September 2014. Sipping a draft Mützig in the patio restaurant at the hotel in Gisenyi, lightning flashing out over Lake Kivu. Storms still around, after the fierce downpour this afternoon driving from Musanze to Gisenyi, where we stopped along the Sebeya River to see the raging torrent of liquid mud, as if the rain had punctured an artery of the land, and now it was gushing its red-brown blood. Mützig is a bright, honey-colored lager with enough hoppiness for my taste, one of the popular Rwandan beers made at the Brailirwa Brewery here in Gisenyi, now part of the giant global Heineken brewing family. It’s made from that muddy water from the Sebeya.

Mützig? A word with an umlaut doesn’t exactly sound like a Kinyarwanda word. Kinyarwanda is the language of Rwanda, in the Bantu family of African languages. Umlauts are German, and this beer bespeaks part of the history this complex country.

For centuries the Kingdom of Rwanda, protected by its geography and mountainous topography, was cut off from dramatic changes happening elsewhere in Africa. The isolationist kingdom, ruled by the Mwami, or king, repelled other African tribes and colonial powers alike until the late 19th Century. The famous American explorer of Africa, Henry Morton Stanley, tried to penetrate Rwanda in 1874, but was chased back by arrows near Lake Ihema in what is now Akagera National Park in the eastern part of the country. At the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, Germany was trying to catch up in the colonial “scramble for Africa,” and was given control over Rwanda, although no European had set foot in the country at that time. The first to do so was Count Gustaf Adolf von Götzen in 1894, who entered Rwanda at Rusumo Falls in the southeast and crossed to Lake Kivu in the west, meeting the Mwami during his trek.

Rwanda was formally absorbed into German East Africa in 1898. The Germans were impressed with the organized administrative structure of the isolated kingdom – almost feudal – and promptly co-opted it for their own colonial purposes. But before much could change, World War I intervened, and with Germany’s defeat, Belgium – the colonial ruler of Rwanda’s giant neighbor, the Belgian Congo – took over in 1919 under a League of Nations mandate. Belgium ruled Rwanda until a rushed independence in 1962 pushed the country back into its historical complexities and contradictions. Those fermented until a sputtering civil war began around 1990, lighting a long fuse that finally exploded in the horrific genocide of 1994. After belated intervention by the French and the United Nations, the military victory of the Rwandan Patriotic Front, and finally an end to the violence, a tide of refugees returned from neighboring countries, hungry for land.

That’s where part of this story starts. Where does the Sebeya River start? Where is its watershed, and why is it bleeding so badly? It reaches east and southeast from Gisenyi into mountainous uplands of the Albertine Rift, that western branch of Africa’s Great Rift Valley, into what was once the Gishwati Forest.

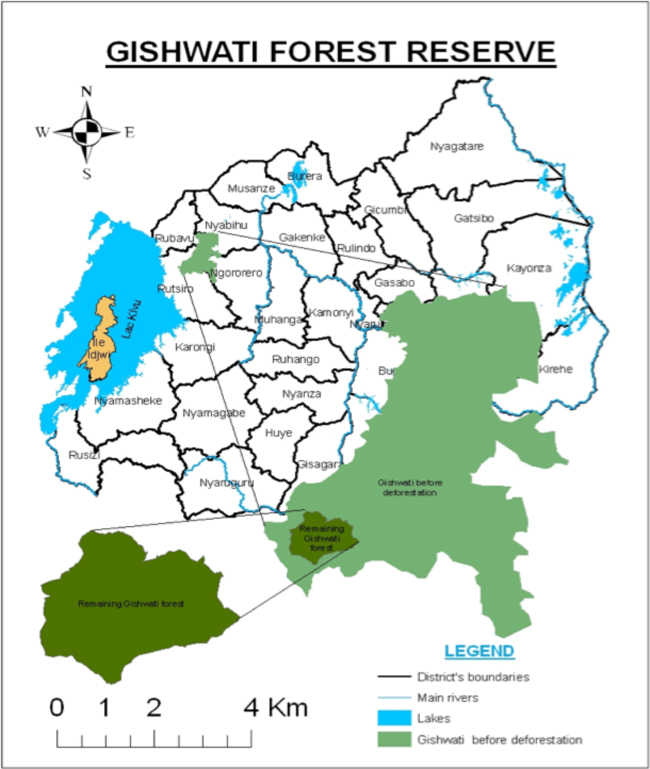

Gishwati was, until about thirty years ago, the second-largest area of Afromontane forest in Rwanda. In the 1970s, in the Belgian Protectorate of Rwanda, it was a protected forest reserve of 28,000 hectares. In 2002, less than a decade after the flood of land-hungry refugees returning from neighboring Zaire after the civil war and genocide settled here, the forest area had been reduced to an estimated 600 hectares, only 2% of its former area. Former forest had become fields of beans, potatoes, and maize covering the steep hills and ridges. No wonder the land is bleeding.

In 2005, with funding from a US-based NGO called the Great Ape Trust, a process of forest restoration began. An initial expansion of 286 hectares was completed in 2007, and more protected land was added in 2008 and 2009, bringing Gishwati Forest Reserve up to its current size of 1,484 hectares.

