblos of northern New Mexico where I grew up. Within a 40-mile radius, nine different Pueblos speak dialects of the Tewa, Tiwa, and Towa languages.

The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians is the only federally recognized Chumash tribe, but according to my several Chumash contacts there are thirteen or fourteen “sort-of-organized bands.” They said that these were not some sort of ”ancient traditional thing,” but that Chumash society was more like a mosaic of interacting communities than some super-organized political system, with the diversity of Chumash dialects and languages reflecting that.

Chumash languages are generally placed in a language family that was called Hokan by the first generation of Franz Boas’s students of linguistics and ethnography, Alfred Kroeber and Edward Sapir. “It is a ‘language isolate,’ a technical term meaning that the Chumashan family has no known or well-established close relatives among other languages; in California, it is a true language isolate as it is not related to any other language or language family in the state,” according to anthropologist Dr. Terry L. Jones (quoted in Wiener, 2013). This explanation reminds me of some of the pockets of “language isolates” in Africa, where here and there are small groups of people speaking ancient languages where “click” sounds were common. They are often associated with “relict” hunter-gatherer cultures like the rainforest pygmies of the Congo Basin, the Hadza of northern Tanzania, and the San of the Kalahari. The click-languages were apparently washed over by the Bantu languages of the agricultural cultures that spread east from West Africa, and then south and west until their agriculture collided with the Kalahari in southwestern Africa. Could the Chumashan and other Hokan languages be a parallel to the click-languages of Africa? Perhaps they carry forward the language of the maritime peoples who arrived on the Channel Islands during the last Ice Age.

The last native Chumash speaker was Mary Ye, who spoke Barbareño; she died in 1965. It is quite remarkable that these languages survived for so long among native speakers after Spanish missionization , and that thanks especially to Harrington they were documented well enough that Chumash linguists, and language revitalization activists and programs, are working to bring the Chumash languages back to life, albeit without the cultural milieu in which they functioned.

Given the malleability and evolution of languages, and the fact that there are currently no Chumash native speakers, it is probably not possible to know exactly how words flowed over and gave meaning to this place. But humans have been speaking, story-telling, and singing across the land- and seascapes of the Chumash Channel for a very long time.

_______

The surprisingly early date of evidence for human occupation of the Channel Islands (13,000 years ago or more) has led to a tidal wave of interest how the first people got to the Americas. For many decades the paradigm among paleoanthropologists was that people first came across the Bering land bridge that connected Asia and North America when sea levels were much lower, travelled south through an ice-free corridor between continental ice sheets, and spread out. A characteristic type of spear point first unearthed near Clovis, New Mexico, gave the name to this culture. But the date of human evidence on the Channel Islands challenges this “Clovis First” hypothesis. A large extended academic family of paleoarcheologists and anthropologists is now finding evidence for another possibility: human colonization of the Pacific Coast by maritime cultures with seagoing watercraft along what has been called the “kelp highway,” after the ubiquitous coastal kelp forests that span the northern Pacific from Hokkaido to Baja California. A recent popular article in The Atlantic by Ross Anderson, titled “The Search for America’s Atlantis,” tried to summarize some of the current excitement and research. Check the “Sources and other links” section below for a few of the salient research papers, or google the names of some of the key researchers: Jon Erlandson, Todd Braje, Kristina Gill, Torben Rick, Amy Gusick, Brian Holguin, or Kristin Hoppa.

