July 2015. The word “sublime” isn’t used much these days, but it would have been 150 years ago. America’s westward expansion, and the Civil War, embedded in the context of global exploration and a rapid expansion of science, were challenging the foundations of the old worldview Americans had carried from Europe. The word sublime was then most closely associated with the New England Transcendentalist philosophers and poets, the Luminist painters of the Hudson River School, and the nature writers arguing for a spiritual value for wild nature and for its preservation. The era is bracketed by Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) and John Muir (1838–1914). It spans the overlapping lives of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), David Henry Thoreau (1817–1862), Charles Darwin (1809–1882), Alfred Russell Wallace (1823–1913), Thomas Cole (1801–1848), Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Walt Whitman (1819–1892), John Burroughs (1837–1921), and Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902).

On a recent trip to Colorado, I was thinking especially of Albert Bierstadt. After the endless flatness of the middle of the American continent, the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains rises steeply to the Continental Divide west of Denver, and it was here that Bierstadt came in 1863, seeking to capture the sublime on canvas with a trip to the high country.

Albert Bierstadt was born in Germany in 1830, but came with his parents to Massachusetts at one year old. At age 23 he returned to Germany to study painting in Dusseldorf, a school that emphasized making naturalistic, outdoor, plein air paintings – a method also advocated by Thomas Cole, founder of the Hudson River School of American art. After four years in Germany, Bierstadt returned to the U.S. and began to paint in New England and New York, including in the Hudson River Valley. In 1859 he travelled west with a government survey expedition as its artist and photographer. Infatuated with western scenery, he went west again in 1863, through Colorado and on to California, with his friend and patron, Fitz Hugh Ludlow, whose wife, Rosalie, Bierstadt would eventually marry.

In Denver, Bierstadt befriended William N. Byers, editor of the Rocky Mountain News, who soon learned of his wish to find a majestic Rocky Mountain scene for a grand painting. Byers was an accomplished outdoorsman who knew the high country west of Denver well, and he resolved to lead Bierstadt to an especially spectacular alpine view. Describing that trip 27 years later in an article in The Magazine of Western History, titled “Bierstadt’s Visit to Colorado: Sketching for the Famous Painting Storm in the Rocky Mountains,” Byers wrote, “Bierstadt …came first to Denver, in search of a subject for a great Rocky Mountain picture, and was referred to me – probably because I had at that time something of the reputation of being a mountain tramp.” Byers had an idea of where to take Bierstadt for a grand alpine view, and they set off on horseback from the mining town of Idaho Springs, up the Clear Creek valley west of Denver. “It rained; the creek was high, its many crossings through the foaming current and among the boulders exceedingly unpleasant and difficult, if not dangerous… I knew that at a certain point the trail emerged from the timber, and all the beauty, the grandeur, the sublimity, and whatever else there might be in sight at the time, of the great gorge and the rugged and ragged amphitheatre at its head, would open to view in an instant like the rolling up of a curtain.” Bierstadt, although soaked and exhausted by the day’s travel, was so taken by the scene that he insisted on unpacking his paints and making an oil sketch of the passing storm over the lake and mountains.

I’m probably, somehow, related to this William Newton Byers, who guided Bierstadt to the mountain lake on the side of Mt. Evans where he experienced, and tried to communicate in his art, the Colorado Sublime. Originally from Ohio, Byers moved with his parents to Iowa in 1851. He later worked as a surveyor in the Nebraska Territory, and was an early settler in Denver, where he eventually founded and served as editor of the Rocky Mountain News. My own great-grandfather, Perry Byers, moved with his parents from Ohio to Iowa in the late 1840s. My Iowa-farmer ancestors – Methodist, not Mormon – did not keep much track of their relatives who pushed on westward, so my family’s genealogical records don’t connect with William Newton Byers, Bierstadt’s guide. But for all I know he was a cousin of my great-grandfather.

Like many of his plein air paintings, Mountain Lake was a preliminary oil sketch. Bierstadt took it back to his studio in New York as a study for a grand painting, A Storm in the Rocky Mountains—Mount Rosalie. In contrast to that exaggerated, grandiose studio work, the naturalism of Mountain Lake is surprising and refreshing. An interesting side-note is that Bierstadt named the peak in the painting, now called Mt. Evans, after his travelling companion’s aforementioned wife, Rosalie, with whom he was apparently as infatuated as he was with the sublime scenery.

