July 2013. I’ve always loved the look of arums, those lovely flowers of the family Araceae, with their hoods and stalks, spathes and spadixes. Many people are familiar with them because of the common indoor plantings of “peace lilies,” various species of the genus Spathiphllum. Or from callas, often planted in gardens. Picture white, tame, pretty, pure.

La Virgen de Guadalupe with offering of callas on the road to the monarch butterfly reserve, Angangueo, Michoacán, Mexico, in 2004

But right now, in the heat of summer, Washington is gaga over a giant arum at the other end of the spectrum. Picture purple, pleated folds wrapped around a giant green… er… stalk. A titan arum, the biggest flower in the world, is blooming right now at the U.S. Botanic Garden Conservatory, in the shadow of the nation’s capitol in the nation’s capital. Scientific name: Amorphophallus titanum. Translation: giant formless phallus. You get the… er… picture?

Titan arum at the U.S. Bontanic Garden Conservatory on July 22nd, 2013

This particular flower just opened over the weekend, his/her behavior broadcast live 24/7 by streaming webcam, stoking the prurient interest of a host of Washintonian botanophiles, who turned out today to form a humid line that wrapped a block around the normally sparsely attended Conservatory. I say his/her deliberately, because most Araceae are monoecious, “the organs or flowers of both sexes borne on a single plant.” Yes, I was in that line. It wasn’t so bad, there was a bit of a breeze, a bit of shade. It was worth the wait.

Wow!

Titan arum

I first saw wild arums in Oregon during the spring vacation of my first year in college. Hunkered in the rain in my uncle’s cabin at Cannon Beach for days, when the sun finally broke out I wandered into the wet woods back of the beach, slipping and climbing over moss-covered logs to photograph Lysichiton americanus, the western skunk cabbage. Leaves a bit like cabbage, yes; smell like a skunk? No, not really. I was enchanted by the delicate knobby stalks standing in translucent yellow alcoves that seemed somehow protective. My fondness for arums began then. I guess you could call it Araceaeophily, but don’t try to pronounce that at home.

Western skunk cabbage, Cannon Beach, Oregon, April 1970

Western skunk cabbage, Cannon Beach, Oregon, May 2009

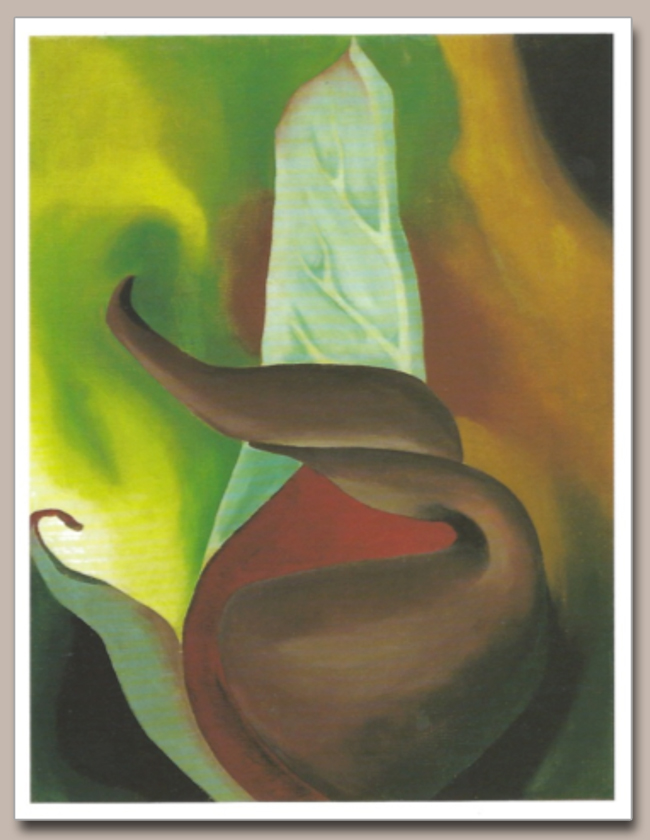

I became familiar with California-based Imogen Cunningham’s sensual black and whites of callas a bit later in my college days, and tried to copy them when I found a wild garden full at an old farmhouse on the coast south of San Francisco. The calla, often called “calla lily,” Zantedeschia aethiopica, is an arum native to southern Africa that became all the rage in American gardens when it was introduced in the late 1800s. Later I learned that Georgia O’Keeffe loved callas too, and gave them her own signature treatment, exploring their suggestive shapes, shades, curves, and depths.