More than 2,800 archeological sites are found on the five islands that make up Channel Islands National Park, according to Dr. Kristin Hoppa, the park’s archeologist. This is a very high density of archeological sites, reaching back a very long time, and archeology here has the potential to rewrite our theories of how humans first reached the Americas. Archeological sites on the Channel Islands generally have excellent stratification—layering that provides a sequential time record—because burrowing mammals like gophers that mess it up are not found on the islands, not to mention the general lack of development, which has bulldozed, dug up, and built over many archeological sites on the California mainland (Hoppa and Vestuto, 2020). “The offshore islands of California are particularly important because they contain the longest and best-preserved archaeological sequences available for study along the west coast of North America” (Kennett, 2005, p. 5). Very few of the thousands of archeological sites on the Channel Islands have been investigated using modern scientific methods, and the biggest challenge is that probably the most informative sites are now underwater. Remember that when humans first settled on the islands during the last phase of the Ice Age (see my previous story posted here), the four northern Channel Islands of today were one large island because sea level was much lower. Coastal villages of 10,000 years ago are now underwater somewhere around the coasts of the modern islands. Underwater archeology of the sort needed to find and excavate such sites is in its infancy—although some attempts are beginning.

_______

The long archeological record on the islands is a unique and valuable resource for understanding the human-nature relationship in this place. So, for example? The middens of the Channel Islands allow ecologically inclined archeologists to examine how humans have exploited and lived from the natural ecosystems here over many millennia. One value of understanding that is to compare them with us. We are clearly not in balance with the resources of the ecosystems we inhabit—were they?

There has been a fashionable trend to view pre-Columbian indigenous cultures as ecologically sensitive and in “harmony” with their natural environments. Is that romantic view true? On the Channel Islands there is evidence that can inform that discussion… but it is complicated. And the complexity underscores another lesson from biosphere reserves that I’ve discussed before: more scientific research is always needed. Despite all we know, we don’t know enough. The scientific value of the unique island species of “California’s Galapagos” is one thing; but the value of the archeological sites on these islands in helping us understand better the cultural evolution and adaptation of humans here is another unique dimension that must be recognized and conserved.

I mentioned at the beginning of this story that “trade” of resources across the Channel Islands ecoregion may have enabled the population growth and sociopolitical complexity—and also perhaps the ecological resilience—of Chumash peoples. But “trade” is an ecologically fraught proposition. There are very few examples (although there are a few) of species other than humans that move “resources” of either nutrients (i.e. food) or energy over even very small geographical distances, much less from one ecosystem or ecoregion to another. But now our globalized economic system is dependent on just such ecologically unprecedented flows of materials and energy. Can that be sustainable?

Tomol routes, both ancient and modern, slice at right angles across the container-ship superhighway that now passes through the Chumash Channel—as if symbolically challenging the very idea of such globalized trade. Digital cryptocurrencies threaten to become the new global shell-bead money, much of it produced by “miners” with electricity-gobbling banks of computers. Neither of these modern trends seem likely to be ecologically sustainable or resilient.

Perhaps the Chumash Channel Islands Biosphere Reserve can help shed light on these critical questions about the human-nature relationship, before it is too late.

For related stories see:

- The Art of Ecological Restoration on Santa Cruz Island, January 2022.

- Evolutionary Ecology on California’s Galapagos, January 2022.

- More Ecological Explorations at the Edge of the Continent, December 2021.

- Breaking the Curse of Voodoo Economics and Designing an Ecological Economy, May 2015.

Sources and other links

- Tomol (Wikipedia)

- Gamble, Lynn H. (2008). The Chumash World at European Contact: Power, Trade, and Feasting among Complex Hunter-Gatherers. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, USA.

- Hoppa, Kristin, and Matthew Vestuto. 2020. “Navigating Cultural Landscapes through Ethnographic Place Names.” Western National Parks Association (video presentation)

- “Sewn Plank Canoes from Southern California.” Stanford Inn: Catch A Canoe. Mendocino, CA.

- National Park Service. 2018. “Fernando Librado (Kitsepawit)”

- Fernando Librado (Islapedia biography)

- Johnson, John R. 1982. “The Trail to Fernando.” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 4 (1): 132-138.

- John Peabody Harrington (Wikipedia)

- King, Charles. 2019. Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century. Doubleday, New York, NY, USA.

- Applegate, Richard B. 1974. “Chumash Placenames.” Journal of California Anthropology, 1 (2): 187-205.