———–

Various of the people I mentioned in my opening paragraph wrote about the meaning of the “sublime.” For example, Thomas Cole, the founder of the Hudson River School, described being in a wild setting and feeling “overwhelmed with an emotion of the sublime such as I have rarely felt. It was not that the jagged precipices were lofty, that the encircling woods were of the dimmest shade, or that the waters were profoundly deep: but that over all, rocks, wood and water, brooded the spirit of repose, and the silent energy of nature stirred the soul to its inmost depths.”

The concept of the “sublime” that Cole and his contemporaries were exploring resonates with me now, and always has. Being in the high mountains – perhaps exploring off trail, perhaps with a sudden storm coming on, thunder rumbling – has always been for me a confusing blend of exhilaration and terror. The effect of being in a wild landscape far from those dominated by our agriculture and cities has always been to give me an immediate, felt sense that “nature” doesn’t give a shit about me. The big, old world that is dominant there doesn’t care whether I live, or die, or even exist. The psychological effect of being in wild nature, for me, has always been a feeling of a much expanded sense of “self,” and of the meaning and purpose of life. Being in the wilderness has always “put me in my place” – a much bigger, older abode than the hassle-filled scene of my usual life down in the “low country.” And for me a wild place, with scarce traces of my own species, has always given me a sense of a deep, interconnected, cosmic meaning, and a feeling of well-being and calm.

I can imagine – or at least I try to imagine – that for some people the feeling of being so tiny and insignificant in an uncaring Universe that is completely oblivious to our presence would be uncomfortable, scary, even terrifying. But for me, wild nature has always felt like my true home.

So it did, I think, for the people I have come to think of as my “eco-philosophical ancestors” – the people named above, and many others, who together, in 19th-Century America, evolved a new view of the relationship of humans and nature. They collectively carved this new worldview out of the dominating conventions of Euro-Christian thought. Their new, revolutionary American worldview came to see the complex natural world as somehow holy and divine, full of spirit and beauty, but with no dependence on god or gods, faith or belief, human exceptionalism or salvation, and embracing humans as a natural part of that wholeness.

My personal view is that all of these eco-philosophical ancestors were able to acknowledge that the narrow, dogmatic, religious explanations that had prevailed in Euro-Christian culture up until their day just could not stand up to simple logical scrutiny anymore, given the flood of knowledge of ecology and anthropology pouring in as the result of global exploration and economic expansion. Each of them was willing to step into new territory, the explorers of a new philosophical and scientific landscape that would lead toward a new worldview, the holistic, ecological worldview pioneered by Alexander von Humboldt.

——-

Barbara Novak, whose analysis of the Hudson River School, Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting,1825-1875, is still the definitive work on its wider cultural importance, wrote that “The new significance of nature and the development of landscape painting coincided paradoxically with the relentless destruction of the wilderness in the early nineteenth century. The ravages of man on nature were a repeated concern in artists’ writing, and the symbol of this attack was usually “the axe,” cutting into nature’s pristine – and thus godly – state. In his “Essay on American Scenery” (1835), an essay that articulates the spirit that was to dominate much American landscape painting for thirty years, Thomas Cole found America’s wilderness its most distinctive feature,

‘because in civilized Europe the primitive features of scenery have long since been destroyed or modified … And to this cultivated state our western world is fast approaching; but nature is still predominant, and there are those who regret that with the improvements of cultivation the sublimity of the wilderness should pass away; for those scenes of solitude from which the hand of nature has never been lifted, affect the mind with a more deep toned emotion than aught which the hand of man has touched. Amid them the consequent associations are of God the creator – they are his undefiled works, and the mind is cast into the contemplation of eternal things.’”

The American view that wild nature, untamed and unspoiled, has an aesthetic and spiritual value – its “sublime” value – also owes an acknowledgement to an important photographic pioneer of the period, William Henry Jackson (1843-1942). Jackson was born only five years after John Muir. He was the photographer on the U.S. government surveys of the Yellowstone River and Rocky Mountains led by Ferdinand Hayden in 1870 and 1871. Thomas Moran, another painter associated with the Hudson River School, was also part of the 1871 expedition, and Jackson and Moran worked closely together to visually document the Yellowstone region. Their photographs and paintings played an important role in convincing Congress in 1872 to establish Yellowstone National Park, the first national park in the U.S., and the world.

