November 10th, 2012. Hurricane Sandy had brushed by North Carolina’s Outer Banks on Halloween, and some beachfront neighborhoods were still assessing the damage and digging out a week and a half later.

But today was a glorious fall Saturday, with a deep blue sky and perfect Goldilocks temperatures: not too hot, not too cold. Most people don’t think of the Outer Banks as a biodiversity “hotspot,” but some rare and unusual creatures are found here, and our goal was to experience this unique biodiversity “up close and personal.”

We parked at the trailhead of a network of trails at The Nature Conservancy’s Nags Head Woods Preserve, and set off. Nags Head Woods is situated in the middle of the northernmost, most developed, and most familiar, part of the Outer Banks. It backs against Albemarle Sound to the west, at a relatively wide part of the long and skinny barrier island. The woods cover old, now-stabilized dunes, and the topography of the old dunes creates dozens of depressions of varying sizes that collect water, forming ponds among the pine, oak, hickory, holly, and sweet gum. All the ponds were full after at least six inches of recent rain from Hurricane Sandy.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) has worked with the local communities of Nags Head and Kill Devil Hills since 1977 to protect Nags Head Woods. About 1,400 acres of maritime forest and interdunal ponds are now part of preserve. More than 300 species of plants are found here, including several species that are rare in North Carolina, such as wooly beach heather (Hudsonia tomentosa), water violet (Hottonia inflata), mosquito fern (Azolla caroliniana), and a tiny orchid called the southern twayblade (Listera australis). Great names, don’t you think?

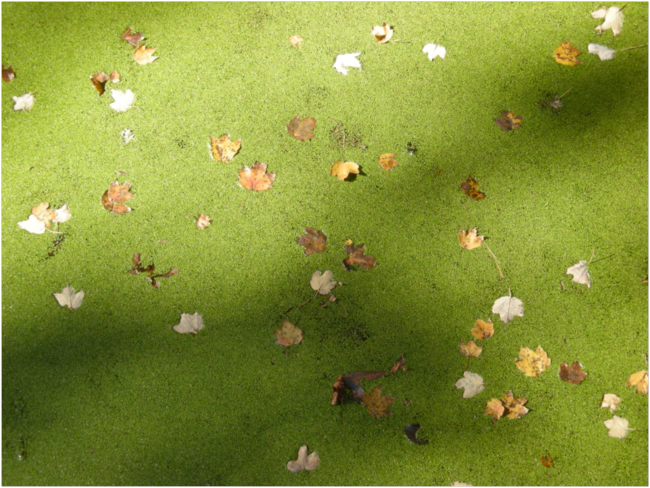

The trail led to a pond that was completely green, its surface totally covered with duckweed, a tiny floating aquatic plant in the genus Lemna, and I had a “flashback.” When I see the green of Lemna on a pond it always makes me think of what now seems like the long-forgotten era of concern about human population growth, resource use, limits to growth, and sustainable development – hot topics in the 1970s, 1980s, and into the 1990s, and now hardly mentioned or thought about, it seems.

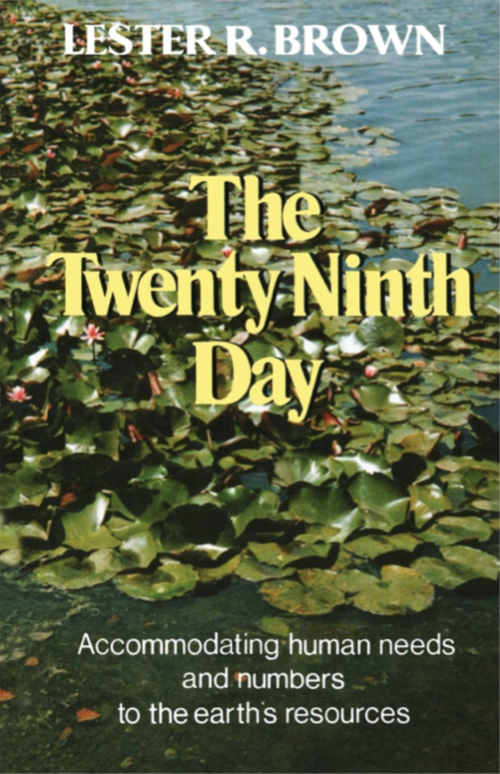

In 1972, Donella and Dennis Meadows, in their book Limits to Growth, used the following story to illustrate the dangers of the exponential growth of population and use of natural resources that was occurring then – as it is still, now, today: “A French riddle for children illustrates another aspect of exponential growth–the apparent suddenness with which an exponentially growing quantity approaches a fixed limit. Suppose you own a pond on which a water lily in growing. The lily plant doubles in size each day. If the plant were allowed to grow unchecked, it would completely cover the pond in 30 days, choking off the other forms of life in the water. For a long time the lily plant seems small, so you decide not to worry about it until it covers half the pond. On what day will that be? On the twenty-ninth day. You have just one day to act to save your pond.” In 1978 Lester Brown, founder of Worldwatch Institute, used the “punch line” of this story for the title of his book, The Twenty Ninth Day.