- Golding, Daniel. 2020. Chasing Voices: The Story of John Peabody Harrington (video). Hokan Media LLC.

- Blackburn, Thomas C. 1975. December’s Child: A Book of Chumash Oral Narratives. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, USA.

- Chumash Maritime Association

- NPS, 2016. ”Chumash Tomol Crossing.”

- Pagaling, Eva (2018) “Dark Water Journey.” NOAA, Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary.

- Santa Barbara Maritime Museum. 2014. “Revitalization of the Chumash Tomol.”

- Chumashan languages (Wikipedia)

- Wiener, James Blake (26 March 2013). “Polynesians in California: Evidence for an Ancient Exchange?”. Ancient History.

- Chumash language and its revitalization, video interview with Matthew Vestuto. Santa Barbara Historical Museum. 2017.

- Kanyon Sings a Chumash Grandmother’s Song

- Anderson, Ross. 2021. “The Search for America’s Atlantis.” The Atlantic, Sept. 7, 2021.

- Erlandson, Jon M., and Todd J. Braje. 2011. “From Asia to the Americas by boat? Paleogeography, paleoecology, and stemmed points of the northwest Pacific.” Quaternary International, 239: 28-37.

- Gill, Kristina M., and Kristin M. Hoppa. 2016. “Evidence for an Island Chumash Geophyte‑Based Subsistence Economy on the Northern Channel Islands.” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 36: 51–71.

- Gusick, Amy E., and Jon M. Erlandson. 2019. “Paleocoastal Landscapes, Marginality, and Early Human Settlement of the California Islands.” In: In book: An Archaeology of Abundance: Reevaluating the Marginality of California’s Islands (pp.59-97). University Press Florida.

- Kennett, Douglas J. (2005). The Island Chumash: Behavioral Ecology of a Maritime Society. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, USA.

- Rick, Torben C., et al. (2014). “Ecological Change on California’s Channel Islands from the Pleistocene to the Anthropocene.” BioScience, 64 (8): 680–692.

February 3, 2022 3:45 pm

Hi Bruce, excellent read and very fascinating boats! I had heard of these but appreciate the added details I know now from your descriptions here. But I’d like to add just one quick note about the potential for tule boats ever being used for channel crossing, specifically concerning their “fragility and water-logging propensity”. I was involved in an experiment last winter (Jan 2021) in seeing if a tule boat could have ever been used on the upper Colorado River, especially for travel in the Grand Canyon. They were very common boats on the Lower Colorado – just as in the SF Bay and CA coast – with some very intriguing hints they might have made it farther north as well. My friend Tom Martin has been working on CO River boat history for some time now and has wondered exactly that question you pose above, if a tule boat would have been robust enough to have ever allowed travel down the Canyon. So we tried it out: Tom built a crude tule boat and I rowed it down the River on a 30-day private rafting trip. Google “tule boat Grand Canyon” for the full story but in brief the tule boat was floating just as high and easy to row by the end of the trip as the day it was launched – 277 miles, dozens of rapids, 30 days total. So I would suggest that it would have been no problem to reach the Channel Islands on a tule boat… perhaps make a nice experiment for someone!

February 7, 2022 3:23 pm

Hi Peter, Glad you enjoyed the story, thanks for the feedback! And wow, amazing new information about the potential toughness of tule boats! I was simply repeating the opinions of others about their potential fragility and waterlogging tendencies… But your report about Tom Martin’s tule boat going down the Grand Canyon seems to prove otherwise. I know you have worked in and around Point Reyes, and certainly the Miwok would have been crossing Tomales and San Francisco Bays on tule boats — I have never heard reports of them on the open Pacific side of Point Reyes, though, for example from Drake’s expedition. Have you? That said, you are right that someone should do some more experimenting with this. I know there are some Native American groups around San Francisco Bay who are starting to reconstruct tule boats… Maybe they should do a collaboration with the Chumash tomol builders. Thanks for that fascinating reply to my post!