Jackson, perhaps through his friend Moran, knew of Bierstadt’s paintings Mountain Lake and A Storm in the Rocky Mountains. In what may be the earliest known attempt at “rephotography” – going to a place with a previous visual image and repeating the image from the same location, thereby enabling a “time-lapse” comparison of the environmental change that has occurred there – Jackson made a deliberate photograph of the scene of Bierstadt’s Mountain Lake painting from nearly the same viewpoint ten years later, in 1873.

Moran and Jackson were instrumental in providing visual images of American wilderness – transcendental, luminous, sublime landscapes “untrammeled by man.”

Thoreau, their contemporary, wrote in his essay “Walking,” published posthumously in The Atlantic Monthly in 1862: “I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil – to regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society”. Here Thoreau is presenting the Transcendentalist case for wild nature as the locus of the sublime. His famous phrase “in wildness is the preservation of the world” comes from that essay.

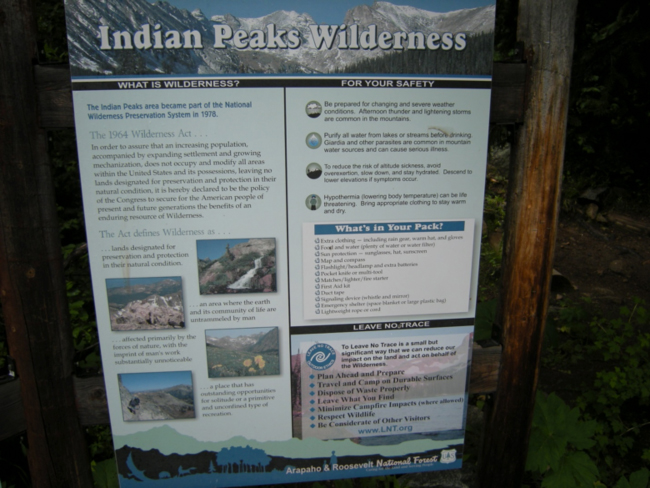

The views of Thoreau, Cole, Bierstadt, Moran, Jackson, Muir, and many others eventually led to the Wilderness Act of 1964, which explained its purpose in words that echoed them approximately a century later: “In order to assure that an increasing population, accompanied by expanding settlement and growing mechanization, does not occupy and modify all areas within the United States and its possessions, leaving no lands designated for preservation and protection in their natural condition, it is hereby declared to be the policy of the Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness. … A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

———

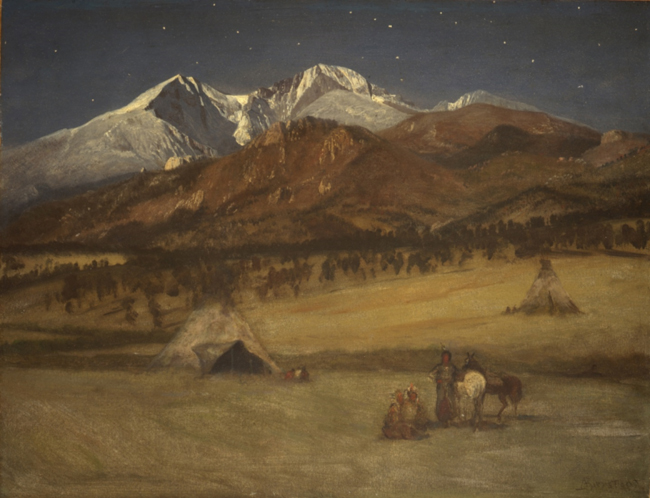

Please permit me one final leap and link to a related topic – the psychologically-agonized relationship between the painters of the Euro-American sublime and Native Americans. Cole, Bierstadt, and other Hudson River School painters incorporated Native Americans into their paintings of otherwise “wild” and “wilderness” nature. Perhaps they were reflecting the astonishment and fascination of their era with indigenous American cultures and worldviews that were embedded in nature and its holiness and innocence, rather than at war with it, as was their own Euro-Christian culture and worldview. This culturally-conflicted view is perfectly illustrated by Bierstadt’s painting, Indian Encampment, made sometime in 1876 or 1877. That painting, more natural and observational than his exaggerated studio paintings, resulted from his two-week sketching trip to Estes Park, Colorado, between December 23, 1876 and January 9, 1877. By painting a night scene, Bierstadt emphasized the effects of snow on the distinctive shape of Long’s Peak, now in Rocky Mountain National Park, with almost photographic clarity. But his Native Americans have a ghostly quality, blurry and unfocused compared to the sharp, sublime snow of the high peaks above them. No wonder: this painting was made 13 years after the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864, and the relocation in 1868 of the Arapahoe and Cheyenne to reservations in Oklahoma, way out in the flat belly of the continent, and far, far from their true, sublime Rocky Mountain home.