Callas, Cannon Beach, Oregon, June 2010 (with a bow to Imogen Cunningham)

The stalk-like flower of the typical arum is called the “spadix,” and has both male pollen-bearing parts and pollen-receiving female parts. It is usually surrounded, protected, or enclosed by a modified leaf called a “spathe.” Besides their typical spathe-and-spadix structure, the Araceae have two other characteristics. They are usually pollinated by flies or beetles that they attract with scents that are often described as putrid, rotten, or skunky. The arums ain’t your “smelling like a rose” flowers. In the sticky afternoon heat of the Conservatory, a potent smell would sometimes waft over the crowd, causing a range of reactions from “uwww!” to “did you smell that?” It was strong, but somehow vague, maybe something a bit rotten, or at least something you wouldn’t want to smell too much or too long.

Arums are also often “thermogenic,” or heat-producing. The can expend stored energy to heat themselves up much warmer than the surrounding environment – a characteristic we usually associate with warm-blooded animals, not plants. There are two reasons proposed for this heat production. One is to attract insects, which as “cold-blooded” animals may be attracted to warm places. The heat is also thought to volatilize the the strong scent compounds that attract flies and carrion beetles as pollinators. Another function of this ability to produce metabolic heat may be to allow arums to emerge and bloom very early in the season. I’ve seen eastern skunk cabbage poking up through holes they have melted through a crust of snow and ice in late February or early March.

Mizubashō, Asian skunk cabbage, Abashiri, Hokkaido, Japan, May 1974

After college, travelling in the spring to Hokkaido, the northern island of Japan, I happened upon the peak bloom of “mizubashō,” Lysichiton camtschatcensis, the Asian sister species of the western skunk cabbage I’d seen in Oregon. In the soggy spring woods near Abashiri, looking across to the snowcapped volcanoes of the Kuril Islands, the Asian skunk cabbage filled the still-leafless woods with its pure white blooms. In Japanese, mizubashō means “water banana” – more poetic than “skunk cabbage.” Leaves unfurling like a banana, yes; growing in wet, flooded woods, yes. I couldn’t help associating these blossoms with the statues of Kannon Bosatsu that I had seen not long before at Zuiganji Temple, the spadix Goddess of Compassion standing under a protective, karmic spathe.