In the late 1990s I was writing some curriculum materials about global human ecology and sustainable development for the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS), a developer of cutting-edge high school textbooks in biology and ecology. My material was eventually included in “The Commons: An Environmental Dilemma,” released in 2001, and still available in a 2006 edition. I was searching for a dramatic way to illustrate exponential growth – an experiment or demonstration in which students in high school classrooms could observe the “Twenty Ninth Day” phenomenon. They couldn’t plant water lilies in a pond and observe them, but I thought they might be able to replicate similar exponential growth in their classrooms with duckweed. I collected some Lemna from a pond near my house, and a few jugs of nutrient-rich pond water, and tried to grow them in cups and bowls on the sunny countertop of my cramped, but sunny, kitchen. The “experiment” competed for space with cooking and dishwashing for more than a month.

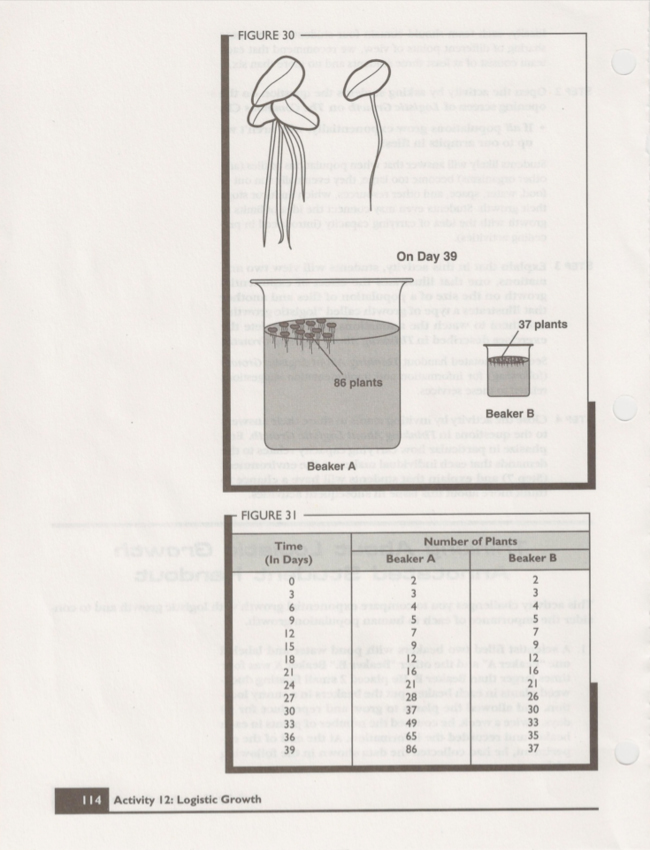

I made careful observations and – a big surprise to me – the experiment worked. I translated the volumes of my bowls and cups to the metric measurements universally used by scientists. Here is how it was finally described in the text of “The Commons: An Environmental Dilemma”: “A scientist filled two beakers with pond water and labeled one “Beaker A” and the other “Beaker B.” Beaker A was four times larger than Beaker B. He placed 2 small floating duckweed plants in each beaker, and put the beakers in a sunny location, and allowed the plants to grow and reproduce for 39 days. Twice a week, he counted the number of plants in each beaker and recorded the information. At the end of the experiment, he had collected the data shown in the following table.”

My kitchen-counter duckweed experiment makes the big time in “The Commons: An Environmental Dilemma” (BSCS, 2001)

The activity guide for teachers suggested that they have their students plot the data from the two beakers on a graph, and discuss the results. When plotted, the data from Beaker A essentially show a classic “J-shaped” curve of exponential growth, with a doubling time of about seven days. Beaker B’s population growth curve shows the classic flattening out of the exponential “J-curve” into the “S-shaped” curve of logistic growth, beloved of population ecologists, as the “limits to growth” and “carrying capacity” in this much smaller beaker are reached. Honestly, I was amazed that duckweed was so cooperative, and the kitchen-counter experiment demonstration worked so well.

That memory was the source of my “flashback” when I saw the completely green, Lemna-covered pond at Nags Head Woods: it was a Thirtieth-Day Pond. Walking and passing ponds with varying coverage of Lemna, from zero to 100%, old questions came back. The Nags Head ponds got me pondering again the future of humans on Spaceship Earth. “Spaceship Earth” is another old image and phrase, this one reaching back even earlier, to a 1965 speech by Adlai Stevenson II, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, in which he said “We travel together, passengers on a little spaceship, dependent upon its vulnerable reserves of air and soil, all committed for our safety to its security and peace; preserved from annihilation only by the care, the work, and, I will say, the love we give our fragile craft. We cannot maintain it half fortunate, half miserable, half confident, half despairing, half slave to the ancient enemies of man, half free in a liberation of resources undreamed of until this day. No craft, no crew can travel safely with such vast contradictions. On their resolution depends the survival of us all.”