The wilderness area in the high country above and west of Boulder, Colorado, an old haunt of mine, is now named the Indian Peaks Wilderness. It encompasses a section of Front Range peaks named after tribes and chiefs of the Native Americans whose territory and home this was before Europeans took it from them. Thankfully, it is still a place where we can all experience the sublime, and imagine our connection with our ancestors, indigenous and immigrant, who experienced it there.

For related stories see:

- Visiting Revolutionary Ecological Relatives in Philadelphia

- Not Man Apart: Genealogy of an Ecological Worldview

- At Church with John Muir

- The Art of Ecology: A Pilgrimage to the Heart of the Andes

- The Art of Ecology: Sketching with Cole and Church

Sources and Related Links:

- Bierstadt’s Visit to Colorado: Sketching for the Famous Painting, “Storm in the Rocky Mountains.” By William Newton Byers. Magazine of Western History, Vol. XI, No. 3, January 1890.

- Get to Know: Albert Bierstadt’s Mountain Lake. Nicole A. Parks. 2013. Denver Art Museum.

- William Newton Byers

- A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mt. Rosalie. Albert Bierstadt. 1866. Brooklyn Museum.

- Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting, 1825-1875, With a New Preface. 2007. Barbara Novak.

- William Henry Jackson

- Mountain Lake photograph by William H. Jackson

- 1862 essay by David Henry Thoreau, published in The Atlantic Monthly

- The Wilderness Act of 1964

- Indian Encampment, painting by Albert Bierstadt, circa 1876-1877.

September 10, 2015 10:42 am

Hi Bruce,

My son in law Anton Seimon forwarded your link to me. I thoroughly enjoyed reading your article “In search of the sublime with Albert Bierstadt”. I have a great interest in Albert Bierstadt and William Jasckson. I had a book of Thomas Felder’s photography, copying William Jackson photos in as close proximity as possible. I am a watercolor artist and Albert Bierstadt is one of my favorite artists, I have seen and enjoyed much of his work. I have also hiked the Indian Peaks Wilderness and have painted some of the beautiful scenery there. I am now living in Australia and do miss Colorado very much. My watercolor website is quite old but you can see how I have been inspired by my hikes. My new website will be much more refined along with my paintings and should be up in about four months. Your article has made me want to get back there even more and hopefully next summer I will get there.

Regards,

Michael Piegdon

September 14, 2015 6:48 pm

Greetings Michael,

What a pleasant surprise to get your message from Australia, making so many connections across the continents! Thanks to Anton for helping to remind me that the world seems sometimes a small place.

On your watercolor website I can see the echoes of Bierstadt and his luminism in some of the Colorado paintings. I’m linking them here so other readers can find them also:

Colorado: http://www.michaelpiegdonwatercolorist.com/gallery/displayimage.php?album=3&pos=9

Indian Peaks: http://www.michaelpiegdonwatercolorist.com/gallery/displayimage.php?album=3&pos=20

Rocky Mountain High: http://www.michaelpiegdonwatercolorist.com/gallery/displayimage.php?album=3&pos=32

And thank you for making me aware of John Fielder’s wonderful rephotography of Jackson’s Colorado scenes! Interested readers might want to know about Fielder’s two volumes: Colorado 1870-2000: Historic Landscape Photography by William Henry Jackson and contemporary rephotography by John Fielder. 1999. Westcliffe Publishers. Volume I (1999) has 156 comparison photo pairs, and Volume II (2005) has 110 additional photo pairs! The description of the book states that Jackson photographed “a Colorado landscape both pristine and already dramatically affected by the onslaught on western civilization. Standing exactly where Jackson stood, and pointing his own camera in precisely the same direction, John Fielder has rephotographed Jackson’s Colorado images to capture the often startling change that has occurred over the last century. The result is both breathtaking and stark, hopeful and disquieting. John Fielder describes the profound experience of traveling the state and seeing the landscape from Jackson’s perspective, and reflects upon changes of the last 130 years.” http://www.amazon.com/Colorado-1870-2000-John-Fielder/dp/0983276943

Maybe next summer we can meet in the Colorado high country and do some more searching for the sublime in Bierstadt’s and Jackson’s footsteps.

Bruce