Kannon Bosatsu, Zuiganji Temple, Matsushima, Japan, May 1974

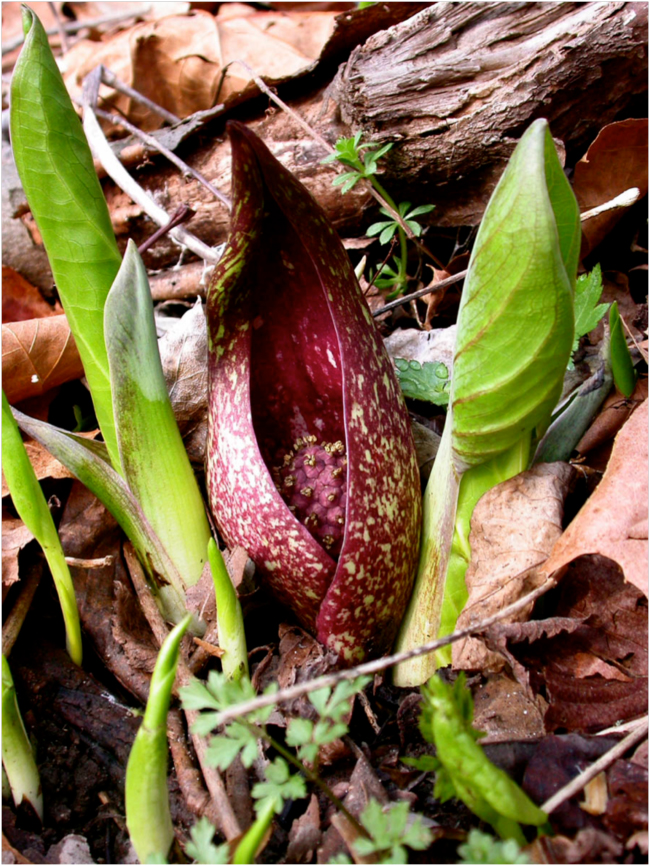

It wasn’t until I moved to the eastern U.S. that I saw eastern skunk cabbage, Symplocarpus foetidus. This species was more on the prurient and less on the pure side of the arum spectrum. Purple, contorted, obscure, yes. More in league with the titan arum than the calla, peace lily, and western and Asian skunk cabbages. Then I saw Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings of the eastern skunk cabbage, and realized she understood this yin-yang polarity of the arum family well. Her paintings of this species seem to lure us into the twisted labyrinth of the flower, and of desire itself.

Eastern skunk cabbage, Symplocarpus foetidus

In the shadow of the spatheless white spadix of the capitol dome, hundreds of people stood in line in the heat to get into the even hotter and more humid Conservatory to see that titanic stalk and skirt, the world’s biggest flower. Tourists, government workers, congressional interns, kids, couples, classes, and hey… wasn’t that Senator… ?

U.S. Botanic Garden Conservatory and the Capitol

Admiring the titan

Why? The looks of wonder and smiles of surprise showed that everyone here felt the fascination of something bigger, deeper, beyond us. Maybe they felt that this giant flower is a symbol of the vibrancy of life, the hope that hangs in the balance of the dance of death and desire. Or maybe that’s just my interpretation, the view of a self-confessed lover of arums.

See More Photos

Related Links:

July 26, 2013 3:30 pm

Bruce,

Beautiful photos — but I’m surprised that you’ve missed a photo of our Virginia native, jack -in-the-pulpit. They’re fairly common — and, there’s a nice sized grove of them in Mason Neck State Park in Lorton. I’ll take a photo next time (probably the spring) that I see one and send it along.

Best,

Rich

July 27, 2013 5:20 pm

Ah yes, jack-in-the-pulpit! I enjoy them too, in our early spring woods around here. Maybe next spring we can organize an expedition of our local arum-loving friends to visit the jack-in-the-pulpit “grove” you know about!

July 28, 2013 7:56 pm

Great blog! Wish I could see this plant, but alas, I’m in the Pacific Northwest in Sequim, WA. I moved here from SW Florida last September. We have some nice arums there as well. Thanks to R M Pyle for alerting me to your great blog. BTW, check out the giant stinky flower in the Rafflesia genus, named after the famous Raffles Hotel in I believe Singapore. Thanks again.

July 30, 2013 11:26 pm

I’m glad you enjoyed the blog, and thanks for the feedback! In our Washington, DC, muggy summer heat, I envy the fresh climate you must have in Sequim, Washington, in the rainshadow of the Olympic Mountains. I’m sure you can enjoy the western skunk cabbage blooming in the Sequim spring. Bob Pyle also called my attention to Rafflesia as a potential rival for the “world’s biggest flower.” Do you have a source for the claim that the genus was named after the old famous Singapore Hotel? That would certainly be an interesting bit of botanical trivia!

July 30, 2013 11:28 pm

A biologist friend, Robert Michael Pyle, pointed out in an email that I may have erred in calling the titan arum the “world’s largest flower.” He called my attention to the claim that Rafflesia arnoldii has the world’s largest single flower. According to “Everyday Mysteries: Fun Science Facts from the Library of Congress, “The flower with the world’s largest bloom is the Rafflesia arnoldii. This rare flower is found in the rainforests of Indonesia. It can grow to be 3 feet across and weigh up to 15 pounds! It is a parasitic plant, with no visible leaves, roots, or stem. Technically, the Titan arum is not a single flower. It is a cluster of many tiny flowers, called an inflorescence. The Titan arum has the largest unbranched inflorescence of all flowering plants. The plant can reach heights of 7 to 12 feet and weigh as much as 170 pounds!” http://www.loc.gov/rr/scitech/mysteries/flower.html

Of course, what we call the “flowers” of sunflowers, daisies, asters, and a host of other familiar plants in the family Asteraceae, are really composites of many tiny flowers. A sunflower is really an inflorescence, like the spadix of an arum. You be the judge, but ignoring the botanical technicalities, I still want to call both of them “flowers,” and still want to make the claim that I saw the world’s biggest. Of course, I’d love to see a Rafflesia arnoldii some day!