After spending the night in Gisenyi we drove up into the Sebeya watershed, heading for what was left of Gishwati Forest. We arrived at the office of the Forest of Hope Association, a small house in a tiny ridge-top settlement, and were greeted by its young and enthusiastic director, Thierry Aimable Inzirayineza, just before the storm hit. Soon the rain was pounding the tin roof and we were shouting to be heard. Lightning was striking so close I hoped this building had a lightning rod. Finally the storm passed and we drove up slippery roads to a small village. We got out to walk up to the top of the highest ridge in the area, a viewpoint over the forest.

The sun was breaking through post-storm clouds now in the late afternoon. A rowdy troop of local kids followed along with us, attracted by the unexpected arrival of their friend Thierry and a group of outsiders in a big silver Land Cruiser. At the top of the ridge the view of the forest and the surrounding landscape was glorious. The sharp volcanic cones of Karisimbi and Mikeno in the Virunga Mountains loomed through misty skies to the north.

View to the north over Gishwati Forest, Mount Mikeno in DRC left, Karisimbi on the Rwanda-DRC border right

We looked down on Gishwati Forest. Imagine! A community of chimpanzees, our closest evolutionary relatives, live down there in that small fragment of forest! They must be wet after the rain, probably finishing the day’s feeding and starting to make nests for the night.

A study of Gishwati chimpanzees by American primatologist Rebecca Chancellor and her colleagues estimated that there are between 19 and 29 individuals in this small group, based on DNA analysis from fecal samples. Their research found that genetic diversity in Gishwati chimps is currently similar to that in other chimpanzee communities, suggesting that this population has only been isolated for a short time. However, genetic diversity is expected to decrease over time in such a small, isolated population, threatening its long-term survival. Continued inbreeding and genetic drift could eventually reduce the population’s ability to adapt to environmental change, and lead to the buildup of maladaptive traits. For that reason, the Government of Rwanda and a variety of international donors have been discussing the possibility of restoring a forest corridor that would connect what remains of Gishwati Forest, through another protected forest fragment called Mukura Forest Reserve, to Nyungwe National Park, 70 kilometers to the south. Now-isolated Gishwati chimpanzees would then be able to move through the forested corridor and interbreed with the much larger Nyungwe population.

From the high ridge we could look down on the headwaters of the Pfunda River, a major branch of the Sebeya. Earlier that morning we had driven through the Pfunda Tea Estate, its emerald terraces of tea pushing up toward the edges of the Gishwati Forest in places. Tea bushes protect soil from erosion much better than the typical annual crops that would be planted here – beans, maize, maybe potatoes. They create something of a buffer zone around the forest, deterring the dense settlement of subsistence farmers with a crop that is sipped in “civilized” cities a world away. Pfunda’s tea production methods are environmentally-certified by the Rainforest Alliance. The tea estate benefits from its proximity to Gishwati because it depends on flows of clean water from the forest for processing tea.

The Brailirwa Brewery also depends on water flowing from Gishwati in the Pfunda and Sebeya River watersheds. The water treatment plant just above Gisenyi has the unenviable challenge of getting rid of the sediment and returning the water into a drinkable – and brewable – quality. The treatment plant manager, Justin Mwikarago, described the process to us, emphasizing the cost of adding chemical flocculants to this muddy water to enable the system to filter out the sediment.

What about the future of Gishwati Forest? Since 2012, the Forest of Hope Association (FHA) has been the sole NGO working with local communities on forest conservation. In August of this year, 2014, FHA received a grant from the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund that will support the development of a five-year management plan, and establish community forest protection committees. The community committees will be trained in environmental, forest, and mining laws, and how to document and report violations of those laws. On October 15, 2014, a Cabinet meeting chaired by Rwanda’s President, Paul Kagame, approved a draft law establishing the Gishwati-Mukura National Park, and so Gishwati and its tiny sister forest Mukura may soon together form Rwanda’s fourth national park. There are some hopeful developments in the Forest of Hope. But hope, to be realized, needs action, and action requires incentives, and human and financial resources.

Mützig. It’s a quite quaffable lager, bitter hoppiness balancing the sweet malt just enough. As I sipped my Mützig this evening I imagined tasting all the complex connections in the Gishwati-Mützig ecosystem: rain falling on the mountain forest, dripping off leaves sheltering chimps, gathering in a web of microwatersheds, flowing through tea estates, and slopes of maize and beans bleeding the land, water flocculated and purified, partly restoring its pristine purity, to blend with malt and yeast and hops on the shore of Lake Kivu. I tasted watersheds reaching and branching as they move upstream, penetrating the mountain uplands with their wet fingers, gathering the waters into the main stream. Water, gathering all of our decisions and actions together in one flow, one taste. The hope of it all lies upstream, in the Forest of Hope.

Related links:

- Brailirwa Brewery

- Forest of Hope Association

- Gishwati Forest Chimpanzees study by Chancellor et al., 2012

- Pfunda Tea Estate

- Rwanda Environmental Threats and Opportunities Assessment 2014

- ECODIT

December 24, 2014 4:37 pm

I noticed the tea is planted on the contour of the land. This reminds me of Hugh Bennett and Aldo Leopold’s efforts to get the farmers in the Driftless area of Wisconsin to plant along contours instead of up and down the hills. This was in the late 1930’s. See Bennett, H.H., 1939, Soil Conservation. MeGraw-Hill. Next time you’re at our farm I’ll show you some of the stream levees on small streams on our property that must have formed in the pre-contour farming time.

I enjoy your text and photos.

Dewey