Why, I wondered, are some ponds completely covered with green Lemna, while others have no Lemna at all? Those Lemna-less ponds have water stained almost black with tannins from decaying leaves and other organic material, and their still, black surfaces made them into perfect, beautiful mirrors of the surrounding woods and sky on this glorious fall day. Why are some ponds one-fourth covered in green, some one-half, and some three-quarters? Could it be their size? Depth? Amount of shade? None of these explanations seemed obvious. Maybe a passing duck landed on one, carrying a few Lemna on its feet to colonize it, but not its neighbor pond? Maybe a deer died in the mini-watershed of one pond, fertilizing it with nitrogen from its decaying body, and launching an exponential explosion of Lemna, while the neighbor pond struggled with lack of nutrients and stayed black, dominated by acidic leaf tannins? Was a black pond once a green pond? Or vice versa? Maybe… maybe… It’s easy to imagine a long list of “maybes” that might explain the diversity of Nags Head Woods ponds. Trying to figure out these patterns and explain them would be a challenge for multiple Ph.D. dissertations. At least here, TNC has preserved a natural laboratory for such research, should some student want to undertake it. Such places are rare, very rare, and therefore their scientific value is immense. On the resolution of these ecological questions may depend the survival of us all.

In a 2003 paper titled “Catastrophic Regime Shifts in Ecosystems: Linking Theory to Observation,” ecologists Martin Scheffer and Stephen Carpenter conclude that “Occasionally, surprisingly large shifts occur in ecosystems. Theory suggests that such shifts can be attributed to alternative stable states. Verifying this diagnosis is important because it implies a radically different view on management options, and on the potential effects of global change on such ecosystems. For instance, it implies that gradual changes in temperature or other factors might have little effect until a threshold is reached at which a large shift occurs that might be difficult to reverse.” Worrisome words for worry warts on Spaceship Earth. We humans seem to be pushing our planet toward thresholds of climate warming and extinction of species that might tip it, and us, off into the lifelessness of all of our neighbor planets – that is, of all the planets we know about.

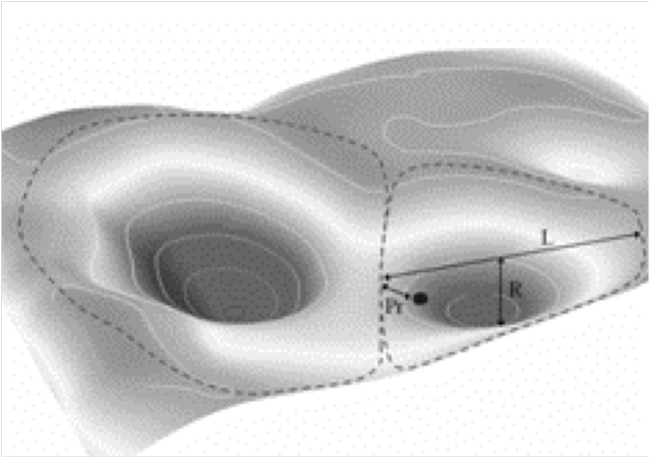

In a 2004 paper titled “Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social–Ecological Systems,” ecologists Brian Walker, C. S. Holling, Stephen Carpenter, and Ann Kinzig discuss the challenges of protecting Spaceship Earth in language that is the modern equivalent of the discussions of four decades ago: “Resilience (the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks) has four components—latitude, resistance, precariousness, and panarchy—most readily portrayed using the metaphor of a stability landscape.”

The caption of this figure in their article reads: “Fig. 1a. Three-dimensional stability landscape with two basins of attraction showing, in one basin, the current position of the system and three aspects of resilience, L = latitude, R = resistance, Pr = precariousness.” This somewhat surreal figure made me think of a fine-scale topographic map of Nags Head Woods, with the depressions between the ancient dunes filled now with ponds. Green ponds, black ponds, in-between ponds…

Stability landscape? Where is the system now?

But we are back, after hiking full circle. Back to the car, by the green pond, the Thirtieth-Day Pond, completely covered by Lemna, next to the parking lot.

Looking at the preserve sign again, something new jumped out, the quotation from Henry David Thoreau, at the top right, from his essay “Walking,” published 150 years ago, in 1862: “In wildness is the preservation of the world.” Thoreau is best known for “Walden,” which described how a pond in Massachusetts was a metaphor for living a fulfilled human life.

This time I got it, Thoreau’s radical insight. Right here on the Outer Banks, a bit of nature left in its natural state, a few handfuls of ponds, are a laboratory, and a lesson, that may hold the key to whether our human species can invent a sustainable and resilient way of living on Spaceship Earth. Green pond? Black pond? How many days do we have left to act to save our pond? We will try our best; we’ll wait and see.

For more photos, visit the Picasa gallery.

Related Links:

- TNC Nags Head Woods Preserve

- The Commons: An Environmental Dilemma, Biological Sciences Curriculum Study

- Resilience Alliance

December 12, 2013 4:13 am

[…] last year’s blog about the Outer Banks, read Pondering the Ponds of Nags Head Woods and about early American naturalists John and William Bartram and John James […]

March 6, 2014 11:24 pm

I really enjoyed this blog post and will be using with my students in an upcoming Applied Systems Thinking class in which we use Donella Meadows book Dynamic Systems Thinking. Thanks for sharing.